No. 24

“Lego. Concentration camp” and the problems of sculpture in Poland

Zbigniew Libera

The latest issue of the magazine opens with a text by Zbigniew Libera from the book accompanying the exhibition Sculpture in Search of a Place.

Exerpt from the book accompanying the exhibition Sculpture in Search of a Place. Edited by Anna Maria Leśniewska, Warsaw 2021.

Although I have never considered myself as a sculptor or my work as sculptural, I am no stranger to topics related to sculpture. After all, probably all artists who professionally deal with various forms of visual art know something about it. By that I mean, in short, a better or worse understanding of the third dimension or the sense of space. As for myself, back in the 1980s, I spent a couple of years taking a sculpture course under the supervision of Zofia Kulik and Przemyslaw Kwiek at their base (Workshop of Activity, Documentation and Dissemination, PDDiU) in Dabrowa Leśna. Initially, I put together spatial forms out of loose elements made of various materials, and later I also welded machine fragments found at a scrapyard, to finally construct three-dimensional forms out of sheet metal or metal pipes. My goal was not to make a big thing out of creating art in the form of sculpture. I just wanted to get a practical grip on the problems of constructing three-dimensional objects. Just for the sake of my own experience.

On the other hand, I had long been interested in the history of art, and especially the history of art in Poland. Let me remind you that a few years ago, together with Aleksandra Panisko, I produced over 50 episodes of an educational TV series Libera – Art Guide for the TVP Kultura channel in cooperation with the Art Museum in Łódź, as well as an exhibition at the Królikarnia gallery in Warsaw titled It’s not my fault this sculpture brushed against me to celebrate a jubilee of the sculpture collection of the National Museum in Warsaw. All those experiences as well as my earlier and later studies in the field have brought me to the conclusion that sculpture, unfortunately, has not had luck in Poland. It is difficult to offer an unequivocal explanation here, but generally one needs to note the poor knowledge of the Poles in this matter (the average citizen cannot tell glass from plexiglass, plaster from marble, etc.), poor technical accoutrements, but, above all, the negative disposition of the authorities in all previous eras. There are few European countries with so few sculptures standing in the public space for their own sake, rather than merely to commemorate some government’s favourite. This opinion cannot be changed even by the unique city of Elbląg, which, incidentally, owes its sculptures to the determination of one person – Gerard Blum-Kwiatkowski, who once insisted on organizing the Biennial of Spatial Forms there.

Everything indicates that Xawery Dunikowski was the first artist to make art out of sculpture in Poland. Before him, in his own words, “it looks as if nothing had happened”. Objectively speaking, there were only monuments. Monuments or statues in honour of. Dunikowski showed that sculpture could be an independent artistic expression. What I primarily mean here is the Young Poland period of his art. Despite initial resistance, however, he managed to convince the “traditional Sarmatian heads” that sculpture is art, not just public vainglory. Nevertheless, later, both before and after WWII, commissioned by the authorities, he made many monuments in honour of. Examples include the statue of Józef Dietl in Cracow, unveiled in 1938, and the St. Anne Mountain Uprising Monument, unveiled in 1955.

Even though he did not make any significant artistic breakthrough, Henryk Kuna created sculptures of exceptional beauty in the spirit of the so-called new classicism. Two of them can still be seen in Warsaw parks today. I am speaking about Rhythm (1931) in the Skaryszewski park in the Praga district and Alina with the jug (1936) in the Żeromski Park in Żoliborz.

Katarzyna Kobro found it much more difficult to convince the Poles that sculpture deals with nothing else but spatial relations. It happened as if perforce, probably spurred by the growing popularity of the Athens Charter, the principles of which affected the decision to build modern housing estates built all over Europe after WWII. Unfortunately, Kobro’s own art did not find followers of her calibre and she was pushed into a gap between the painter Władysław Strzemiński and the architect Oskar Hansen, who designed several modernist housing estates, much to the misfortune of those who lived there.

But Hansen, eventually played a more fortunate role in the history of Polish sculpture, as helped by Jerzy Jarnuszkiewicz, his colleague at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts, he trained several young sculptors who applied his theory of Open Form and transformed its architectural concepts into neo-avant-garde art theory. Most notably, these were Zofia Kulik and Przemysław Kwiek, who decided that sculpture is actually a process taking place in time and space, rather than a finished, more or less perfect form. The KwieKulik duo showed that traditional sculptural forms are not autonomous, but they are contained in a series of many complex relationships of the contemporary world. In fact, it was all about realizing the many ways out of seemingly already defined formal situations. Examples of KwieKulik works from the 1970s include activities on the statue of Moses, Man-Prick, Variants of Red/The Path of Edward Gierek or Activities with Dobromierz. Those who created in a similar vein included Paweł Freisler, a promising artist who quickly disappeared from the Polish artistic scene, as well as Marek Konieczny and others, whose names I will not mention here. The reason why I do not mention these names is that I am writing only on my own behalf, as an art lover, and I do not feel obliged to follow the principles of academic art history. I only mention things that touched me personally and, which is probably not without significance, influenced me as an active artist. Who knows, maybe my subjective perspective will tell you more about the history of sculpture in Poland and its possible future than a reliable scholarly account?

Coming back to the topic, I would like to draw attention to the artistic endeavours of Jerzy Jarnuszkiewicz, mentioned earlier in the context of academic teaching. A figure of two, if not many faces, he was, on the one hand, the author of impressive geometric, highly rhythmic sculptures in the post-constructivist spirit, and on the other, the creator of patriotic statues in honour of whose value lies only in national sentimentality. Last but not least, a medallist, and as mentioned before, a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, he was apparently very supportive of free development of students.

Earlier, in the 1930s, we saw the failure of a very promising project, initiated by Dunikowski, then professor of the Cracow Academy of Fine Arts – work by Henryk Wiciński, whom the master himself designated at that time as “a man of our times”, and by his partner Maria Jarema. Wiciński died in the hospital of St. Lazarus as a homeless person in 1943, while Jarema abandoned sculpture for painting in the post–war period. Had they continued with their work, it would have probably developed into the type of sculpture associated with Henry Moore which, as is well-known, we could not appreciate in Poland for various, primarily political reasons.

It is impossible not to mention the phenomenon occurring at the turn of the 1950s, when sculpture in Poland was dominated by women. It was related to the “two Alinas”, as the newspaper headlines of the time would proclaim. One was Alina Ślesińska, the other – Alina Szapocznikow. The former began her staggering international career already after her first individual exhibition in 1957 and at the beginning of the 1960s developed an original concept of sculpture – “propositions for architecture”. However, her promising work was abruptly interrupted at the end of that decade, when she returned to Poland from London, where she had previously intended to stay permanently (she even gave up her Polish passport). As an act of revenge, she was never allowed to pursue sculpture again.

Alina Szapocznikow, a former prisoner of the Terezín concentration camp, after its liberation studied at the Prague University of Arts and Industry (UMPRUM) and later stayed in Paris before returning to Poland in 1951, responding to the appeal of the then Minister of Culture. Initially, she made Socialist Realist sculptures with great success, only to move to Paris finally, in the early 1960s, where she began to work in the spirit of the New Realism that was just developing in France. From the mid-1960s, she began to make body casts, mainly of her own body, using a new material – polyester which was not available to artists from behind the Iron Curtain at that time. She died prematurely in the early 1970s, but her work enjoyed its little renaissance a few years ago. Another important figure in this part of the text is Magdalena Więcek, whose abstract metal sculptures from the turn of the 1960s could, in my opinion, stand in one line with the world’s best artworks of the time.

In the early 1960’s, yet another student of Dunikowski’s, Jerzy Bereś, began to see sculpture as something that returns to its original source, inspired by the hippie ideology of the period, and developed it into a series of performances featuring his own naked body. The object itself emerged, as it were, from his body and accompanied him as a kind of extension, just as tool is an extension of the hand. In the early sixties, he embarked on an unforgettable trek from Krakow to a nearby village, covering about

10 km stark naked. And yet he managed to get there and back to the city without serious injury.

Roughly at the same time, we also witnessed the appearance of the brilliant Władysław Hasior. A graduate of Antoni Kenar Secondary Art School and a student of Marian Wnuk at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts, he began to construct his sculptures using everyday objects, instead of chipping stone or wood or moulding clay or plaster. He even used fire as a material for his sculptures. And when he really wanted to form something, he would dig a mould in the ground, reinforce it with iron, and pour in concrete.

In turn, Edward Krasiński, derived his sculptural objects directly from drawing, or rather from the line that constitutes the basis of drawing. The line that is like a spear cutting through the air, the line that connects things, the broken line, a disorderly cluster of lines or lines wound around something. And finally, the blue line, wherever you look, at the height of 130 cm. Explaining the choice of this particular height, the author said anecdotally that he was inspired by the white stripes on police squad cars. I think there is more to it than merely an offhand joke. These stripes designate a territory and, at the same time, its closure, the boundary of certain space. Still, Krasiński’s blue stripe is a non-sculpture that appropriates space, everything on which the gaze of a single subject can fall.

In more recent times, Krzysztof M. Bednarski, who is only several years my senior, has become known as an interesting sculptor. In his “post-modern” way, he uses familiar shapes to create sculptures and draws on contemporary myths. For example, when he duplicates Karl Marx’s head in a variety of ways and in various materials, or when he builds a figure of the Sphinx from matchboxes, or Three graces from drawing practice mannequins. Sometimes he also uses literary references, for example when he calls an overturned boat Moby Dick or creates a series of spatial objects, recreating the hourglass and diamond patterns from a poem by Dylan Thomas. Bednarski is also the creator of remarkably successful monuments, made in the spirit of modernity, such as the one commemorated to Federico Fellini in Rimini, in which the director’s profile reveals itself in the town square only in the evening, after the lights are turned on – just like in a cinema. Another example is Krzysztof Kieślowski’s tombstone at the Powązki cemetery in Warsaw.

One cannot help but mention here the sculptor who, in the opinion of the general public, enjoys the greatest success among all contemporary Polish artists. This is naturally Mirosław Bałka. Already when he was studying at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, he had a reputation of being exceptionally talented. Initially, he worked together with Mirosław Filonik and Marek Kijewski under the aegis of the Neue Bieriemiennost group, creating sculptures that usually belong to the wave of European neo-expressionism of the 1980s, such as Remembrance of the First Holy Communion or When You Wet the Bed. Later, he managed to jump the last bandwagon with minimalist art heading for the past. One must admit, though, that he did it in his own unconventional, quite elegant way. Many titles of his works could be listed here, but I will only mention the unforgettable How It Is in the Turbine Hall at Tate Modern in London (2009). Bałka is also the author of the Memorial to the Victims of the Estonia Ferry Disaster in Stockholm.

At the end of this hasty sketch about the history of Polish sculpture, we should also mention Paweł Althamer. Educated at Grzegorz Kowalski’s studio at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, and therefore familiar with a kind of afterimage of Hansen’s Open Form, he pursues his activity in a two-pronged manner. On the one hand, with almost a juggler’s dexterity, he is able to make sculptures out of any material and in any style, like in Standing Figure from 1991 made of grass, straw, hides and animal intestines, or Wars and Sawa made in concrete in 2020. On the other hand, following into Joseph Beuys’s footsteps, he practices a kind of social sculpture, animating the activity of various groups of people with whom he collaborates. Let us mention Bródno 2000, when he persuaded the residents of a block of flats in a Warsaw housing estate to create the inscription “2000” by turning off or on the lights in their flats. Sometimes he also manages to persuade other people to act on his behalf, as when he got prisoners to wear a path during the Skulptur Projekte in Münster in 2007. This type of action has even been given its own name: “delegated performance”.

Although it is a three-dimensional object, my artwork Lego. Concentration camp (1996) does not fit in, or, alternatively, goes far beyond the area of sculpture. Contrary to most avant-garde and neo-avant-garde artists, I am not dogmatic, so I leave the decision for the viewer/recipient to decide. After all, this project is not about belonging to any special category. Working on it, I did not think about expanding the field of sculpture or any other artistic discipline. Like other pieces from the Corrective devices series, Lego. Concentration camp was planned, broadly speaking, as a critique of the capitalist system. In the 1990s, capitalism was just coming to Poland and one could observe its modus operandi in all its vividness – something that seems impossible today, because having been completely absorbed into it, we have lost the necessary distance. Now, it seems that our civilization has been striving to reach this state from the beginning and has reached it for good, as once stipulated by Francis Fukuyama in his famous book. And yet, in light of the climate crisis caused by unbridled capitalist greed, the masses of citizens may soon be deeply disappointed.

Capitalism presents itself primarily as a commodity, and back then, in the 1990s, I saw it fit to use that language. The language that is understood and approved by the overwhelming majority of my fellow countrymen. After all, temples larger than churches have been erected, temples for the worship of goods. A good citizen is one who consumes a lot. But goods are only seemingly something utilitarian, they are an idea designated by a three-dimensional object that can be purchased. And when we think we own something, the thing owns us, because, putting it bluntly, it teaches us with itself, it makes us adapted to itself. Doing the Corrective Devices series, I did not intend to create something aesthetic, something just to look at, but I wanted to make things that can be used.

The sense of the entire series lies in their function, which educates the users, in this particular case the viewers of art exhibitions, just as everyday objects change and shape their users. The aesthetics applied here is merely a quote from relevant topicality to make the viewers feel at home, so that they do not get scared by some perhaps overly sophisticated style of the so-called high art. One can say that we are dealing here with Duchamp’s ready-made concept in reverse. While Duchamp was more concerned, in short, with pulling the plane of art composition over ordinary everyday life, my objects were to infect it with a virus revealing its other face. If one were to seek an analogy, it might be more appropriate to refer to the technique of détournement first used in the 1950s by artists from the Letrist movement, and later used widely by the Situationists. However, I would like to point out that when I was working on Lego. Concentration Camp I knew nothing about détournement. The first Polish edition of Guy Debord’s book Society of the Spectacle was published only two years later.

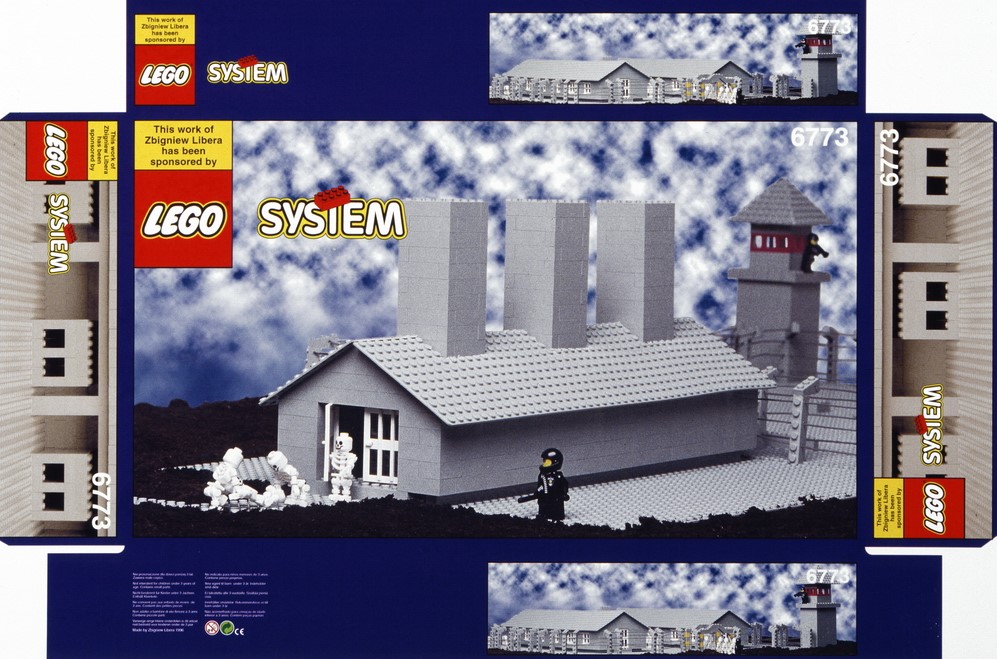

So a commodity itself is not merely a more or less useful three-dimensional object. It also includes a user guide, packaging in the literal sense, the box on which we can see examples of its possible applications, but also in a figurative sense – the general sense of its use. It also involves the entire advertising campaign, big or small, arousing the desire for the object. Finally, it entails the manufacturer’s brand, with its often almost mesmerizing power, comparable only to the power that the Olympic gods. Creating Lego. Concentration Camp I used all of those elements. So here we have grey plastic bricks that the Lego Company custom-made for me; I slightly modified some of them to build a mock-up of a concentration camp with a gate and a double electric fence. We have boxes with bricks inside, with dozens of colourful pictures showing how to use these bricks and figures to play. Actually, it was the packaging that required the most work and contributed to making the piece so powerful. Finally, we also have the brand: the Lego company – although intangible, it also became the material of this work. Each of the seven boxes with appropriate serial numbers has a plate with the following text: “This work of Zbigniew Libera has been sponsored by LEGO”.

Last but not least, the Lego bricks from the Concentration Camp set, just like any other toys and items from the Corrective devices series can and should be used to play. They were designed to be used. However, because we are in the territory of art, so in a gallery, so in a museum, their function remains only potential. Certain rules apply here, such as that one is not allowed to touch the exhibits. Who would allow the possible destruction of a unique and therefore valuable object anyway? This convention was understood perfectly well by the reviewer Dirk Schumer, writing in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, who in March 1997, when the fierce discussion about the future Holocaust monument in Berlin was still continuing, noted that rather than building yet another monument in honour of, the best option would be to introduce the Lego. Concentration Camp set into mass distribution. Monuments, as it is known, facilitate forgetting. Playing with my Lego set could be helpful in the treatment of traumas, both for the victims and the persecutors, as well as their descendants. The notion also highlighted by the philosopher Ernst von Alphen in several of his texts devoted to this and other issues related to my work. Do we not treat traumas clinically by having patients re-enact paratheatrically the various roles that contributed to the traumas? Sometimes there is no other way to express what has been done to us except by re-enacting the trauma in play. Someone may say that the victims and perpetrators of the Holocaust do not need therapy, because most of them have already departed from this world. I can only answer that since the end of World War II until today no single day has passed in the world without a concentration camp operating – at the time when in 1996 I was thinking about Lego. Concentration camp, the latest camps were being built in former Yugoslavia, including concentration camps for children.

Warsaw, July 2020