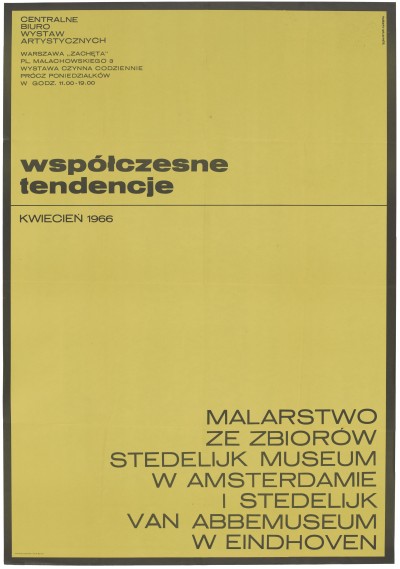

Contemporary trends Paintings from the collection of Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven

05.04 – 24.04.1966 Contemporary trends Paintings from the collection of Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven

Zachęta Central Bureau of Art Exhibitions (CBWA)

curator: Edy de Wilde

poster design: Hubert Hilscher

attendance: 10,839 (84 trips)

The author of the concept for the Contemporary Trends. Paintings from the Collections of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and the Stedelijk van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven exhibition, and its initiator, was Edy de Wilde (1919–2005).[1] The opinions of this charismatic museologist left their mark on the character of the whole exhibition. De Wilde was the director of the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven (1946–1963) and then of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam (1963–1985). Therefore, he presented works which he mostly bought for the museum collections himself.

Urszula Czartoryska wrote, ‘Personal responsibility taken by the director of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, E. L. de Wilde, means that he wanted, first, to clearly emphasise what he considered worth of “bias”, second, to enable the “competent” Polish audience to enter into a dialogue with him on matters that really require such a dialogue in Poland.’[2] The critic mentioned also that ‘the exhibition is addressed to the community, in which the organisers had done some prior exploration’. Therefore, visitors could see a display of works from the École de Paris, as Colourism is particularly popular in Poland, the works of the CoBrA group, aimed at those interested in expressionist figuration, Jean Dubuffet’s and Antoni Tàpies’ works for fans of matter painting and abstract expressionism, and the paintings of Victor Vasarely aimed at devotees of geometrical abstraction.

Considering that, it was a special exhibition compared to other travelling exhibitions venturing into the Polish People’s Republic, not necessarily profiled for the interests of the Polish audience. In the introduction to the exhibition catalogue, Edy de Wilde recalled the preparations, ‘A year ago, I visited Poland. I remember how touched I was by the warm welcome from the representatives of the Ministry of Culture and Art, how friendly my Polish colleagues and the most hospitable of all hosts, Professor Lorentz, were. I met with the Polish artists in the most cordial way. . . . I saw many studios and I found out how sincerely they cared about the Netherlands. I thought to myself then that it would be worth organising an exhibition that would certainly meet their interests. Nonetheless, as it is difficult to understand the development of Dutch art without educating oneself on its connections to foreign art, I proposed an international exhibition project, presenting modern trends in international art.’[3]

This carefully prepared review was fully appreciated only by Urszula Czartoryska, the author of the most extensive review and one of the few showing any indications of knowledge of the subject. Bożena Kowalska was not convinced about the coherence of the concept: ‘The exposition was a quite random collection. Something was missing. It had to be treated like a fascinating set of visiting cards of the most outstanding artistic personalities from all over the world, which could be extended by more than the same number of other names of equally interesting and famous artists.’[4]

An article by Jerzy Olkiewicz seems to be the answer to these accusations: ‘Only two of the displayed works were created before 1950. Judging from the character of the exhibition, it is no coincidence. On the contrary, it can be the key to understanding the sense of this, by no means chaotic, exhibition’.[5] Ewa Garztecka added that the show was ‘one of the most substantial of the post-war era’.[6] She wrote as well: ‘the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam is one of those which have the richest and most versatile collections of post-war art at their disposal.’ Henryk Andres also held the exhibition in high esteem, commenting that ‘the selection of exhibits, fragmentary by its very nature, and yet meticulously thought-out, illustrates the organisers concept very well, it seems’.[7]

A few years earlier, the Stedelijk had shared their collections with Poles as well. Between 1958 and 1959, an exhibition of 18 Dutch graphic designers took place (Kraków, Toruń, Lublin, Wrocław), organised by the Kraków branch of the Association of Art Historians and the Stedelijk (Dutch commissioner: J. van Loeben, Polish commissioner: Marek Rostworowski). Karel Appel’s, Corneille’s and Werkman’s pieces were found there. Besides, in 1960 the National Museum in Warsaw and the Management of Urban Museums in Amsterdam mounted an exhibition, which presented works by Vincent van Gogh, Appel, Vogenmauer and Corneille.[8]

At the opening of the event in Warsaw, the curator of the Contemporary Trends show, Edy de Wilde, mentioned that, ‘over the last five years, more was done in the field of art than in the previous fifteen’.[9] Czartoryska added in the review of the exhibition, ‘and yet he considered it necessary to present the achievements of the 1950s quite extensively, not to prove to us any “evolution” (he drew a clear dividing line between these two periods), but to indicate an important problem to Polish artists, who were moulded through the contact with the European art of the 1950s: how one can react to action painting or matter painting in the second half of the 1960s.’[10]

De Wilde studied law and painting. In 1946, he was appointed as director of the urban museum Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven. The institution was founded in 1936 with the private fund of a rich cigar producer and art collector, Henry van Abbe, who was interested in Dutch expressionism and magical realism.[11] De Wilde ignored the pre-war painting collection, which he found incomplete and of mediocre quality.

Since the 1940s, the museum had been associated with classic modernism and the contemporary avant-garde. De Wilde focused first on the Dutch art of that time and then on international art — it was the only way the museum could turn out to be outstanding in comparison with other Dutch museums. He introduced a quality standard — in 1951 he enriched the collection with the purchase of the painting Hommage à Apollinaire (1912) by Marc Chagall — one of the most important works by the artist and one of the most characteristic exhibits of the Van Abbemuseum. He also bought pieces by Wasilly Kandinsky, Oskar Kokoschka, Robert Delaunay, Piet Mondrian and Georges Braque. One of controversial purchases was Femme en vert, a very expensive 1909 painting by Pablo Picasso. French painting was de Wilde’s great passion and that is why he also acquired paintings by artists from the École de Paris. Subsequently, he purchased pieces of artists working outside of Paris: Asger Jorn, Antoni Saura, Hans Hartung, Pierre Alechinsky, representatives of artistic expressionism, Jean Dubuffet’s paintings and pieces of the Dutch group CoBrA. At the end of his term of office in Eindhoven, he organised two exhibitions presenting new phenomena in Paris and London, namely Compass I in 1961 and Compass II in 1962.[12] In 1963 Edy de Wilde, who transformed the Van Abbemuseum from a provincial centre into one of the most significant Dutch museums, was nominated to the position of director of the Stedelijk in Amsterdam.[13]

De Wilde’s predecessor in Amsterdam was Willem Sandberg, another charismatic figure of Dutch artistic life. After the Second World War, the museum achieved fame as a world centre of the avant-garde — the newest trends in art were shown and 30–40 exhibitions a year were arranged there.[14] In 1949, Sandberg organised the first museum exhibition of the CoBrA group, whose works he subsequently purchased for the collections. He also bought a selection of paintings by Kazimierz Malewicz and German expressionists. When he retired in 1962, a group of artists, including Wojciech Fangor and Tadeusz Brzozowski, gave their works to the Stedelijk as a gift. It is worth mentioning that, with Sandberg as director, the Stedelijk showed a travelling exhibition of Polish folk art in 1949 and displayed contemporary Polish painting in 1959 (15 artists, commissioner: Bohdan Urbanowicz; the exhibition design by Wojciech Fangor and Stanisław Zamecznik was highly appreciated[15]). Also in 1959, the Stedelijk hosted an exhibition of European ‘primitives’, during which four rooms were dedicated to Nikifor.

When de Wilde took the position of director of the Stedelijk in Amsterdam, he planned to keep the pace of 30–40 expositions a year.[16] While Sandberg treated the museum as a centre of current art and the collections were of lesser importance to him, de Wilde was first and foremost a collector.[17] He believed that having one’s own collections was less expensive than borrowing works. Moreover, as he claimed, collections express private views on art and include high quality pieces. Quality was crucial in de Wilde’s opinion. In a conversation, he stated that he had two possibilities in Amsterdam: either buying expensive cubist works (to make Malewicz better understood within the collection) or focusing on contemporary art. He chose the latter option.

Sandberg followed the model of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. His ambition was to present all artistic domains in the central, Bauhaus perspective (design, architecture and sculpture, all connected to each other). He is known to have visited Bauhaus in the 1920s. Sandberg perceived the museum as a mediator between art and society, for which he was criticised by the conservative part of society, which regarded him as a communist.[18] This idea did not speak to de Wilde, who did not adopt a theoretical, historical-cultural attitude. For him, visual quality was more important.[19] He purchased such works that could be representative for the whole body of work of a given artist, or even the whole body of work of an artistic movement. He believed that it was better to buy one good piece than a selection of only mediocre ones.[20]

The title of de Wilde’s show at Zachęta CBWA reflects the policy he established towards the collections. The contemporary trends were shown on a regular basis at the Stedelijk, for example: American Pop Art in 1964, Zero 1965 in 1965, Hard Edge and Colour Field Painting in 1966. The exhibition in Warsaw was divided into the following sections: École de Paris, CoBrA and its continuators, action painting, matter painting, Zero and pop art.

The first section of the exhibition was dedicated to the artists from the School of Paris. De Wilde had grand passion for French painting. While working in Eindhoven, he bought the paintings of Jean Bazaine, Roger Bissièr and Serge Poliakoff.[21] They were shown in Warsaw together with the painting of Maria Helena Vieira da Silva. Wim Beeren described the post-war work of the École de Paris in the catalogue for the exhibition: ‘Their modernity is unquestionable, manifesting itself, however, mostly in a characteristic interpretation of avant-garde works’.[22] He also added, ‘The style of the post-war École de Paris is marked by colour lyrics, omitting the theme or three-dimensionality. Their place was taken by abstraction, in which imagination is merely a starting point.’[23]

The second section of the exhibition in Warsaw showed the art of the CoBrA group and its continuators. The Stedelijk in Amsterdam boasts the most remarkable collection of the works by CoBrA members.[24] The name comes from the first letters of the cities: Copenhagen, Brussels and Amsterdam (there were a few Danes, Belgians and Dutchmen in the group, who were joined later by some French, Czech, German and American artists). It was coined in November 1948 by a Belgian writer, Christian Dotremont (he was, next to painter Asger Jorn, a key member of the group) as the title of a magazine popularising Dutch and Belgian experimental art and revolutionary surrealism. A large number of left-wing artists who were focused on radical experiments in art and literature became involved in the CoBrA movement.

The art of CoBrA was defined by primitivism, anti-intellectualism and the desire to escape the heritage of European culture. The members derived inspiration from old folk art, art of children or mental patients. The art of Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky and Joan Miró was also important for them. They were disappointed with civilisation that let the tragedy of Second World War happen. As Karel Appel put it, ‘I paint like a barbarian in these barbaric times.’[25] The CoBrA artists desired spontaneity and direct work, which led to certain austerity — their paintings seem unfinished. Moreover, they had much in common with abstract expressionism — both tendencies emphasised the belief that art stemmed from unconsciousness.[26] At the same time the artists used simplified figuration — thus they were close to the primitivising art of Jean Dubuffet. The 1922 book Bildnerei der Geisteskanken by Hans Prinzkorn, previously popular earlier among surrealists, was important to the CoBrA participants, just as to Dubuffet.[27]

Asger Jorn, Constant, Corneille and Karel Appel became acquainted with the collection of Dubuffet’s art brut in 1949, during the exhibition in the Parisian gallery René Drouin. However, CoBrA focused on collective projects and spontaneous art, while Dubuffet’s art was defined by loneliness and pessimism.[28] Beeren wrote, ‘The fact that all CoBrA artists used the same pictorial language was not only obvious, but also intentional — it meant negating particularism. Art is neither a specialisation nor a genius monster.’[29] Beeren also analysed the influence of the CoBrA group on other artists: ‘CoBrA was officially disbanded in 1951, yet its style still significantly affects the work of Lucebert or Alechinsky. CoBrA’s trends also inspired the artistic development of Appel and Corneille, who nevertheless, worked their way to their own, distinctive means of expression’.[30] The section of the exhibition dedicated to CoBrA, apart from the aforementioned artists, included the works by the following painters as well: Eugène Brands (self-taught), Jef Diederen, Lucebert and Jaap Nanning.

Another section of the CBWA exhibition showed action painting. American art had its first serious contribution to international art in the 1950s. 1950 was the key year, when Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning (Dutch-born), Arshile Gorky and four other artists represented American art at the Biennale in Venice. American art started to be described as savage, masculine and tragic, while European art as tasteful and literary.[31] In 1958, the New American Painting exhibition was organised, which visited six European museums, including the Stedelijk. At the same time, Jackson Pollock’s retrospective was travelling around Europe. Sandberg was not interested in American art and it appeared for the first time in the Stedelijk in 1964, when de Wilde was its director. It should be mentioned that in the 1950s, Peggy Guggenheim, a former museum dealer, gifted two Pollock paintings to the Stedelijk.[32] The Amsterdam museum was considered a ‘transitional’ point for art from the States in Western Europe.[33]

Waterbull (1945), a Pollock painting owned by the Stedelijk since 1950, was sent to Warsaw. The work constituted the artist’s answer to Picasso’s Guernica, travelling around the US from 1939 (kept almost constantly in the Museum of Modern Art in New York till 1981). American artists, not only Pollock, were fascinated with the enormous size of the Spanish artist’s canvas, its message and anti-academic character. Pollock’s work is an abstract, energising field.[34] The influence of Wassily Kandinsky’s pictures from 1911–1913 can be found in the painting. Previous canvases by Pollock were symbolic and primitive, while this painting shows his transition to a lyrical interest in nature.[35] Beeren noted, in the catalogue to the Warsaw exhibition, that it was Pollock who drew ‘the furthest consequences from abstract expressionism’.[36]

Urszula Czartoryska emphasised the meaning of Pollock’s art for Polish artists: ‘Jackson Pollock has his own legend and high standing in Poland, probably reinforced by Tadeusz Kantor, Jerzy Kujawski and a few other painters.’ She also wrote about ‘the awareness about his work in our country, so far away from the state of New York, where he lived and died’. She saw analogies of his art to the works of the artists from the 1st Exhibition of Modern Art in Kraków in 1948, admitting, however, that their art was influenced by Witkacy. Henry Anders added, ‘How distant, remote and majestically outdated it is today! What have the students of the wizard, countless imitators of that shaman, prophet and luminary from only twenty years ago brought about!’[37] De Kooning was represented with a piece from recent years (he was mostly known for his paintings of monstrous women of the 1950s), which Czartoryska placed at the ‘period of calmness’, ‘colour sensitivity “of the dawn”’.[38] Beeren concluded, ‘he painted figures of women of enormous dimensions, who drew their sexuality straight from an advertising poster and in this respect he could be labelled a forefather of pop art.’[39]

Bram van Velde was included in the action painting section of the exhibition at the CBWA. Beeren explained that as follows: ‘At the time when CoBrA still existed, first attempts of searching for a connection between the physical activity of painting and the character of its artistic result could be seen. Bram van Velde, who might possibly be seen as a member of the École de Paris, shows clear tendencies in this direction’.[40] Apart from that, the works by Sam Francis and the Spaniard Antonio Saura were presented.

Matter painting, which, as emphasised by Beeren, ‘was the most successful in the years 1950–1960’,[41] formed a crucial section of the exhibition. The most important person in this part was Dubuffet, who went into art when he was forty years old and who had previously been a wine dealer (he had inherited the company from his father). He was an outsider fighting with the mainstream avant-garde, not only an artist, but also a collector of art brut and an art theoretician.[42] Dubuffet’s art proved deeply significant to the Dutch in 1940–1960, especially for the CoBrA group. Dubuffet also influenced abstract expressionism by his cultural criticism and interest in everyday materials. The first exhibition of Jean Dubuffet’s works was organised at the Stedelijk in 1964 and a retrospective was staged two years later (the artist gave the museum in Amsterdam five of his paintings as a gift). Edy de Wilde met Dubuffet in the years 1955–1956 and bought his works for the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven. Dubuffet’s pieces from the 1950s, which are a part of Stedelijk’s collections, fluctuate between figuration and abstraction and aim at primitivising the reality.

In Poland, Dubuffet was shown as ‘a poet and master of matter’.[43] Czartoryska wrote, ‘but we missed the opportunity to show him as a human . . . who senses, in such an overpowering way, the absurd of civilisation (in paintings of as if cities with countless signs, cars and pedestrians).’ All critics complained that the real Dubuffet was not presented. Also the works by Antonio Tapies and Jaap Wagemaker could be found in the section of matter painting.

In the next section of the CBWA exposition, the pieces by Zero representatives were gathered (groups such as Zero in Germany and Nul in the Netherlands were formed in the second half of the 1960s). The artists of the new movement suggested that art should express the entire human experience. They used light, movement, space and time in their works. Beeren described the trend as follows: ‘Considering themselves citizens of the modern world, they separate themselves from the products of previous eras and they search for current structures. As they are fascinated by the dynamics of the present, they desire matter in motion and action. And since sentimentalism today is considered outdated, they confront impulsive psychic with indifference.’[44] He also added that the activity of an artist from this circle ‘does not resemble physical efforts of a craftsman, but rather the work of a film director or an engineer’.[45] One of the most significant achievements of the group was monochromatic painting.[46] A representative of this movement was Yves Klein, whose post-mortem exhibition took place at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 1965. According to Czartoryska, it was a turning point ‘in the proper evaluation of the artist’s output’.[47] Klein’s paintings, in her opinion, were able to reveal the essence of his work, which transcended painting. Other critics emphasised that too. Anders added, ‘the revolutionary, weirdo and storyteller in one, Klein once organised an exhibition which consisted of his welcoming the audience in an empty room’.[48] The show also presented the pieces by Enrico Castellani, Lucio Fontana, Otto Piene, Jan J. Schoonhoven and Victor Vasarely.

The last section of the Warsaw show was dedicated to pop art, excluding other movements emerging in the 1960s. Edy de Wilde did not appreciate minimal art, even though he was enthusiastic about the majority of the American avant-garde trends. He preferred pop art and colour field painting and for this reason, he mainly bought the works by Roy Lichtenstein and Barnett Newman.[49] After Second World War, mass production in the US developed on an unprecedentedly large scale and consumerism dominated culture. The pop art movement abandoned the concept of artistic originality and focused on mechanical production. Abundance and accessibility of goods were to show the advantage of capitalism over communism. In such works consumerism is in the foreground and humanity is less important.[50]

Among the representatives of pop art shown in Warsaw was Martial Raysse. As Czartoryska wrote, the exhibition organised earlier at the Stedelijk ‘opened his way to participate as a part of the French representation in the Biennale in Venice’.[51] The artist was named ‘the Matisse of our era’ by Pierre Restany. Because of some technical problems it was impossible to complete his works with neons and plants in Warsaw, and that is also why the pop-art installations and assemblages by Rauschenberg, widely represented at the Stedelijk, were not brought to the exhibition. Beeren emphasised that, ‘Pop art is an American and English phenomenon, while some related movements have been created in France and their most representative figure is Martial Raysse’.[52] For another artist of pop art, James Rosenquist, as Czartoryska wrote, ‘the technique of poster painting is an essential matter and the picture brought to Warsaw actually boils down to it’.[53] The pop art section was rounded out with the works by Jim Dine, R. B. Kitaj and Roy Lichtenstein.

Polish reviewers regarded pop art very critically. Actually, they felt mostly hopeless when confronted with it. Jerzy Madeyski stated that, ‘it is a problem more sociological than artistic’[54] and that ‘pop art is for us, who are far from flamboyant advertisement and fascination with the modern life in big cities, rather incomprehensible art (?)’. Also other critics did not recognise the value of the artistic phenomenon created across the ocean. Andrzej Krauze wrote the following about the pop art works: ‘What are those works worth? I guess they are only created so that future generations will be able to answer the question “what they were doing?”’.[55] Hanna Szczypińska added, ‘I could not resist the simple feeling that the works should be taken with a pinch of salt, treated as a joke or harmless perversion’.[56] Henryk Anders went even further with his opinion: ‘After us, the flood. And we are flooded with pop art.’[57] The critic wrote, ‘The error of pop art is not that it lacks content or idea, but that the content is trivial, although aggressive, and the ideology is vulgar.’[58] Ewa Garztecka described pop art in the most sensible way: ‘it would be pointless to assess pop art from the perspective of a traditional work of art, in isolation from the specific conditions of the North American big-city civilisation’.[59]

The exhibition occupied two rooms of Zachęta.[60] The Matejko Room was mostly filled with expressive abstracts. The other room was dedicated to pop art and the Zero group. Henryk Anders wrote about ‘the high quality of some works, meticulousness of their presentation almost resembling that of fancy goods, which is striking in comparison with the common Polish sloppiness.’[61] The designer of the exhibition was ‘an emissary of the museum in Amsterdam’.[62] The introductions to each section in the catalogue were written by Wim A.L. Beeren, the curator of the famous exhibition at the Stedelijk from the turning point between 1966 and 1967, namely New Shapes of Colour.[63]

Moreover, between 5 and 24 May 1966, an exhibition of Dutch graphic arts was organised at Zachęta by R. Hammacher van der Brande from the Boymans-van Beuningen Museum in Rotterdam. Edy de Wilde also worked on this event. Once again the works of the artists from the CoBrA group were shown. The press wrote that ‘The exhibition of contemporary Dutch graphic design, currently presented in the rooms of Zachęta, with more than 80 pieces of over 20 artists, is a continuation of the exhibition of painting from the Netherlands presented in April.’[64]

Polish art was also shown at the Stedelijk in Amsterdam. In 1969, there was the Perspectief in Textilen exhibition, in which Magdalena Abakanowicz and Wojciech Sadley, as well as Władysław Hasior, personally invited by de Wilde, participated. In 1972, concrete poetry by Stanisław Dróżdż was presented and the following year visitors could see the posters and graphics by Roman Cieślewicz. In 1978, the Polish Posters from Own Collections exhibition took place there (de Wilde was in the jury of the Poster Biennale at Zachęta in the same year).[65] In the years 1965–1970, a selection of Polish artists’ works, mostly posters, were purchased for the collections of the Stedelijk. The authors of the works included: Magdalena Abakanowicz, Roman Cieślewicz, Marek Freudenreich, Leszek Hołdanowicz, Jan Lenica, Zbigniew Makowski, Franciszek Starowieyski, Waldemar Świeży and Bronisław Zelek.

Edy de Wilde maintained his relations with the Polish artistic environment also after the end of the Contemporary Trends exhibition. In the 1970s, he corresponded with Piotr Krakowski and Witold Skulicz about the Print Biennial in Kraków[66], with Józef Mroszczak about the 4th International Poster Biennale at Zachęta[67] (de Wilde had to refuse being on the jury), with Hubert Hilscher about the 5th and the 6th Poster Biennale and with Waldemar Świeży about the 7th Poster Biennale.[68] The archives of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam also contain his correspondence with Ryszard Stanisławski about the plans of purchasing the works by Henryk Stażewski and Władysław Strzemiński for the Dutch collection.[69]

Karolina Zychowicz

Documentation Department of Zachęta — National Gallery of Art

This compilation was prepared as part of the National Programme for the Development of Humanities of the Polish Minister of Science and Higher Education — research project The History of Exhibitions at Zachęta — Central Bureau of Art Exhibitions in 1949–1970 (no. 0086/NPRH3/H11/82/2016) conducted by the Institute of Art History of the University of Warsaw in collaboration with Zachęta — National Gallery of Art.

Bibliography

Source texts:

- Anders, Henryk. ‘Współczesne tendencje w Zachęcie’. Przegląd Artystyczny, no. 5, 1966

- Beeren, W. A. L. Współczesne tendencje. Malarstwo ze zbiorów Stedelijk Museum w Amsterdamie i Stedelijk van Abbemuseum w Eindhoven, exh. cat. Warsaw: Centralne Biuro Wystaw Artystycznych, 1966, pp. 6–9

- B. O. W. ‘Współczesne tendencje’. Kierunki, no. 17, 1966

- Czartoryska, Urszula. ‘„Tendencje” muzeologów holenderskich’. Współczesność, no. 10, 1966

- Garztecka, Ewa. ‘Wystawa „ Współczesne tendencje”’. Trybuna Ludu, no. 98, 1966

- Grubert, Halina. ‘Kwietniowe wystawy w warszawskiej „Zachęcie”’. Express Wieczorny, no. 94, 1966

- Kowalska, Bożena. ‘Warszawskie wystawy’. Stolica, no. 26, 1966

- Krauze, A. ‘Tendencje 66’. Wiedza i Życie, 1966

- Madeyski, Jerzy. ‘Współczesne tendencje’. Życie Literackie, no. 21, 1966

- Olkiewicz, Jerzy. ‘Współczesne tendencje’. Kultura, no. 17, 1966

- S. A. M. ‘„Współczesne tendencje” w Zachęcie’, Słowo Powszechne, no. 89, 1966

- Szczypińska, Hanna. ‘Współczesne tendencje w plastyce’. Tygodnik Powszechny, no. 25, 1966

- Toeplitz, Krzysztof T. ‘„ . . . Rzeczy tak proste . . .”’. Kultura, no. 18, 1966

- Walicki, Leszek. ‘Współczesność i wystawa okręgowa’. Gazeta Krakowska, no. 119, 1966

- Wieluński, Lech. ‘Do wyboru, do koloru’. Głos Pracy, 1966

- Witz, Ignacy. ‘W Zachęcie’. Życie Warszawy, no. 119, 1966

Press mentions:

- Dziennik Bałtycki, no. 81, 1966

- Gromada Rolnik Polski, no. 52, 1966

- Polska, no. 7, 1966

- Projekt, no. 3, 1966

- Słowo Powszechne, no. 77, 1966

- Tygodnik Kulturalny, no. 16, 1966

- Tygodnik Powszechny, no. 15/16, 1966

- Trybuna Ludu, no. 95, 1966

- Życie Literackie, no. 16, 1966

- Życie Warszawy, no. 81, 1966

Artists

- Pierre Alechinsky (1927), Karel Appel (1921–2006), Jean Bazaine [Jean-René Bazaine] (1904–2001), Roger Bissière (1886–1964), Eugène Brands (1913), Enrico Castellani (1930), Corneille [Corneille Guillaume Beverloo] (1922–2010), Jean Dubuffet (1901–1985), Lucio Fontana (1899–1968), Willem de Kooning (1904–1997), Jef Diederen (1920), Sam Francis (1923–1994), Asger Jorn [Asger Oluf Jorgensen] (1914–1973), Lucebert [Lubertus J. Swaanswijk] (1924–1994), Jaap Nanninga (1904–1962), Serge Poliakoff (1900–1969), Jackson Pollock (1912–1956), Antonio Saura (1930–1998), Antoni Tàpies (1923–2012), Maria Helena Vieira da Silva (1908–1992), Bram van Velde (1895–1981), Jaap Wagemaker (1906–1972)

[1]Cf. ‘Wilde, Edouard [Leon Louis], de “Edy”’, in Dictionary of Art Historians (website), https://dictionaryofarthistorians.org/wildee.htm (accessed 15 September 2017).

[2] Urszula Czartoryska, ‘„Tendencje” muzeologów holenderskich’, Współczesność, no. 10, 1966, p. 5.

[3] Edy de Wilde, [untitled — KZ], in Współczesne tendencje. Malarstwo ze zbiorów Stedelijk Museum w Amsterdamie i Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum w Eindhoven, exh. cat., Warsaw: Centralne Biuro Wystaw Artystycznych, 1966, n.pag. [p. 3].

[4] Bożena Kowalska, ‘Warszawskie wystawy’, Stolica, no. 26, 1966.

[5] Jerzy Olkiewicz, ‘Współczesne tendencje’, Kultura, no. 17, 1966.

[6] Ewa Garztecka, ‘Wystawa „Współczesne tendencje” (Kolekcja z holenderskich muzeów)’, Trybuna Ludu, no. 98, 1966.

[7] Henryk Anders, ‘Współczesne tendencje w Zachęcie’, Przegląd Artystyczny, no. 5, 1966, p. 11.

[8] Sztuka obca w Polsce 1945–1960, typescript, documentation department of Zachęta — National Gallery of Art.

[9] Czartoryska, p. 5.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Vanabbemuseum: A Companion to Modern and Contemporary Art, ed. Monique Verhulst, Eindhoven, 2002, p. 13.

[12] Ibid., p. 17.

[13] It is worth mentioning here that a travel exhibition of Polish tapestry was shown in Eindhoven in 1965 (commissioner: Ryszard Stanisławski).

[14] Sandberg organised individual exhibitions of such artists as: Pierre Bonnard, Alexander Calder, Le Corbusier, Marc Chagall, Naum Gabo, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Fernand Léger, Kazimierz Malewicz, Henry Moore, Pablo Picasso and Kurt Schwitters. Until 1972 (when the Van Gogh Museum was established next to the Stedelijk) a collection of Vincent van Gogh’s works had been kept in the museum in Amsterdam.

[15] Sztuka obca w Polsce 1945–1960.

[16] He organised retrospectives of Alexander Calder, Jean Dubuffet, Max Ernst, Lucio Fontana, Naum Gabo, Hans Hoffman, Willem de Kooning, Pablo Picasso, and young artists: Arman, Yves Klein, Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol. He also regularly exhibited works of Dutch artists.

[17] ‘20 Years as an Art Collector. An Interview with Edy de Wilde,’ in 20 Years of Art Collecting. Acquisitions Stedelijk Museum 1963–1984. Painting and Sculpture, ed. Joop M. Joosten, Amsterdam, 1984, p. 7.

[18] Jan van Andrichem, ‘Reflections’, in Stedelijk Collection Reflection, ed. Jan van Andrichem, Amsterdam, 2013, p. 30.

[19] ‘20 Years as an Art Collector . . .’, p. 13.

[20] Ibid., p. 14.

[21] Vanabbemuseum: A Companion to Modern and Contemporary Art, p. 16.

[22] W. A. L. Beerem, ‘Ecole de Paris’, in Współczesne tendencje . . ., n.pag.

[23] Ibid., n.pag.

[24] Colin Rhodes, ‘Cobra: Myth, Materialism, and Primitive Renewal’, in Stedelijk Collection Reflection, p. 267.

[25] Ibid., p. 267.

[26] Ibid., p. 270.

[27] Ibid., p. 274.

[28] Ibid., p. 271.

[29] W. A. L. Beerem, ‘Cobra i jej kontynuatorzy. Co-penhagen Br-ussel’, in Współczesne tendencje, n.pag.

[30] Ibid., n. pag.

[31] Jeremy Lewison, ‘Pollock, de Kooning, Guston. A European Heritage’, in Stedelijk Collection Reflection, p. 336.

[32] Ibid., p. 335.

[33] Van Andrichem, Reflections, p. 33. The first purchase of American art in Europe took place in 1959 (Basel and London).

[34] Fitzgerald, ‘The Next Half of the Century “Will be Ours”’, in Stedelijk Collection Reflection, p. 255.

[35] Lewison, p. 336.

Contemporary trends

Paintings from the collection of Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven

05.04 – 24.04.1966

Zachęta Central Bureau of Art Exhibitions (CBWA)

pl. Małachowskiego 3, 00-916 Warsaw

See on the map