No. 35

The Spaces in Between

Karolina Ziębińska-Lewandowska

What do I need photography for? It is an attempt to put order to the chaos around us; an attempt to silence the noise, to introduce harmony, if only for a moment, to search for it through the camera, through the frame, to cut a fragment of harmony out of the world of chaos1.

Teresa Gierzyńska

The time when Teresa Gierzyńska was entering her adult artistic life was a period of a shift in art towards the body, an explosion of conceptual practices. It was also a moment when women, on an unprecedented scale, came to the fore as artists and upset the order in the male-dominated world of contemporary art. Gierzyńska graduated in 1971 and, a few months earlier, Art News published Linda Nochlin’s now canonical text ‘Why There Have Been No Great Women Artists?’. In it, the American art historian analyses not only the reasons for the lack of women’s names in the art canon, but also questions the notion of the genius artist and, more broadly, the system of values defining what is and what is not ‘great art’.

When Gierzyńska, still a student, was working on the shoots that would become part of the series Caresses and About Her, Lucy Lippard organised radical, postminimalist and conceptual, and later feminist exhibitions known as the Number Shows (1969–1974). She presented there the works of such artists as Alice Aycock, Eva Hesse, Valie Export, Louise Bourgeois, Yoko Ono, Alice Adams, with preponderance of video, photography, texts, manifestos and actions. In Warsaw, Paweł Kwiek and Zofia Kulik (with whom Gierzyńska studied at the same time) experimented with performative activities and launched the Studio of Activities, Documentation and Propagation, and in Wrocław Andrzej and Natalia Lachowicz became active — Natalia LL took serial photographs of the love act (Intimate Photography). Meanwhile, since 1970, the Krakow Photographic Society has been organising the record-breaking annual Venus exhibition of female nudes, featuring dozens of photographs verging on kitsch and pornography, 90% by male photographers, selected by men and with prizes for men. They became an impulse for Teresa Gierzyńska to search for her own language to speak about women, their carnality, intimacy, feelings and desire. Having drawn from the very beginning on various disciplines, such as photography, photocopy, drawing, or graphic design, Gierzyńska’s works perfectly fit into that period and the then current of conceptual feminist art. Yet she exhibited and published rarely, and did not try to get closer to the circles of the Remont and Repassage galleries, with whom she had little in common. Neither did she exhibit with the neo-avant-garde members of the Association of Polish Art Photographers (ZPAF) in shows such as The Searching Photographers. The only attempt she made to attract the attention of this milieu was in 1978 when she submitted a photographic collage — a sketch for the series Following Malczewski’s Traces — to the competition of the 1st International Drawing Triennale in Wrocław. This distinct attitude, her own language — oscillating around the dominant aesthetics of the 1970s and 1980s but, nevertheless, different — is paying off today. We are discovering in Teresa Gierzyńska an artist with an exceptionally rich body of work, one that is not easy to categorise and that has been pursued with great consistency. The aim of this text is not to analyse her work in the context of conceptualism or the turn towards the body, but to describe and analyse it from the technical point of view, to examine its sources and reflect on the meaning of the apparent heterogeneity of means.

Diversity of beginnings

Teresa Gierzyńska comes from an artistic family (her grandparents). Her maternal grandmother, Helena Schneider (née Cholewińska), attended Antoni Buszek’s batik studio at the Krakow Workshops and was the first in Poland to use this technique to decorate furniture and other wooden objects2. She died young and Teresa’s grandfather, Roman Schneider, remarried. His second wife was also an artist, Mary Litauer, a student of Tadeusz Pruszkowski. An active painter in the Kolor group, she became involved in the organisation of the artistic life in pre-war Poland and later on in Canada, where the Schneiders had emigrated. Roman Schneider, an architect and interior designer, a graduate of Antoni Kenar’s school and Josef Hoffmann’s Kunstgewerbeschule in Vienna, was Adolf Szyszko-Bohusz’s assistant, worked on the renovation of the Wawel Castle in the 1920s, and was later one of the active members of the Ład cooperative (the author, among other things, of the design for a folding sofa with simple, functional shapes, called the sofa-bed). His sister had a weaving studio in Krościenko, designed kilims and, like Zofia Stryjeńska, combined modernity with folk tradition. So when young Teresa Gierzyńska — growing up in the small town of Rypin, where her father, a lawyer, was sent to work after the war — was constantly drawing and taking photographs, she had the support not only of her mother, who cared about the artistic upbringing of her three daughters, but also of her grandparents, who from Canada, by correspondence, made ‘corrections’ to her sketches. In 1964, Gierzyńska passed her matriculation exams at the age of seventeen and, as she was too young to be admitted to the Academy of Fine Arts, it was decided that she went to Canada for a year, where under the supervision of the Schneiders she was to prepare for her exams to the academy. During the summer she assisted at the Schneider School of Fine Arts in Actinolite (Ontario), which they had founded, and, over the course of the school year, she took evening courses in drawing, made ceramics in her grandfather’s studio and had her first attempts at sculpture. In the autumn of 1965, she enrolled at the Faculty of Sculpture of the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts in the studio of Alfred Jesion, and later Tadeusz Łodziana, both of whom followed the principles of the traditional sculpture in their teaching. She attended Bogusław Szwacz’s drawing studio, and from her second year through the end of her studies she attended the Solids and Planes Studio run by Oskar Hansen, where her grandfather had taught before the war. Here she felt, as she recalls, that she was pursuing a truly creative and opening artistic exploration and that she was working in the spirit of the avant-garde.

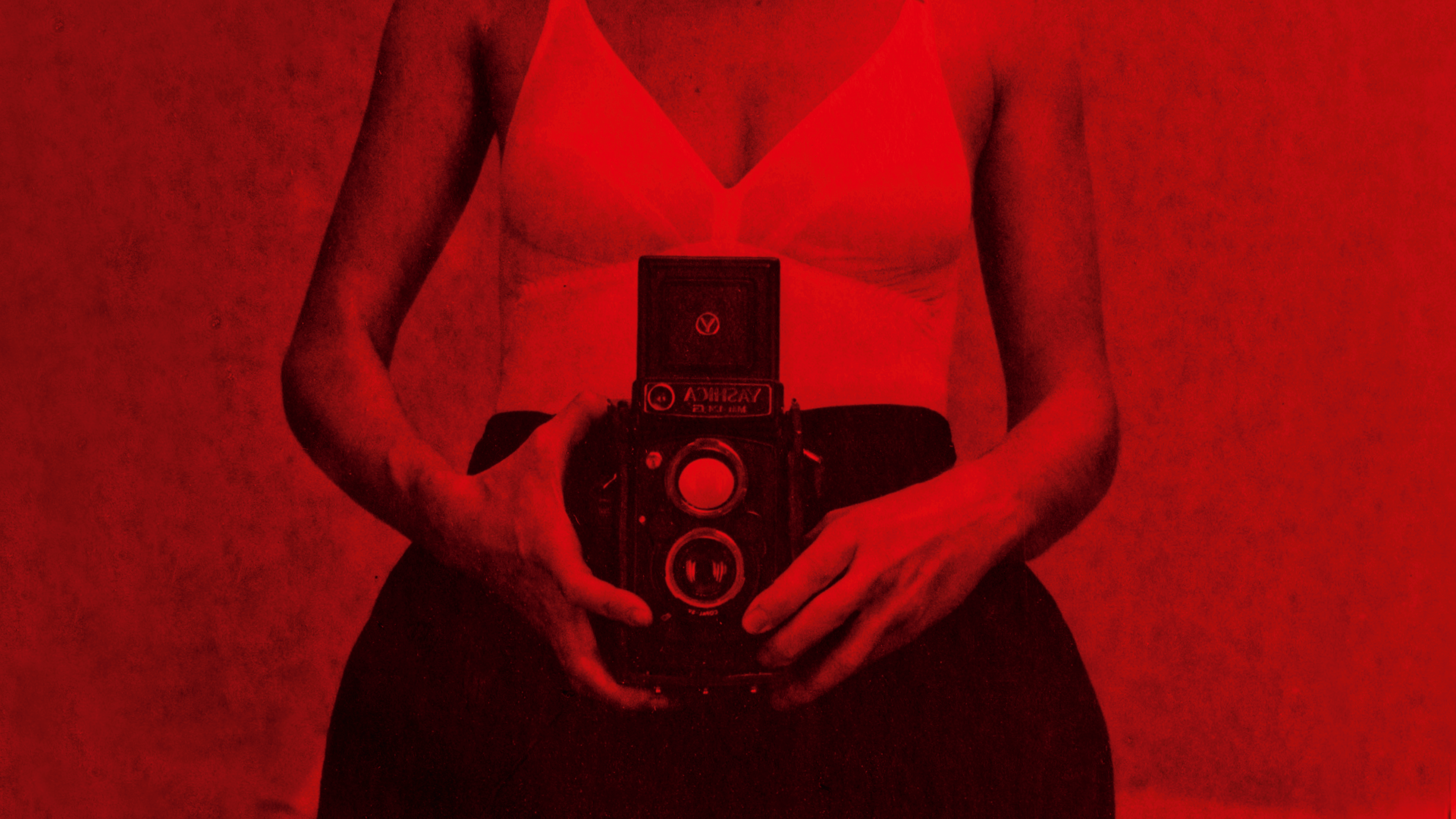

Photography and the solid

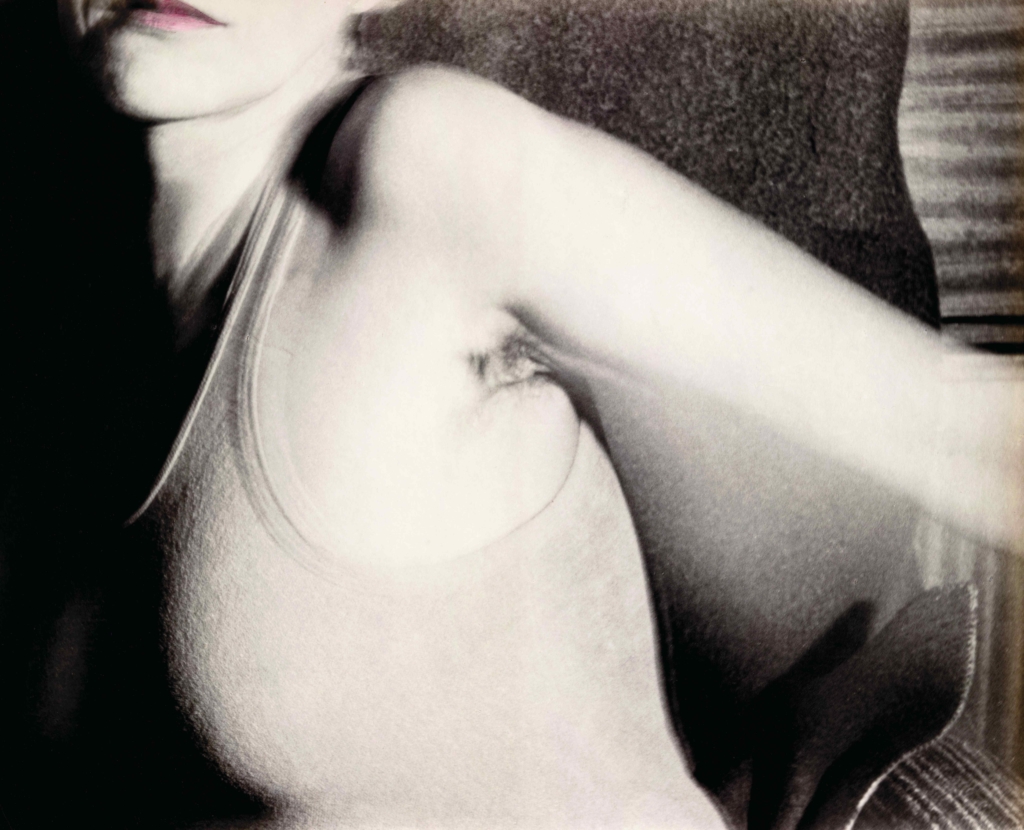

Although photography was not taught in a separate studio at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts, since the 1960s it has been an auxiliary tool in the didactic process at the faculties of sculpture, graphics and design. Gierzyńska was proficient in the use of the camera and darkroom, thanks not only to her family, in which everyone took amateur photographs, but also to the photography classes at the Rypin Culture Centre. Throughout her studies, she took photographs to pass exams both for herself and for her classmates. As part of the work on a sculpture, photographic documentation had to be made at each stage and presented along with the work to be evaluated. In Hansen’s studio, photography was also employed as a tool for practising the interpretation of objects, working with light on a plane, with perspective and scale. After graduating, Gierzyńska made use of the possibilities offered by such a combination only once, in her work The Touch3. It consists of two plaster casts and five black-and-white photographs covered with a thin layer of glaze, making them look like human flesh. The fragments are so tightly framed that they are difficult to recognise. The waist, stomach, back, thighs all take on the qualities of abstraction, or vice versa — after a moment of moving between photographs and sculptures, the abstraction takes on the qualities of a woman’s body. The extent to which this work is a dismemberment of the body into impersonal, unidentifiable lumps is made clear in the working sketch which shows the hand, breast, buttocks, knee, etc. on pedestals, as if in a surrealist drawing. In other sketches, already realistic, we can see a posing model, who is later to be found in black and white photographs. In the next stage, on an enlarger, the frames are narrowed down so as to eliminate points of reference allowing clear identification. The flesh pink of the skin on paper versus the grey of the plaster. The abdomen and hip are cast in a 1 : 1 scale, modelled on votive offerings. The final stage is the title. Each piece has been captioned: Trace, The Daring Place, Form, Cosmos, Line, The Touch. The titles do not serve to specify meaning or guide the viewer — on the contrary, they open up to association. As the artist says, together with the radical frames, ‘they brought me closer to achieving my intended goal: to present transience, anxiety, to suggest what is happening outside the frame — and thus to activate the viewer’s imagination’4. The touch in the title can thus mean the hard-to-name intimacy that exists between the physicality of the body, the softness of the skin, the hardness of the bones and lust, experienced through a tender, delicate touch.

Photography and drawing

The artist’s independence could only be reinforced in Oskar Hansen’s studio, where he would encourage his students to experiment with materials, form, and the frame, instructing them to treat the space of the sheet of paper in a radical manner. As part of one of the tasks in the penultimate year of her studies at the studio, Gierzyńska, who always had her photo materials handy, created a work in which she scratched out an abstract drawing on a several-meter-long piece of unexposed and undeveloped 35 mm film. The drawing made with a jittery, sinusoidal line was created while listening to a rock song I’m a Man by Chicago (1969). The music and the image displayed from the projector were equally important and in harmony during the show in the darkened interior of Hansen’s studio. Gierzyńska then made a series of ten black-and-white prints out of fragments of the film, and coloured them with markers5. The work was close to exercises in abstraction carried out in Szwacz’s studio. Since then, she has regularly used drawing in combination with photography, Xerox prints or reprints.

Photography and print

The lithography studio at the Academy of Fine Arts was a very important place for the artist in developing her own language. In there, some students made lithographic prints of photographic images. Gierzyńska experimented with multiplying motifs, created montages and, while still a student, developed her own method of transferring photos from newspapers and magazines onto paper by means of her own pressing technique. She cut out photographs from West German illustrated magazines, then soaked the lithographic paper in a solvent, laid selected photographs on it and put them under the press. The force of the press caused the photographs to ‘give ink’ to the paper and the result was a kind of a mat pastel print, on which subsequent layers could be printed. The copies were unique, although they made use of mass-produced ready-made images which, as the artist herself wrote, ‘can be interfered with, juxtaposed with others or elevated to the rank of a work of art’6. This is how one of the first series devoted to the images of women came into being, The Essence of Things (1973–1975), composed of 31 panels produced by means of this technique. The images of beautiful, made-up blondes with sensual, but sometimes consciously distorted lips, enhanced with red ink, are faded, seem to disappear, as if they were behind a thin curtain. In the panels Marylin Style or Smile the multiplied faces of the models differ only in shade or intensity of colour. The grid of women’s faces resembles, on the one hand, Andy Warhol’s multiple silkscreen portraits, and on the other, the many feminist conceptual works of the 1970s, which often played with the culturally encoded images of women — the ideal, elegant housewives, tender mothers and beautiful lovers popularised in illustrated magazines. The pastel colours make them seem even more unreal and artificial.

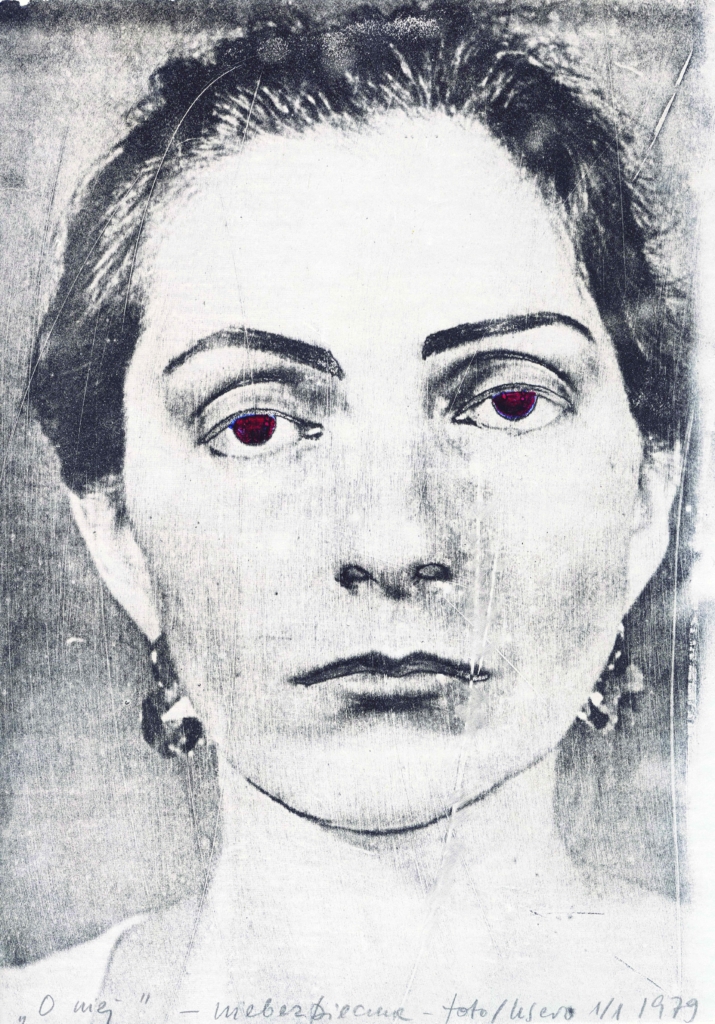

Photography and copy

Fascinated with the imperfect forms of photography, in 1974 Gierzyńska discovered a new technique for creating mechanical montages — with the use of a photo-copying machine. The Pyłorys, a device for making copies of historical documents in the Lenin Museum in Warsaw was made available to the artist thanks to a friend. Sensitive to various reproduction techniques, she used it to produce images of novel quality. The first production phase of works like Memories or Portraits begins with a pen or a pencil. Then a matrix is created. The artist arranges or glues photographs — family, own or found — on a cardboard, together with fragments of magazines, drawings. She also adds captions. Then the whole thing is copied on the said machine capable of producing a maximum A4 format. She will later use them in such cycles as Letters or Love. The effect is more than imperfect, yet the artist titles, dates and signs these copies, combines them into larger planned formats and cycles. It is this imperfection, inaccuracy, reduction of tones that she is after. Most of the series created with this technique deal with memory — be it personal, someone else’s or collective: a group of monuments in the series About a City, a French series devoted to Polish emigrants in Lille made from souvenir photographs of a neighbour from Międzylesie, a series about her own family called Memories. These panels, just like memory and the past, are worn out, faded, composed of fragments that do not always fit together and have distorted proportions. ‘For my memento works I often prefer a print with scratches and dust marking the passage of time, I prefer blurred photographs to those having an unnatural sharpness for the eye in all planes, a technical perfection; I make sure that they do not lose the quality of amateur works.’7

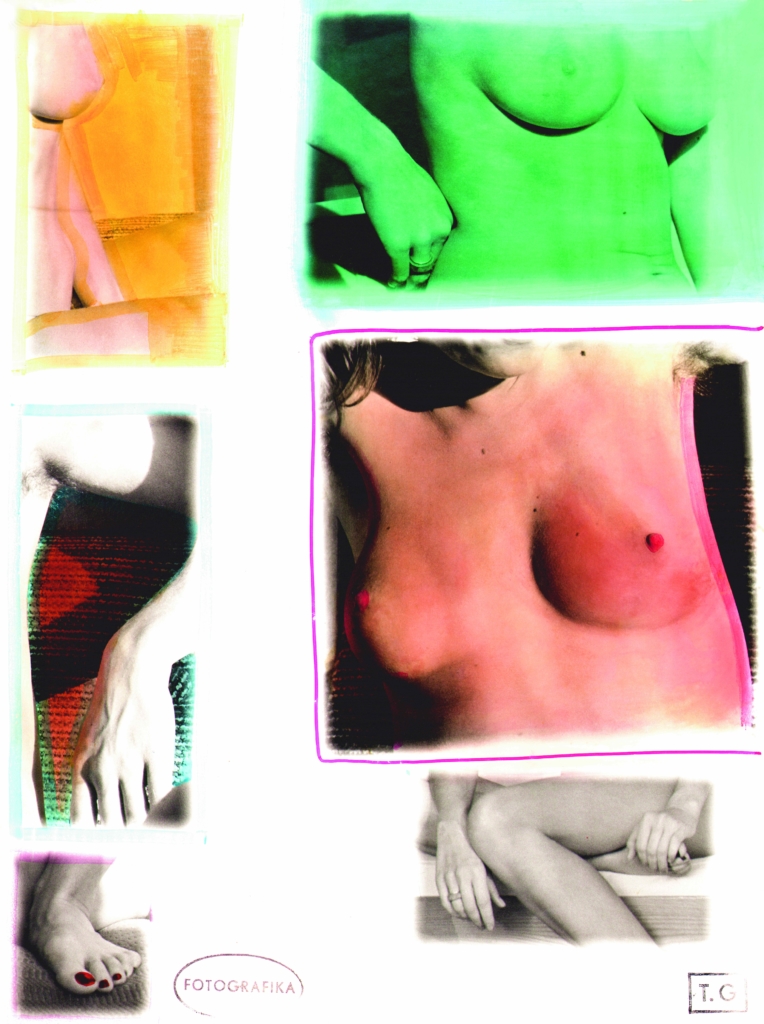

Photography and colour

For Gierzyńska, photography is a material as malleable as a paintbrush or canvas, and at the same time the closest and most accessible one, since she has been employing it since she was fifteen years old. Since her studies at the Academy of Fine Arts, the grey image has been subjected to all kinds of transformations. It may involve multiplication, or perhaps the addition of a layer of colour or stain to bring out certain elements. Sometimes, the paint blankets the entire photograph, acting as a veil or filter separating it from the realism of the shot. The prints made over several days in the darkroom are covered by the artist with aniline, a special glaze used, for instance, by graphic designers — black and white photographs thus acquire yellow, red, green or blue hues. As in the work sent to Wrocław (Following Malczewski’s Traces): fawn-coloured children, fields of ripening crops turn red and yellow under a layer of paint. Thanks to this simple trick, the landscapes become more dramatic. The neutral, often seemingly unsuccessful photographs become expressive images by way of painting, all the more so because one of the most frequently used colours is blood red and pink — the bodies superimposed on the fragments of photographs evoke thoughts of pain, emotions and, above all, they introduce sensuality. The series Caresses, created in 1967–1969, at the beginning of the artist’s stormy relationship with Edward Dwurnik, is the quintessential example of turning photography — a recording tool of scientific precision — into a carrier of emotions and erotic tension.

Photography and text

While experimenting with lithographic presses and magazine prints, Gierzyńska uses fragments of texts and lettering. She expands this theme of her work in such pieces as Anxiety, in which the text reflected from stencilled capital letters covers the entire board. Yet the role of text is important even in short titles. Words bring in a new dimension, expand the boundaries of the works. They are usually not taken literally and do not make use of simple associations. In 1979 Teresa Gierzyńska began the series About Her, an intimate diary of a woman which she has kept to this day. Not a purely autobiographical journal, though often the main character in the photographs is the artist herself. ‘I look at myself and my close surroundings. I talk about intimacy, love, loneliness, femininity, motherhood, growing up, relationships, the complexity of all these things. And in a rather quiet voice, even a whisper.’8 Today this whisper resounds very strongly indeed and moves more than a cry.

The space between

If we try to get a bird’s eye view of Teresa Gierzyńska’s work, it is strikingly nebulous and delicate, thanks to which, paradoxically, it gets to our guts. Undoubtedly, this art touches those spaces that are difficult to analyse intellectually — the sphere of the most deeply hidden emotions, usually covered by a layer of conventionality and disguise. Sadness, loneliness, desire, anger, emotion and that which is difficult to name, because it is in between. One doesn’t wish to or cannot confront it. As is the case with memories and dreams. Again, something intangible that the artist tries to capture in images that have a physical form but do not refer to facts.

To work in these undefined, uncertain, inexplicable areas, Gierzyńska reaches for equally unobvious and undefined tools. She takes photography, which was invented and developed to be a carrier of facts, to convey information about tangible reality as accurately as possible, and creates a tool to communicate something unnamed and invisible.

To show the invisible, to touch the intangible — the reconciliation of these paradoxes and their transgression happens by combining and intertwining means representing different orders. Photography and paint, photography and the word, photography and the solid, photography and print. All these manipulations reduce the realism of the original tool. As the artist herself says, she strives to detach the image from the realism of the photographed world. To record the states of longing and anxiety by modest means. ‘It would be best if there was just emptiness in the photograph, nothing happening, just atmosphere . . .’9

1 Teresa Gierzyńska, Kilka słów na temat pracy [A few words about the work], typescript, artist’s archive, n.pag.

2 Anna Kostrzyńska-Miłosz, Polskie meble 1918–1939: Forma, funkcja, technika, Warsaw: Instytut Sztuki PAN, 2005, p.190; Maria Wrońska-Friend , Sztuka woskiem pisana: Batik w Indonezji i w Polsce, Warsaw: Gondwana, 2008, p. 179.

3 The beginnings of asthma and constant bronchitis prevented the artist from continuing her sculptural activities.

4 Gierzyńska, Kilka słów na temat pracy, n.pag.

5 Teresa Gierzyńska recalls that after the show Oskar Hansen put her in touch with the Experimental Studio of the Polish Radio. However, nothing came out of this cooperation.

6 Eadem, The Essence of Things, typescript, artist’s archive, n.pag.p

7 Eadem, text for SBWA touring exhibition, Photograms, 1981–1982, typescript, artist’s archive, n.pag.

8 Teresa Gierzyńska in conversation with Małgorzata Czyńska, unpublished interview for Wysokie Obcasy (Gazeta Wyborcza supplement), 2017, typescript, artist’s archive, n.pag.

9 Eadem, Podróż [The journey], 2018, typescript, artist’s archive, n.pag.