No. 36

The wheel of eternal return

Animations by Mariusz Wilczyński

23.03.2022

Adriana Prodeus

Where did the unfinished, sketchy, coarse form come from in Mariusz Wilczynski’s animations? Scribble-like, looped shapes whose lines are broken, tangled, and blurred. Their author likes to present this seemingly imperfect character of animation as the result of incompetence, the effect of attempts doomed in advance to suffer imperfection, and himself as a self-taught artist who achieves mastery almost by accident. However, the way the author’s animated films look owes not so much to the loose, pretextual style of his works, but to performance art that the artist has been practicing since the 1980s.

Before he came to be known as a member of the Light Open Society, a group with which he began his quest in the field of performance, Wilczyński graduated from Stanisław Fijałkowski’s painting studio at the Academy of Fine Arts in Łódź and stayed there for a few years as an assistant teacher. What did he take from the master of concise form and elementary graphic metaphor? At first glance, only a subdued, uniform low-temperature colour tone, glowing with a single element, as if opening a portal to another dimension. Apart from that, everything is different, as Wilczyński was quick to find his own idiom beyond painting. Avoiding categorical solutions in his compositions, he focused on detail and expanded the narrative aspect. He transformed the predilection for allusion and reflection on the form that Fijałkowski inherited from Władysław Strzemiński (whose student and assistant Fijałkowski was), into blunter symbolism, referring to figurative, fairy-tale, and thus universal imagination. The animator’s goal was to create a framework of meanings available to the widest possible audience. And it had occurred long before Kill It and Leave This Town (2020). After one showing of Wilczynski’s retrospective at the Perma Museum in Istanbul, a viewer confessed she felt like “a single tear in an ocean of sadness”. This is so as the poetics of these films appeals to the emotions of the audience. Cruelty, melancholy, and fragility of life are the themes most often discussed by the artist who seeks metaphysics only in the here and now.

Fascinated by Fijałkowski, the artist chose his own path, with his master’s modest, pared-down, ambiguous compositions remaining a point of reference for him however. This connection is provided by the mystical sphere, invisible on screen but clear in the self-commentary. In Fijałkowski’s work, it is based on ascetically geometric abstraction, but Wilczyński does not aspire to the strict discipline and modesty developed by the author of Talmudic studies. He touches on the subject of spirituality, but differently. The decision to keep the world of his animation to what is mundane, ordinary, and limited to the experience available to everyone has serious consequences, as contact with the absolute is possible only among the requisites of everyday life. At every step, the harmony of the world is established by virtue of matters of paramount importance: love, desire, friendship, but above all, by simply accompanying another being – both human and animal.

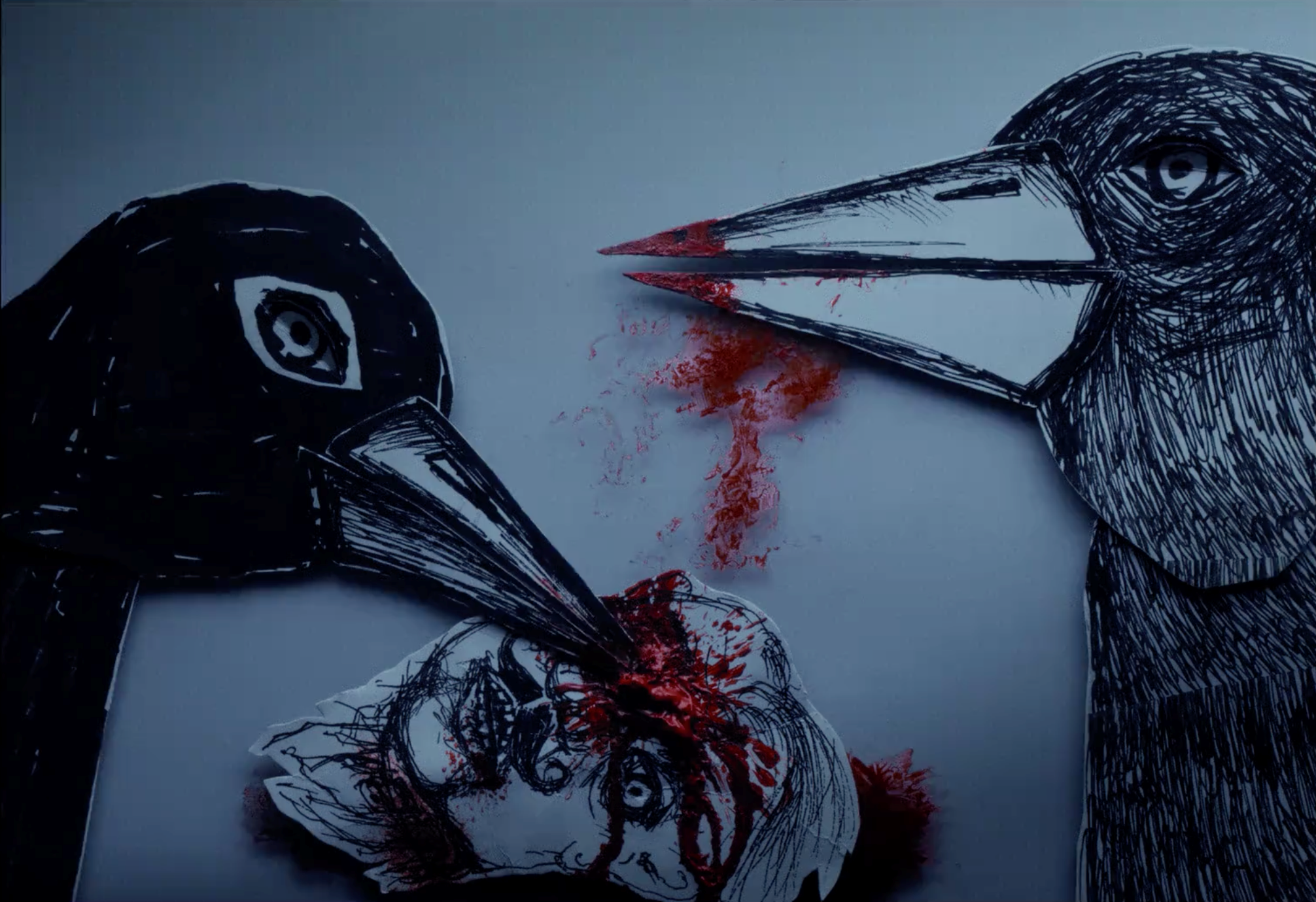

Wilczyński cooperated with the Light Open Society for a few years (1988–1992), doing performances to live music played by the Kormorany or Kinior together with Darek Fiet, Maciek Szewczyk and Mariusz Wolański. What they were doing could hardly be called live animation, it was more like a sequence of slides, often time-lapsed in spatial screens, made of multiple layers of curtains or other openwork materials forming rasters, filters, and masks. Photographed from different sides, the image was projected onto a kind of animation desk. Light and sound performances or rather “lighttoday” – as the creators called them – determined the modus operandi of Wilczyński’s art. To this day it has preserved, both in performances and in films, the atmosphere of the artist’s joint celebration with the musicians, and the clear gesture of revealing the artist’s technique by means of a small camera placed by an easel. Likewise, the collage-like, impermanent structure of sheets of paper – torn, perforated, destroyed during the performance, which Wilczyński, like an illusionist, “conjures up” with ordinary tools: black marker, paint, and scalpel. All this is supposed to serve a peculiar mystery of everyday life not unlike the one that was celebrated by Miron Białoszewski in the colander spoon seen as a monstrance (Grey eminences of delight). After all, the poet was known for his performances, about which his housekeeper used to say: “Hush, they’re officiating there” or “foretelling” as these events were something between prayers, sorcery, and rituals. In his performances, Wilczyński “foretells” life and death, confusion and understanding, smallness and greatness. He usually uses the same set of objects: house, bed, candle, fish, bird, dog, cat, king, old men, pair of lovers, infant, giant, and brains connected to apparatus. The cinema with its attributes also forms an integral part of the celebratory act. Cartoons, a beam of light from the projector, the audience enchanted by the screening create a frame for introspective references. Whenever the light goes out and a glowing, vibrating image emerges from the darkness, it becomes an act of creation, the only magic available.

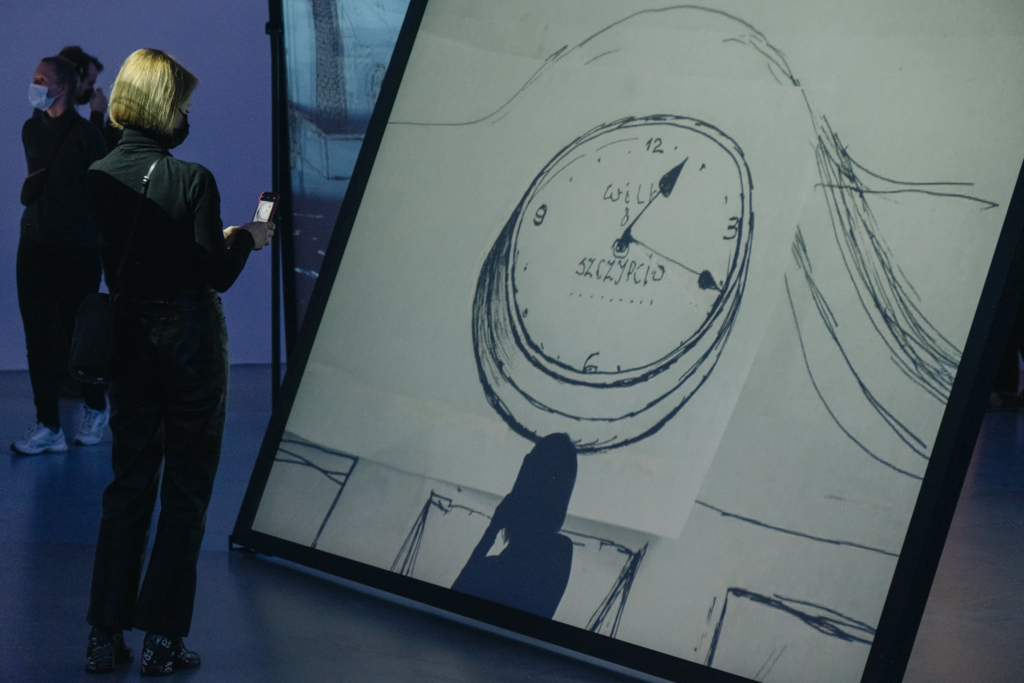

This is why Wilkanoc[i]performances, performed by the artist alone, in dialogue with a musician, an ensemble or an entire orchestra, form this kind of hastily created cinema, bringing back the spectacle of the cinematograph or even its alternative path – the magic lantern. It is about a proto-film night in which the stars are the first cinema. It has had many various manifestations: from Pol-Dives’ slide shows in Paris between 1935 and 1939, known as vitromagic, to contemporary experiments with analogue image and sound performed by the duo of Polish artists kinoMANUAL. Wilkanoc owes its special character to the fact that each time the artist mixes fragments of his films a little differently, improvising with jazz musicians. The style of the drawing created during the performance is therefore a visual response to the sound proposition. Different audio tracks add a new dimension to the same items arranged in a different order. Wilczyński treats himself as yet another instrumentalist, developing his part during rehearsals with musicians, using the available assortment of forms, creating variations around fixed themes. The performance gives the artist’s films a musical structure – repetitions, refrains, recurring motifs, around which a specific visual melody is based. Because it is not animations that provide illustration to music, they themselves become music and in this compositional way build their dramatic effect, which Jerzy Armata calls “animated blues”, although this features not only blues, but also other musical genres, from rock to Maurice Ravel’s Bolero.

Already Wilczyński’s first music video – Justice (1996) – to the song by the band Tie Break reveals his voracious appetite for experimentation with animation techniques. A lot is going on there, and it is difficult to keep up with the pace of change, which was typical of music videos of the 1990s, especially shown by the then popular MTV channel. The extraordinary pace and unfinished, excessive form also brings associations with the peak moment of the Polish systemic transformation, when progress was to be created by our own effort and the sudden acceleration of political change was supposed to satisfy the appetites that had built up over the years. The film is based on poetry, as Wilczyński made a series of Bookclips – short films inspired by literature – for the state television channel TVP in the 1990s. Father Jan Twardowski’s poem receives a multi-layer illustration here – it is animated with puppets, cut-outs, paintings, and drawings. But already at this stage, among many elements, there appears one that is characteristic for Wilczyński: a planet, like the one from Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s Little Prince, but with a house through the window of which enters the camera. Also typical of the artist’s later activities is the physical presence of his hand on the screen when, turning the pages, he activates his characters like a demiurge. The hand of an animator, a theme known from the history of the cinema, especially by virtue of Charles M. Jones’s Duck Amuck (1954), becomes Wilczyński’s favourite element – it reminds us that everything we see is drawn. The artist’s finger persistently trying to pierce a balloon with a drawing of a human face appears in the video clip I Hate (1999) by Agnieszka Chylińska with Laibach band. It turns into a fist with a knife that smashes the balloon into a bloody mess. It is difficult to determine who dictates the conditions here: the artist or the rebellious characters acting on their own behalf. The author also imprints his own likeness among them, often on multiple persons. So he is the “little man” in the middle of this “fairy tale”, and at the same time the perpetrator, responsible for the world created so imperfectly.

The music videos, which became an integral part of Wilkanoc performances as well as a direct prelude to autonomous films, evolve to become homogeneous. The artist broadens his drawing universe, from From the Green Hill (1999), illustrating the eponymous track from Tomasz Stańko’s album, to Death to five (2002) to Grzegorz Ciechowski’s last song, where he reduces the form to a minimum. The main role here is played by the looping of the wheel of living and dying, which stopped like a clock in which time never moves forward, even though the hands are moving around. Wilczyński also used this theme in his film Times Have Passed (1998) referring to Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times (1936). The style of the cartoon animation clearly condensed between his first collaboration with Tomasz Stańko to the last one, in the film Unfortunately (2004), to which the trumpeter recorded the score (originally the film was made as a video clip to a song by Kayah).

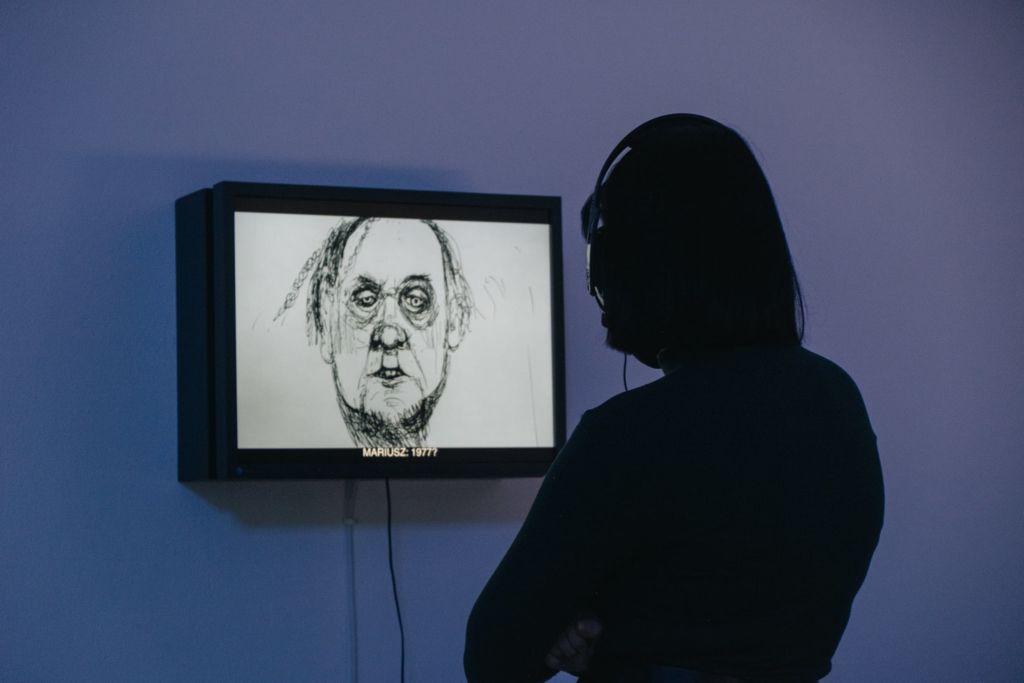

What defines the expression of Wilczyński’s characters is the line. The image vibrates with a trembling line and white noise on the screen achieved through the use of heavy grain paper or a sheet of graph paper as if torn out of a school exercise book. Sometimes a cut-out element appears, but only as another scrap of paper, a photo, a quote, which becomes an integral part of the collage. The portraits are becoming more and more granular and characteristic, which makes it easy to recognize the face of Stańko or Fryderyk Chopin in Chop, Chop, Chop, Chopin… (1999). This tendency will see its culmination in the characters from Kill It and Leave This Town that were drawn on the basis of pre-recorded voices of actors. It is then that Wilczyński begins to play with resemblance – of the female insurgent to Mickey Mouse, of the male insurgent to the stork-Donald Duck, of himself to his own caricature. His portraits are rooted in conventionality, creating an illusion that they were created hastily. Their form is open, although meticulous, evoking the past, still suspended in the communist era. Rather than adding more layers, the artist focuses on elimination. Immersion comes to the fore, a trance-like state of being irritated by memories and dreams, the mind escaping into further deliberations.

In Kill It and Leave This Town, a sound composition was first created, a kind of radio drama to which the director added a visual layer. Starting with Kizi Mizi (2007), Wilczyński treats music as a component of the sound fabric created together with Franciszek Kozłowski. There, he used the TVP Kultura channel’s signature jingle, which accompanied subsequent episodes of the animated setting, and incorporated it into the film as a repetitive unit, a refrain that adds rhythm to the monotonous life of a cat and mouse in a toxic relationship. Even though songs appear here – Need Your Love So Bad by Fleetwood Mac and Peter Green, and They’ll Come Right Here by Tadeusz Nalepa – this is the repetitive sound that dominates the image and sets the trajectory of the action: a tomcat jumping out of a clock or a train pulling into the final station. It was then that Wilczyński finally abandoned his practice of making films “to music”, to video clips and various kinds of illustrations to what is being played. From then on, the logic of the film as a holistic narrative has been of paramount importance in his work, and the artist himself has become the conductor of the whole, having at his disposal sound, pieces of music, and storytelling with images.

The variability of the frame – its size and shape – has also moved on with Kizi Mizi to his latest film. Wilczyński adjusts the screen format to the needs of a particular scene. He manipulates it by recalling historical media, focusing the viewer’s attention on a significant detail. As if the performance was not only about improvisation with musicians and ephemeral visual form, a cinematographer was also invited to be part of the ensemble. In the projection booth, recordings are being mixed and the beam of light is adjusted. This element of the rite of memory is necessary to experience it fully.

Actors and actresses, the artist himself, as well as splinters of his old films are evoked at a spiritualistic séance. Everything has a right to exist here: high and low, finished and implicit, infantile and erudite. Spirits lay on different layers of this space. Here is a bridge between Light Open Society’s performances of Lighttoday, cobbled together from what was readily available, and the way Wilczyński precisely and painstakingly builds his film world today. Memory spins around and repeats in a variable form an infinite number of times. Time is cyclical, we study its pulse without an initial or final state. There are many options, but limited in number, so they eventually return in some form. Underlying the mystery is also the knowledge of the constant elements of the rite.

As the lights go out, the curtain slides open with a rustle and the ceremony begins in the darkness of the cinema hall, but also in the dazzling light of the white cube.

[i] Wilkanoc – a portmanteau play on words, combining the author’s nickname “Wilk” (or “Wolf”, from his name Wilczyński) and “noc” (“night”), evocative of “Wielkanoc” (Easter).