Nr. 39

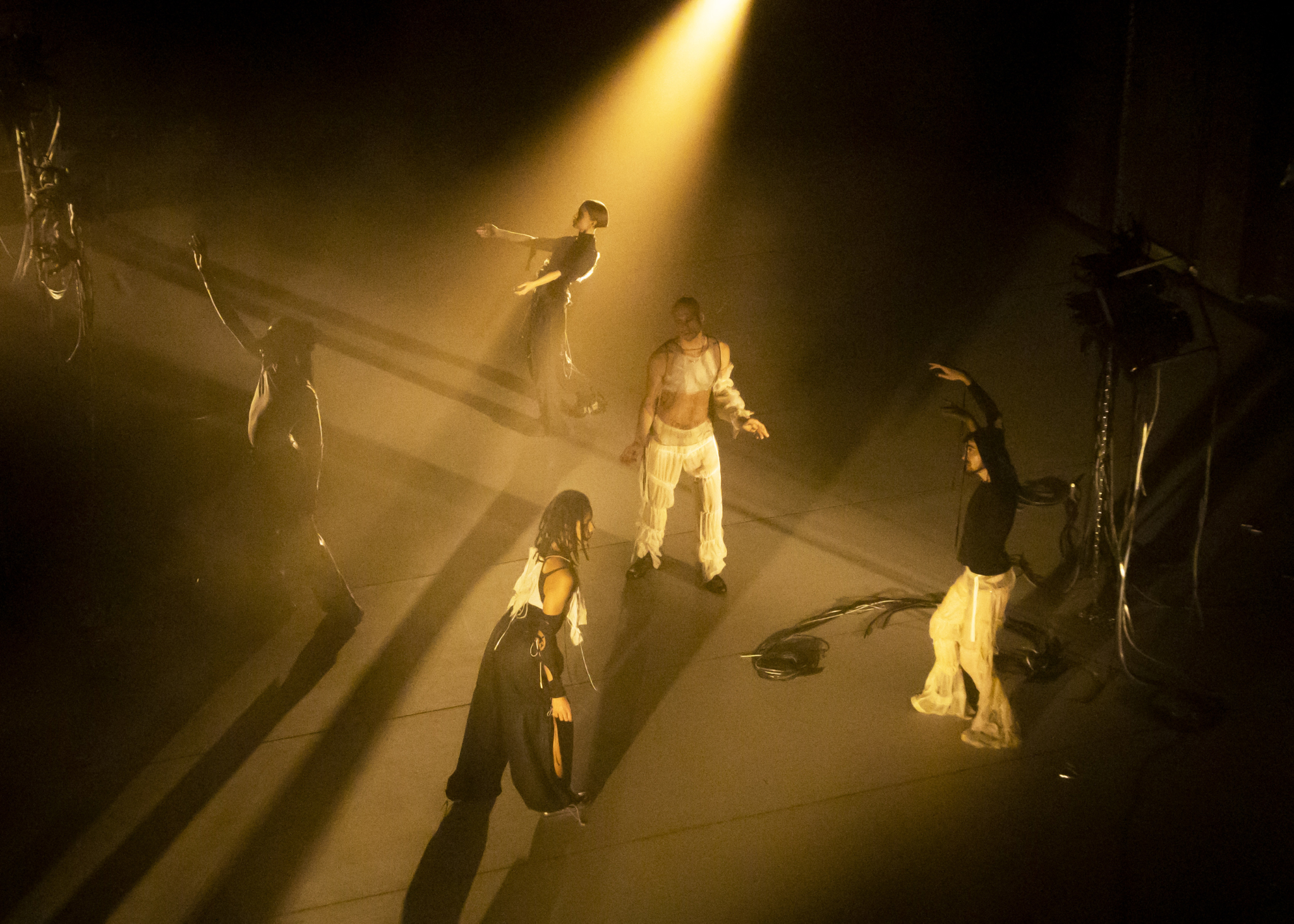

Embracing the Darkness, Leaping into the Unknown

Aleksandra Skowrońska and Michalina Sablik Discuss the Exhibitions From the Ashes and Does the Rising Sun Affright

15.04.2024

Michalina Sablik, Aleksandra Skowrońska

Aleksandra Skowrońska: An impulse, a diagnosis, several weeks of the most intense (collaborative) work I’ve ever undertaken, and here they are! On the 15th of March we opened two exhibitions in Zachęta: From the Ashes and Does the Rising Sun Affright. After the emotions of the opening have calmed down, we finally have the opportunity to look from a certain distance at both our own proposal and the one with which we are entering into dialogue through the tool of curatorial practice. How would you sum up these exhibitions after a while? Are they autonomous and separate, although they remain in a perceptible relationship?

Michalina Sablik: Both exhibitions arose from the realisation that we are going through a period of profound change in many areas – political, economic, environmental and technological. We are witnessing rapid transformations on a global scale due to the climate crisis, which is leading to civilisational change. They call for the formulation of new international strategies and, more importantly, a change in the way we think about the world, our place and the role of humanity, taking into account local contexts.

In recent years, we have seen the negative consequences of these changes, including wars, pandemics, increased social divisions, migration and a shift towards political radicalism. Times of upheaval and crisis often trigger a backlash and a return to familiar territory or old, tried and tested narratives and strategies. The programme of the former director of Zachęta here, on a local level, and the phenomenon of Trumpism on a global scale represent the last gasps of an outdated world that refuses to go away, clinging to an old order rooted in anthropocentrism and androcentrism. Zachęta and other public cultural institutions were supposed to be bastions of archaic ideologies.

AS: In fact, some of these institutions still cling to such principles. And it’s not limited to Poland or even Europe. I’m afraid that in the face of the multiple crises we will see a further spread of conservative attitudes, linked to the urge to return to familiar and safe diagnoses, traditions or models. This makes the two exhibitions all the more important as counterpoints or even propositions in the construction of (counter)narratives about the changes to come.

MS: These exhibitions suggest a different way of thinking about the role of art in diagnosing, critically commenting on reality and looking into the future. We are presenting art in search of new concepts and tools to name reality and to develop new narratives. This reminds me of Ursula K. Le Guin’s proposal to write new science fiction, that is, stories about living, gathering fruit and walking in the forest, rather than stories about hunting and killing – these ideas are echoed in Aleksandra Liput’s work.

AS: I’m glad you mentioned looking into the future. Joanna Erbel, author of Wychylone w przyszłość. Jak zmienić świat na lepsze [Leaning into the future. How to change the world for the better], talks about the need to test visions and dreams in practice, and about art, which has the power to sense what might happen in the near future. Art – among its many definitions – can become a means of communication in which sensitivity and analytical skills come together in a synergistic combination. This can produce an experience that speaks to us in a non-verbal way from an undefined future – whether speculative, near or distant, but anchored in the present.

MS: There is a need to develop new paradigms. But this requires the courage to face reality, to step into the darkness that Timothy Morton wrote about, or to take a leap into the unknown (Rebecca Solnit). Søren Kierkegaard described this moment as a ‘leap of faith’. Artists often feel the need to respond to reality. I think that as long as you have the right material conditions, you should have the courage to take a ‘leap of faith’, to try to change reality through action, but also to influence other people’s thinking about the world through art, activism or educational activities.

AS: Both exhibitions are based on such premises – although the postulatory nature of From the Ashes is rooted more deeply in current politics and encourages concrete action, while Does the Rising Sun Affright is focused more inwardly – on the urgent need to rethink general paradigms, fundamental concepts. What is important is that one cannot exist without the other; they are incomplete and flawed.

MS: In the case of From the Ashes, I use the metaphor of the mythical Phoenix to show transformation – the burning of the old world and the birth of a new one. The turning point is a time to reimagine this world anew – perhaps the Phoenix can and must be reborn in a different form. I am also interested in the perception that we got stuck in grand narratives, as if in a loop. Michael Marder, in his book The Phoenix Complex: A Philosophy of Nature aptly shows how limiting it can be to think of nature as a phoenix, assuming that because nature is cyclical it will always be reborn as the same thing. Apart from myths, we also have pop culture and internet images that define the horizon of our thinking about the future. Our ideas of the future are dominated by disaster or science fiction films, computer games, both utopian and dystopian, which have been produced in abundance recently.

AS: Yes, what’s particularly interesting here is the (counter)culture of the meme – fertile, uncensored, responsive to reality, not yet fully commodified or capitalised (although in this case I wouldn’t be asking ‘if’ but ‘when’ its full capitalist appropriation will inevitably occur). Its power lies precisely in its elusiveness, its ‘viral’ nature and its unpredictability, the quintessence of an experiment.

MS: That’s why From the Ashes begins with two works that comment on how we function in the media world. In her work on a cinematic scale, Sara Bezovšek compiles thousands of images of disasters to show the limiting potential of the doomscrolling that we practise every day. Meanwhile, Xtreme Girl uses the visual language of tech companies to outline the situation of functioning in a computerised reality, where the Internet once promised freedom and democratisation, but has become a system that controls almost all aspects of our lives. Innovations like bitcoins or social media were supposed to be tools for a better world.

AS: This only shows that new tools (but also new forms of expression, new forms of communication) do not provide solutions or remedies for the problems of the old order and systemic diseases. Left to their own devices, unintentionally released into space, they will sooner or later adapt to the prevailing conditions. It’s a bit like Catherine Malabou’s concept of plasticity (pejoratively understood as a warning) – the philosopher observes that all transformations only affect form, not essence. In this context, such a diagnosis borders on a kind of lazy nihilism, but well – we’re discussing crises, I think we can afford it (smiling).

But one can also draw conclusions that are less marked by apathy and more focused on – again – the future. After all, if we do not see the potential for change in the tools, then in what? The exhibition Does the Rising Sun Affright is an attempt to answer this question. Drawing on Morton’s philosophy, it is an invitation to think differently about the role of humans and their environment, while the works on display are points of contact, cracks through which such insight can be gained. It’s an invitation to open one’s sensibility to affective, aesthetic, embodied experiences (which in this context are most resonant in Hypercycle by Aleksandra Słyż, Hopecraft Ceremony by Natasza Gerlach, or the Inner Saboteur series by Claude Eigan), and an invitation to imagine another world – before that ‘other world’ even begins to emerge.

MS: All of this intersects with questions of generational experience – or rather entangled and overlapping experiences – because it’s hard to single out one defining event. Thinking in ‘generational’ terms is, in a sense, doomed from the outset because it implies simplification, narrowing and a lot of arbitrary decisions – what is part of the generational experience and what is already an individual experience? But given that the alternative would be to give ground to other, externally imposed narratives, this risk seems to be the only possible option.

AS: What effectively binds and connects the experience of the artists invited to co-create both exhibitions is that they function in suspension, in between. On the one hand, they reach back to the moment of coming of age at the end of the 20th century – with the history of the expansion of global capitalism and the birth of mass media culture. On the other hand, they mature and enter adulthood in the 21st century, at a time of intensification and acceleration of processes rooted in previous decades, against which contemporary politics seems – or seemed – unable to (counter)act. Incidentally, this is one of the main objections raised by Alex Williams and Nick Srnicek, who in the Accelerationist Manifesto point out that contemporary crises are gaining strength and momentum – while politics is weakening and slowing down. At the same time, we see the emergence of narratives of care and empathy – including planetary empathy towards non-human beings. Whether these narratives are authentic or merely declarative is another matter.

What is also striking, though not surprising, is the trend towards what I would call the materialist turn or the material turn – with full awareness of the multiple references that term entails. And this applies to both exhibitions – it manifests itself in the study of the material properties of reality, the questioning of binary categories (Tiziana Krüger, Bianca Hlywa, Hanna Antonsson), the move towards tactility (Cezary Poniatowski, Ania Bąk, Aleksandra Liput), and speculative practices (Julia Lohman, Inside Job). I think this is an inevitable consequence and response to the fatigue of functioning in the digital space, the ultimate backlash against naive catchphrases: the popular metaphor of the ‘global village’ and the belief in democratisation through the widespread use of network technologies, right through to the finale of this optimistic narrative – the disruption caused by the constant dopamine hunger of social media updates, or simply the fatigue of omnipresent screens. At the same time, observing (or rather: feeling, because I think the affective key to the reception of Does the Rising Sun Affright is the best reception strategy) from a certain distance, I can’t help but feel that the exhibition heralds what I would tentatively call the return of existential themes in the post-anthropocene context – another attempt to find the meaning of one’s own existence in the face of a changing understanding of the relationship between human beings and their environment, along with the simultaneous acceptance that we are still ‘becoming’ and remain in the continuous continuation and realisation of the project of ourselves. There are so many complex contexts here, not to mention the most recent, political and institutional!

MS: Whether we like it or not, our exhibitions have coincided with an important historical moment for Zachęta, which fits into a broader context of political change. I deliberately avoided works in the exhibition that directly commented on political reality, although I greatly appreciate the art of protest and activism that has erupted out of necessity in Poland in recent years. There are already many amazing people working at the grassroots level for women’s rights, ecology, migrants, a fairer distribution of resources or education. For me it was important to take a step further, towards speculation, fantasy, queer (the X-Philes collective) or hydrosexual (cyber_nymphs) utopias, which somewhat escape polarizing discourses.

AS: This narrative of crisis and attempts to overcome it coincided with a period of change within Zachęta itself that was eagerly anticipated by many, including Zachęta’s staff. This made the commitment of everyone involved in the two exhibition projects all the more palpable and moving. In this collaboration, it seems particularly important to move away from hierarchical, even post-serfdom, relationships towards models that recognise subjectivity and agency, and above all, unconditional respect for everyone involved in the process. This also ties in with the theme of both exhibitions, which propose democratic models of coexistence.

MS: This is especially important in the context of the last eight years, when the Polish art scene has been severely affected by a lack of adequate institutional support, access to grants or scholarships for project development, precarious working conditions, aggravated by the pandemic, the war in Ukraine, inflation, etc. However, I feel that the community has come out of this experience stronger, because it has developed new ways of working based on collaboration, participation in protests and aid activities. It also warmly welcomed migrant artists who brought their talents and different perspectives, such as decolonial ones. New artistic practices have always been present, but dispersed and in the underground, and now it is time for them to find their place in institutions like Zachęta.

Michalina Sablik (b. 1993) – art historian and curator. She graduated from the Interfaculty Individual Studies in the Humanities Programme, completed postgraduate studies in Cultural Diplomacy at the Jagiellonian University, and studied gender and postcolonial studies at the University of Utrecht. She is a PhD student at the Doctoral School of Humanities at the University of Warsaw. She has worked at the Galeria Promocyjna and the Old Town Cultural Centre in Warsaw, and at the Adam Mickiewicz Institute/Culture.pl. She has curated over 20 exhibitions and collaborates with numerous institutions, galleries, NGOs and art magazines. She is a member of AICA.

Aleksandra Skowrońska – PhD student at the Faculty of Anthropology and Cultural Studies at Adam Mickiewicz University (UAM) in Poznań and member of the Humanities/Art/Technology Research Center. She graduated from the Faculty of Polish Philology at the Jagiellonian University and also completed the Interfaculty Individual Humanities and Social Studies at the UAM. She has cooperated with cultural institutions, NGOs and research institutions such as Zachęta – National Gallery of Art; Pawilon, Poznań; Arsenal Municipal Gallery in Poznań; Malta Foundation; Time of Culture Association; Foundation of Cultural Education Ad Arte; Poznan Supercomputing and Networking Center; and Poznań Science and Technology Park. She programmes, curates and writes.