No. 37

When Nothing Is Happening

18.07.2022

Agata Sikora

They who believe in eternal return, in the same river in which the subsequent generations step, is imprisoned in the kaleidoscope of their own imagination. However complex the images they create, in fact they play with a handful of beads caught in the mirror trap. There is something more delusive than the belief in the uniqueness of one’s own sensibility, feelings, emotions – it is the belief in their universality.

We are entering a minefield here. Because what are emotions in general? Encyclopaedia Britannica defines emotion as ‘a complex experience of consciousness, bodily sensation, and behaviour that reflects the personal significance of a thing, an event, or a state of affairs.’ According to Oxford English Dictionary, it is ‘a strong feeling deriving from one’s circumstances, mood, or relationships with others.’

Both these definitions embed emotions in the individual body, and both inscribe them in a psychological frame. This frame posits that emotional life is governed by the principles of pleasure and bitterness, hormones, chemical reactions. If any story is possible in this regard, it must be personal; if any relations – then preferably family ones. Seen from this perspective, fear, horror, desire, love, regret, distress seem eternal and common for everyone, constantly enacted anew in innumerable tragedies, ecstasies, horrors, ends and beginnings of the world.

Yet, there is another side of this coin: even if certain reactions have a biological underpinning shared by human and non-human animals, the manners of experiencing, understanding and discharging them by people are largely socially shaped. Our feelings are mediated by symbolic imagined visions, negotiated through language, rooted in the contexts of institutions, technologies and social systems. Mourning is experienced differently in a society in which balance can only be regained through bloody revenge, and differently when more than half a year of distress is recognised as an illness medicated with antidepressants. In Western culture, emotional expectations towards women are different from those towards men, different rules of regulating emotions apply to public space and to private space, to work and to leisure time. Different people’s reactions to fear depend not only on the individual level of adrenaline, but also on the cultural patterns of how a given person should react to fear depending on their gender, age, social standing, race, sexual orientation: a soldier ‘should’ do something different with his fear than a young mother, or a black teenager. Moreover, our affective states change with the words we use to describe them – in this case it is not certain that a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.

Therefore, aside from the psychological frame, there is also another way of thinking about emotions, focussed on social contexts. Tellingly, however, the subdisciplines that concentrate on this topic – sociology, history and anthropology of emotions – emerged only in the second half of the 20th century and still retain a limited presence in the collective imagination. Meanwhile, popular psychology promises hope of healing, improving the quality of life, a secular counterpart of redemption and remission of sins. It offers a vision of a privatised world, locked in a family glass ball, in the drama of a personal trauma. This generates the illusion of a limited yet individual control… and a sense of guilt if control cannot be effectively exercised.

In turn, sociology, history and anthropology offer theoretical considerations, academic descriptions and, in the best-case scenario, a meta-critique of the system. If they suggest any solutions at all, these apply to the field of social change. And this sphere – unlike the search for your inner child or breathing exercises – appears as abstract and detached from everyday life.

Is this not puzzling given the dramatic social changes that have occurred before our eyes during the last several decades? Can we imagine a greater span of the arch of the imagination than the one between my generation born under martial law and the young people who came to this world around the turn of the century? Proudly experiencing not our own

veteran memories of empty shelves in shops, we got second-hand polyamide clothes from the West, fake Barbie dolls, the NATO shield, Erasmus scholarships, cheap flights and the mythology of individualism. We were not supposed to engage politically in anything, but just live a longer, happier and successful private life. In turn, growing up with access to the global network, they reached adulthood in a world of junk job contracts, rampant populism, the pandemic, war, and above all the intensifying climate disaster. History, which was supposed to come to an end, returned with an apocalyptic force.

***

Yet, this sense of absolute uniqueness is an illusion. Even if the scale of the threat posed by the climate disaster is objectively unprecedented, does the spectre of a global nuclear war entail any less of total annihilation from the point of view of human sensibility? The 20th century alone saw dozens of smaller and greater collapses of empires, new orders, inventions that revolutionised the lives of billions of people on the planet (such as synthetic fertilisers, vaccinations, contraceptive pill, automatic washing machine). As for the curability of diseases, access to food and life expectancy (also in developing countries), we live in a reality that until the 18th century was a utopian fantasy. It would therefore seem that before the climate disaster gained presence in the collective awareness, we should have experienced satisfaction, a sense of triumph, contentment.

And yet, we did not dance out of joy on the streets or sing the praises of three meals a day and antibiotics. In the same way, we do not react adequately today to the climate crisis we have induced. The part of our sensibility that results from what appears on an everyday basis as the neutral backdrop of reality (and only sometimes is called ‘the spirit of the times’) escapes description using behavioural slogans based on alliteration: fight, flight or freeze. To capture its dynamics, to notice it at all, we need to bid farewell to the illusions of objectivity – come to terms with the fact that our sensibility and cognitive apparatus are also products of a specific time, place, gender, social class.

Therefore, understanding feelings from a social perspective does not promise redemption from the present, let alone guarantee a bright future. However, it cures us of the illusions of determinism. If the biological basis of emotions is treated as given laws of physics, then their social shaping would be analogous to architecture. Paradoxically, a historical perspective opens us up to the future – it makes us realise that similarities are not identities, regularities are not laws, and the world of human meanings is constantly coming into being in the collective dynamics. The fact that you and I cannot influence it with a single action, word, gesture does not mean that it is governed by non-human fate or blind mechanics.

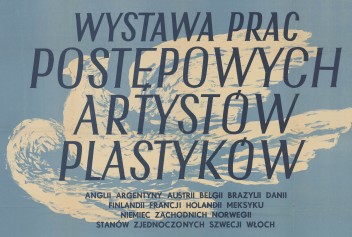

Activating such a perspective does not immediately require delving into scholarly metalanguages: discourse analysis, academic policies of emotions. One of the most fascinating and, at the same time, accessible histories of post-war sensibility is Annie Ernaux’s book The Years (Seven Stories Press, translated by Alison L. Strayer). Juxtaposing her own memories and photographs with advertisements, songs, scandals, political developments, jokes from the era, the French writer born in 1940 seeks to reconstruct what hides underneath dates in school textbooks, transformations of styles, filters of nostalgia. Instead of introspection and expression of the ‘self’, she chooses to look from outside, setting herself-from-the-past in the historically shaped network of everyday pressures. Instead of abstract nouns originating from social sciences, such as ‘welfare state’, ‘depoliticisation’, ‘consumerism’, ‘revolution of mores’, she creates a collage of visual, audial, sensual contexts that shape the emotional life of her generation. Ernaux writes about the most intimate feelings – those relates to desire, sexual shame, maternity – showing that they are not individual. She

uses first person plural, and not singular forms. And if she chooses to evoke her own individual life story, she does so in the third person.

This method obviously has its limitations. Indeed, anathematised by psychotherapists, the pronoun ‘we’ is conducive to projection, allowing for legitimising one’s feelings with a collective consensus, an imagined community… It often serves unfair play, may become a tool of oppression, it is easily seductive. However, the advocates of ‘I’ like to forget that their profound inner lives detached from social contexts are as authentic as an actor in the studio set against a green screen, which someone will one day turn into a city of the future, the cosmic space or a jungle populated by talking animals.

The perspective of history, anthropology and sociology of emotions therefore escapes reduction to tracing the cultural transformations of the expression of artefacts, such as ‘wrath in the Middle Ages’ or ‘romantic love in Papua New Guinea’. It compels reflection on the very frames in which we place what we call ‘emotional life’. Where do we situate emotions? How do we understand subjectivity? Do we believe in the oneness of the objective world or millions of individually experienced worlds? And what infrastructure – discursive, scholarly, material, moral, aesthetic – supports such imagined visions, and not others?

***

Ernaux describes growing up during the reconstruction, in the shadow of an unknown war, in poverty, in the provinces, in a girl’s body trained for shame, passivity and maternity. Having docilely entered the treadmill of the household, work and parenthood, the young mother and teacher identifies with the students’ rebellion. The interpersonal reality is on the point of being created anew in every book, song, gesture. However, the political revolt that was supposed to happen in a month or two, or in a year at the latest, never materialised, and the horizon of utopia was growing ever more blurred. One decade and a half was enough for a permanent economic crisis to become the only ‘reality’; a crisis to which the only response was entrepreneurship, technocracy and correct materialism.

With hindsight, we can wonder whether the radical naturalisation of mass consumption and depoliticisation of language have not led to greater consequences for us and our planet than World War II. And yet, the 1970s and 1980s are commonly seen in history as a period when ‘nothing was happening’ – as if passivity was not as fertile in consequences as action.

This is yet another trap in which our language, perception and imagination get caught: the fireworks of dramatic developments explode in the sky, leaving in the darkness the earthbound realm of our fears, little joys, terror grown commonplace. It is easier to imagine the mythical, mediated wartime than to notice, verbalise and understand the logic of social training we undergo. It is easier to describe strikes, the collapse of the hierarchy of gestures and the ecstatic May certainty that everything will change than the stupefying process of disenchantment – there you are, smoothly riding a bus on asphalt that replaced too subversive cobblestones; there you are, assigning an essay to your students about why material belongings fail to bring happiness, but buying the latest hi-fi yourself.

This is why the cultural theorist Lauren Berlant proposed in her book Cruel Optimism to avoid traumatic narratives in attempts to capture the history of emotions: ‘My claim is that most such happenings that force people to adapt to an unfolding change are better described by a notion of systemic crisis or “crisis ordinariness” and followed out with an eye to seeing how the affective impact takes form, becomes mediated.’

The second decade of the 21st century – half a century after May, which was supposed to mark the beginning of a new world – saw a revival of hopes for the political agency of the young, especially girls, who would also profit from this occasion to smash patriarchy. The Swedish teenager Greta Thunberg inspired the global climate strike Fridays for Future, Malala

Yousafzai from Pakistan became the youngest person ever awarded Nobel Prize, the survivors of the shooting in Parkland, Florida, organised mass protests for the sake of restricting access to firearms in the United States. I myself, who belong, like Ernaux, to a generation that tamely surrendered to the mythology of the fathers, born and raised during the full bloom of apolitical technocratism, was looking with admiration at their social engagement, ability to react to discrimination, expansion of the field of the political imagination, attempts at collectivism.

We need to remember, however, that similarities are not identities, regularities are not laws, and the world of human meanings is constantly coming into being in the collective dynamics. Whereas the revolt of 1968 unfolded under the banner of releasing libidinal energy and was meant to destroy the old order, today it is the young who stepped in the shoes of the reasonable ones while the older generation eagerly resigned from agency, feeding on fantasies about youth that would save the world. ‘I’m most frustrated by how romanticised our generation gets’ – states the school-leaver Martyna, a former climate movement activist, in a conversation with Krzysztof Katkowski. Romanticisation is the most diplomatic form of patronisation, but such superficial politeness does not turn an object into a subject.

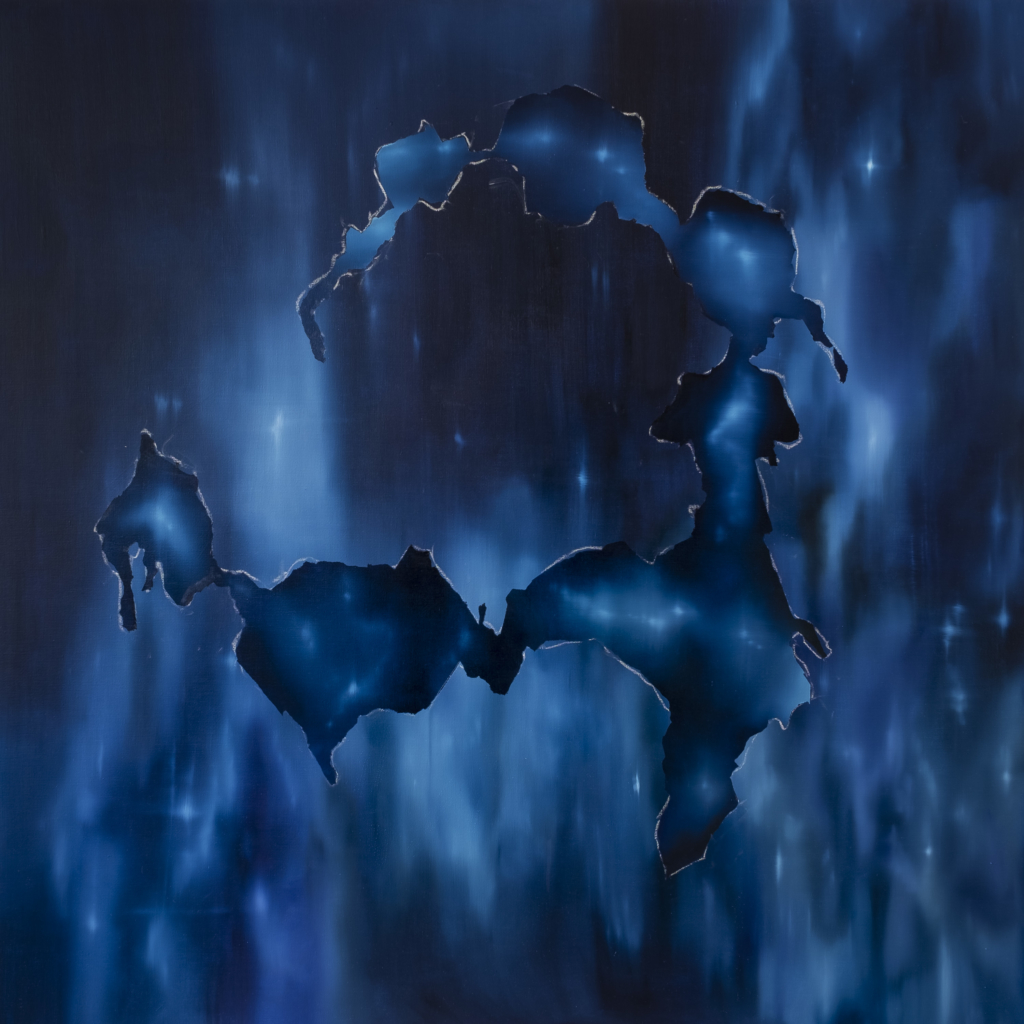

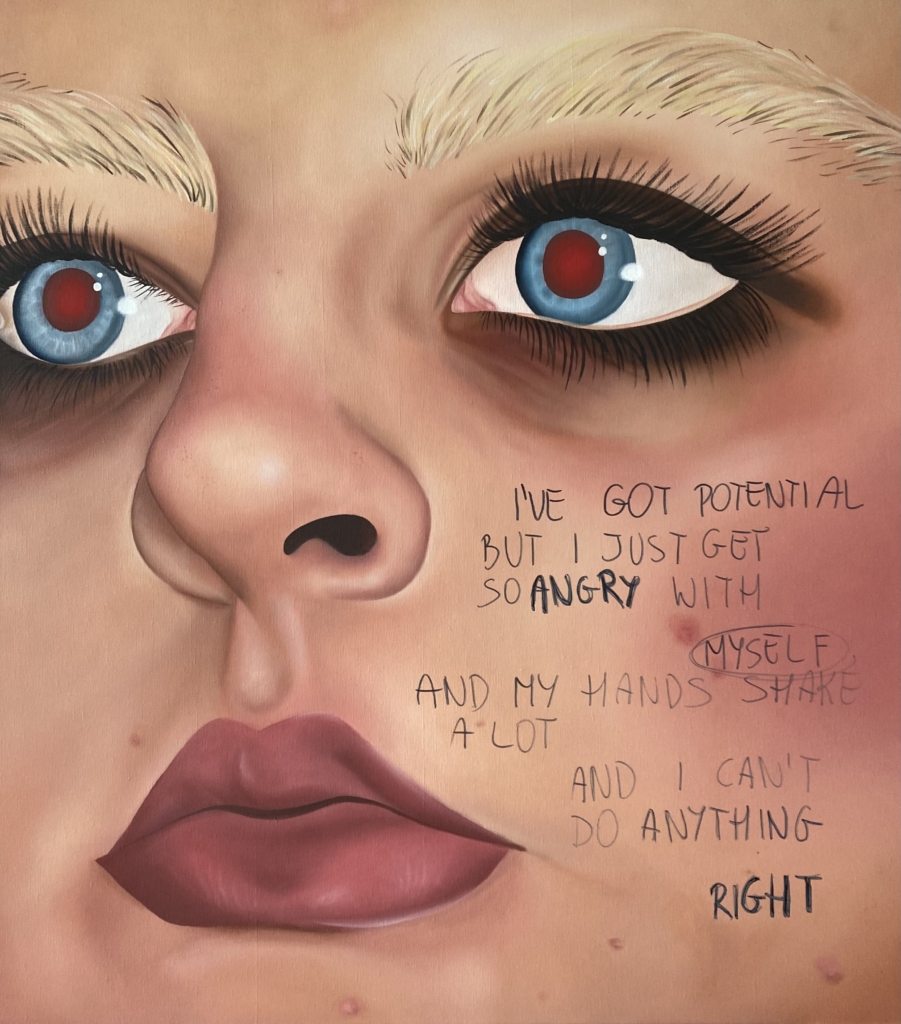

Therefore, if we are to treat so-called young art seriously, let not youngness become a key to it – this handy catch-all, seemingly ‘universal’ trope, in which we can inscribe our own generational fantasies and mythologies. It is better to perceive it as a space of reactions to these constant tensions, ruptures, changes that seek to imitate the lack of events, the existing world, neutral reality. What Berlant called ‘crisis ordinariness’ is possible to grasp and describe when what is internalised in the process of socialisation at a specific historic moment stops appearing as pre-eternal and given.

What affects therefore emerge from the clash between individual sensibility and the architecture of social pressures? What interpretative nets are they caught in; on what frames of meanings are they stretched out? What techniques are used to tame, suppress, affirm, reshape, destroy them? What delineates the underground currents here, and what appears as cold and motionless water depths?

Agata Sikora (1983), doctor of cultural studies. Author of the books Wolność, równość, przemoc. Czego nie chcemy sobie powiedzieć [Liberty, Equality, Violence. What We Refuse to Tell Each Other] (2019) and Szczerość. O wyłanianiu się nowoczesnego porządku komunikacyjnego [Honesty. On the Emergence of the Modern Communication Order]. Permanent collaborator of Dwutygodnik.