No. 34

What did a director of a cultural institution have to face during the time of the Polish People’s Republic?

The case of Gizela Szancerowa

Karolina Zychowicz

Gizela Szancerowa was the director of Zachęta from 1954 to 1969.1 During the period of People’s Republic of Poland , this position was substantially different than today. It primarily consisted of the work of an official implementing the guidelines of national cultural policy (often imposed by the USSR). After 1989, directors of institutions showing contemporary art were given the opportunity to pursue their own original concepts. Although granted much more freedom than their predecessors within the communist system, they were still constrained by political guidelines and subject to pressures from the ministry or local authorities.

Szancerowa took over as director of Zachęta on 1 April 1954: she was 46 years old. De-Stalinization was imminent, so the changing political atmosphere enabled her to show art that had been banned in Stalinist times. Szancerowa studied at the Jagiellonian University, where she completed one year of Art History (1928/29), and then three years of Law. According to her statement, financial difficulties interrupted her studies. In Kraków, Szancerowa was also a member of the Communist League of Youth in Poland (1931-1932). Her career flourished after she began working at the Ministry of Culture and Art. From 1 May to 31 December 1949, she worked in the Warsaw office of the Mickiewicz Committee (initially as an inspector, then as acting director). At the apogee of Stalinism in Poland, she became deputy director of the Office of Artistic Festivals on 1 January 1950, and administrative and financial director at the Central Board of Visual Arts Institutions on 1 August 1953.2 Documentary evidence shows that she was a skilful organiser, but her strong professional position could also be related to the high-powered job of her husband Erwin Szancer, who worked in the Military Team of the Planning Commission at the Council of Ministers as director of Department III from 1949 to 1956, and as deputy director of Department I from 1956 to 19633. Bożena Kowalska reports that the previous director of CBWA Zachęta – Armand Vetulani – was dismissed due to his refusal to join the Polish United Workers’ Party (PZPR).4

Although Szancerowa was friends with many artists (especially from the Kraków Group), she cannot be called a curator. This profession in Poland only emerged in the last two decades: currently, the directors of cultural institutions often have extensive curatorial experience. Szancerowa was a PZPR activist, dependent both on the Ministry of Culture and Art (MKiS) and the Union of Polish Artists and Designers (ZPAP), which performed an influential role at the time.5 This is confirmed by the archival materials quoted below.

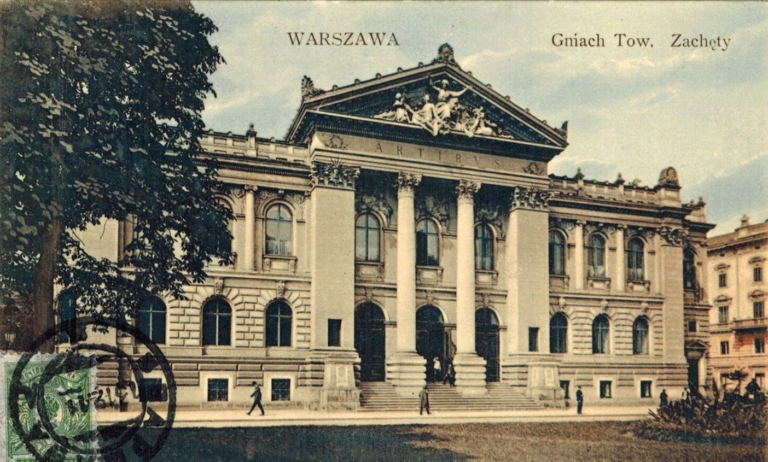

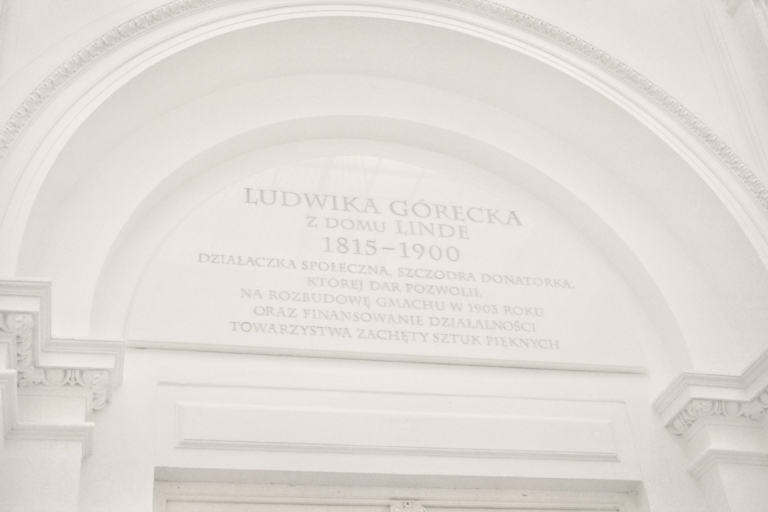

It is sometimes forgotten that Szancerowa was also the director of the entire Central Bureau of Art Exhibitions (CBWA), so she did not only supervise exhibitions at Zachęta. The building of Zachęta – completed in 1900 – belonged before the Second World War to the Society for the Encouragement of Fine Arts (Towarzystwo Zachęty Sztuk Pięknych – TZSP), which had been founded 40 years earlier and attracted artists and lovers of art. Operating under the partitions of Poland, the association aimed at “propagating the fine arts in the country and provide help and encouragement to artists”.6 The exhibitions organised by the Society aroused controversy, as they often featured works of dubious quality, maintained in an academic, often strongly ossified formula. The building, which after the end of the Second World War was the only place in the capital suitable for the presentation of contemporary art, turned out to be most important. The Society for the Encouragement of Fine Arts was not reactivated after the war. In January 1951, the edifice of Zachęta became the seat of CBWA, established in 1949.7

The scope of institution’s tasks can be understood on the basis of the activity plan for 1966. This shows that CBWA’s activity was focused on three areas: firstly, Warsaw; secondly, Poland (the coordination of 15 Bureaus of Art Exhibitions – despite the decentralisation of CBWA in 1962); and, finally, abroad.8 The document reads: “The exhibitions in Zachęta and Kordegarda,9 even if not the key department, are certainly the showpiece of the CBWA. The plan of exhibitions was made in close cooperation with the Visual Arts Committee (at the Ministry of Culture and Art) and the Artistic Commission of the Presidium of the ZPAP Executive Board”.10 The document also contains information on the organisation of paramount all-Poland events, such as the Fine Arts Festival in Sopot, or international ones, such as the International Poster Biennale at Zachęta. Foreign exhibitions “result mostly from international agreements and are financed by the Visual Arts Committee, and occasionally from agreements concluded by the CBWA and then financed from our budget”. A show of paintings from the collection of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam was given as an example of the most recent such exhibition.11 The plan reveals that didactic exhibitions were also an essential part of the CBWA activities.12

Szancerowa was invited to the meeting of the Advisory Commission for Artistic Affairs in the Ministry of Culture and Art.13 The archives of Zacheta contain correspondence between the director of CBWA and Wojciech Wilski, the director of the Visual Arts Committee at the Ministry of Culture and Art. On 13 November 1964, she wrote: “Taking into consideration the proposals submitted to us for the exhibition plan for 1965, the Central Bureau of Art Exhibitions kindly communicates that it will be able to get involved in the events enumerated below […].14 The list includes the São Paulo Biennial, the Paris Youth Biennale, the Guggenheim Award in the USA, and, in Poland, an exhibition of the communist French artist Édouard Pignon as well as a show of Venetian glass. Even in 1965, as in the period of socialist realism, exhibitions from France or Italy were the most gladly hosted because communist parties had a strong position in these Western countries. The document quoted above shows that Szancerowa largely implemented top-down decisions. Sometimes, however, as in the case of the Pablo Picasso exhibitions staged in 1965 and 1968, she directly influenced the programme of the exhibition.15

As already mentioned, not only did Szancerowa have to respect the guidelines of the Ministry of Culture and Art, but also reckon with the authorities of the Association of Polish Artists and Designers (ZPAP). In the discussed period, every self-respecting artist wanted to belong to the ZPAP, because membership meant, above all, material security and the possibility of exhibiting works in official galleries. That is why Zachęta’s archives include numerous applications from members of the Association for the organisation of an individual exhibition. Many requests were met with a refusal from the director for various reasons. Among her letters, several types of replies can be distinguished. Sometimes she responded confirming the receipt of an application and explaining that the exhibition plan “will be considered by the Commission together with the representatives of the ZPAP Executive Board”, and the applicant will immediately be notified of the decision.16 Other documents point to the fact that the exhibition plan of the time was already full. Aleksander Kozyrski received a letter, advising him that “in view of such large events planned in the first quarter of 1967 as the ŁAD Jubilee Exhibition, the Realist Group Exhibition, or the posthumous exhibition of [Sergei] Gerasimov (from the USSR), occupying the whole Zachęta, the Commission could not accept the citizen’s application”.17 Other artists got the same information. Sometimes, as in the case of Adam Gerżabek’s exhibition, Szancerowa suggested: “It would be advisable to organise A. Gerżabek’s works first in Gdańsk or Sopot, and only then in Warsaw”.18 In rare cases, answers to the applications were more personal. The director responded to another request of the above artist for an exhibition as follows: “Despite our best intentions, we see no possibility of organising an exhibition of A. Gerżabek’s works this year. Zachęta, as the central exhibition body in Poland, is overloaded: many artists wait several years for an exhibition, and due to the influx of many exhibitions from abroad, even already scheduled individual exhibitions are often postponed until the following year”.19

I shall present further problems that Szancerowa had to deal with at the time, using two exhibitions as examples: the Second Exhibition of Contemporary Art (1957) and the Exhibition of Contemporary Italian Art (1968).20 The first was organised at the beginning of Szancerowa’s work as director; the second heralded the end of her term of office. Both exhibitions presented the avant-garde: Polish and Italian. It is worth adding here that Iwona Luba describes the then director of Zachęta as “an admirer of the Polish avant-garde and abstract art”.21 Szancerowa’s interest in the avant-garde may have been influenced by her husband, Erwin Szancer, who had studied at the Bauhaus in Dessau during the 1929/30 academic year.

The first of the exhibitions is of extraordinary importance for post-war Polish art, because it represents the apogee of the de-Stalinization of art that had developed after 1955. This event had been heralded by another exhibition from the beginning of the same year, which Luba made a subject of her extensive study. This was a large exhibition of the pre-war avant-garde, victims of Stalinist cultural policy and socialist realism: Katarzyna Kobro and Władysław Strzemiński.22 The exhibition was first shown at the Art Propaganda Centre in Łódź, and then in Warsaw, when the director of CBWA obtained permission to move it to Zachęta.23 Apart from Szancerowa, the avant-garde poet Julian Przyboś – a promoter of Strzemiński’s art – was involved in exhibition’s organisation. The relationships with Przyboś had already deteriorated several months later, on the occasion of the Second Exhibition of Contemporary Art. His unflattering review of that event may have given the authorities an argument to abandon liberalising cultural policy.

The exhibition of contemporary art, undoubtedly the result of pressure from the artistic community of the time, was one of the most significant exhibitions held in Zachęta. It was attended by many artists who were Szancer’s friends: Maria Jaremianka, Tadeusz Kantor, Erna Rosenstein, Henryk Stażewski, Jonasz Stern and Alina Szapocznikow. A sizeable binder of press documentation has survived; therefore, we know that the most important Polish art critics had written about the exhibition.

Ignacy Witz recalled the First Exhibition of Contemporary Art in the following way:

“It was held under the sign of Surrealism, fashionable in Paris at the time. At the present exhibition – apart from [Kazimierz] Mikulski – there is no trace of this direction. Instead, ‘Polish Tashism’ reigns, a reflection of ‘Realité nouvelle’, about which I am not sure if is still fashionable in Paris. My recollections convey the picture of the first exhibition as livelier and more dynamic than the second one. A much less conquering spirit of the new academicism, a kind of wearisome officialism, pervades the current event.”.24

The beginning of Krzysztof Teodor Toeplitz’s article is interesting:

“The Warsaw Society for the Encouragement of Fine Arts was a venerable and conservative association. All rebellions against academicism in art, all innovative impulses were met with stately rebuff by the dignified staff of Zachęta, and violent waves of avant-garde rebelliousness smashed against the bedrock of the classicist edifice in Małachowski Square, never crossing its threshold. […] Thus, the opening of the Second Exhibition of Contemporary Art at Zachęta may seem like a revolution. Or perhaps this contemporary art, until recently practised secretly in painters’ studios and not allowed to be exhibited, has become academic, staid, and harmless in record-breaking time?”25

Jerzy Stajuda explained the significance of this event in a different way:

“There are weak paintings in this exhibition. Very few paintings are perfect. But that is not the point of the exhibition. The point is to show that abstract painting is a universal and profound movement in Poland. That its existence should be taken seriously”.26

The most significant discussion about the event turned out to be Julian Przyboś’s article Sztuka abstrakcyjna. Jak z niej wyjść? [Abstract Art. How to get out of it?].27 It was both the most essential and at the same time the most critical. Przyboś wrote that in front of the entrance to the exhibition there were plaques with the names of members of pre-war avant-garde art groups, as well as works by several of them. “The bulk, most of the works on display depart so far from the style and level of the avant-garde classics that the relationship and covenant are broken. And not as one would expect. This mass of paintings does not defy the classics of new art in a novel, creative way.” He justified his position as follows: “Often it is not the image that is the point, not the visual emotion, but the suggestion of moods that can be evoked by another branch of art, literature or music.”28

From private correspondence between Szancerowa and her friend – the artist Maria Jarema – we learn about the dilemmas faced by the then director of Zachęta. Szancerowa wrote:

“[Julian] Przyboś often comes here and speaks ill of the exhibition; he mentioned to me that he would publish an article in ’Przegląd’ […]. I am worried about the attitude of Przyboś because he evaluates the whole event negatively and voices his views everywhere. It seems to me that his attitude is very dangerous. […] I probably do not have to explain to you what Przyboś’s position means in the present balance of power, and whose ally he is becoming. Naturally, he rushes blindly without realising it. I explained to him my assessment of this attitude and I must admit that it did not go unnoticed. So much gossip about the exhibition – please keep it to yourself.”29

This letter perfectly shows that Szancerowa had constantly to manoeuvre between artistic reasons and ministerial guidelines. She was horrified by the behaviour of Przyboś, who proclaimed on the pages of “Przegląd Kulturalny”:

“The critics from ‘Przegląd Artystyczny’ are doing our Tascists the greatest possible disservice. The former propagators of socialist realism have now thrown themselves with expiatory zeal into writing obscure poetical texts, adorned with metaphors such as: ‘metal constructions welded with fear’.”30

Evoking the recently condemned socialist realism in the context of an exhibition of contemporary art was indeed dangerous, so there were reasons for the director to worry about the programme of her art institution.

Ten years later, however, she was still head of the CBWA. A meeting about exhibitions plans for Zachęta and Kordegarda in 1968 was held on 13 October 1967. This was the consequence of the report that Gizela Szancerowa was ready to perform her function for the next few years. The minutes read: “She informed the participants that discussions about the plan should not be limited only to 1968, but the CBWA activities related to major events for the following years ought to be covered as well.”31 However, 1968 was her last year at Zacheta, and she retired on 28 February 1969. Her husband, who worked as a deputy director of a department in the Planning Commission at the Council of Ministers, lost his job. The Szancers decided to emigrate for several decades until their deaths. This decision had presumably been conditioned by the political situation in Poland.

On 5 June 1967, Israel, expecting an attack, destroyed the ground bases of Egypt and Syria, starting the Six-Day War.32 After two days, the Egyptian army had been defeated, with Israeli soldiers almost reaching Damascus. The media reported unconfirmed information about the cruelty of the Israeli army. The events were compared to Germany’s attack on Poland in 1939, and Israeli commanders to Nazi marshals. The balance of forces between the superpowers was upset, which triggered an inevitable reaction from the communist states: the Polish People’s Republic broke off diplomatic relations with Israel on 12 June 1967. Seven days later, Władysław Gomułka, at the opening of the Trade Union Congress, proclaimed: “We do not want a fifth column in Poland”, giving rise to an anti-Semitic campaign. The Security Service began making a list of Poles of Jewish origin. One of the important reasons for increasing anti-Semitism were factional clashes within the PZPR itself and among the party leaders.

It was under such circumstances that a pivotal exhibition took place in the last year of Szancerowa’s term of office as director. The exhibition Contemporary Italian Art (1968), although it presented artistically excellent works, seems interesting to me for other reasons. It was shown in March 1968 and heralded the end of an era: the exploration of the achievements of the de-Stalinisation. Witnesses report that the event was the result of Szancerowa’s international contacts.33 The halls of Zachęta emptied, and the public were rather interested in what was happening on Polish streets. In January of the same year, Kazimierz Dejmek’s Dziady (a performance of a Romantic play by Adam Mickiewicz) was taken off the stage, which led to the so-called “leaflet war”. On 4 March, Adam Michnik and Henryk Szlajfer were expelled from university at the request of the Minister of Higher Education for informing the French press about the disturbances. The authorities of the University of Warsaw declared the gatherings illegal on 7 March, but students continued to meet the next day. Reportedly, the atmosphere was calm, but when it was decided to end the gathering, several buses marked as “trip” appeared with ZOMO members (ZOMO – Militarized Reverse Units of the Citizens’ Militia) and “workers’ activists” – largely composed of ORMO men (ORMO –Volunteer Reserve of the Citizens’ Militia). Prof. Zygmunt Rybnicki conducted negotiations with a delegation of students, as a result of which, after hearing their demands, the militia left the university. However, they returned after an hour and, together with ORMO members, started to repress not only students but also the academic staff.

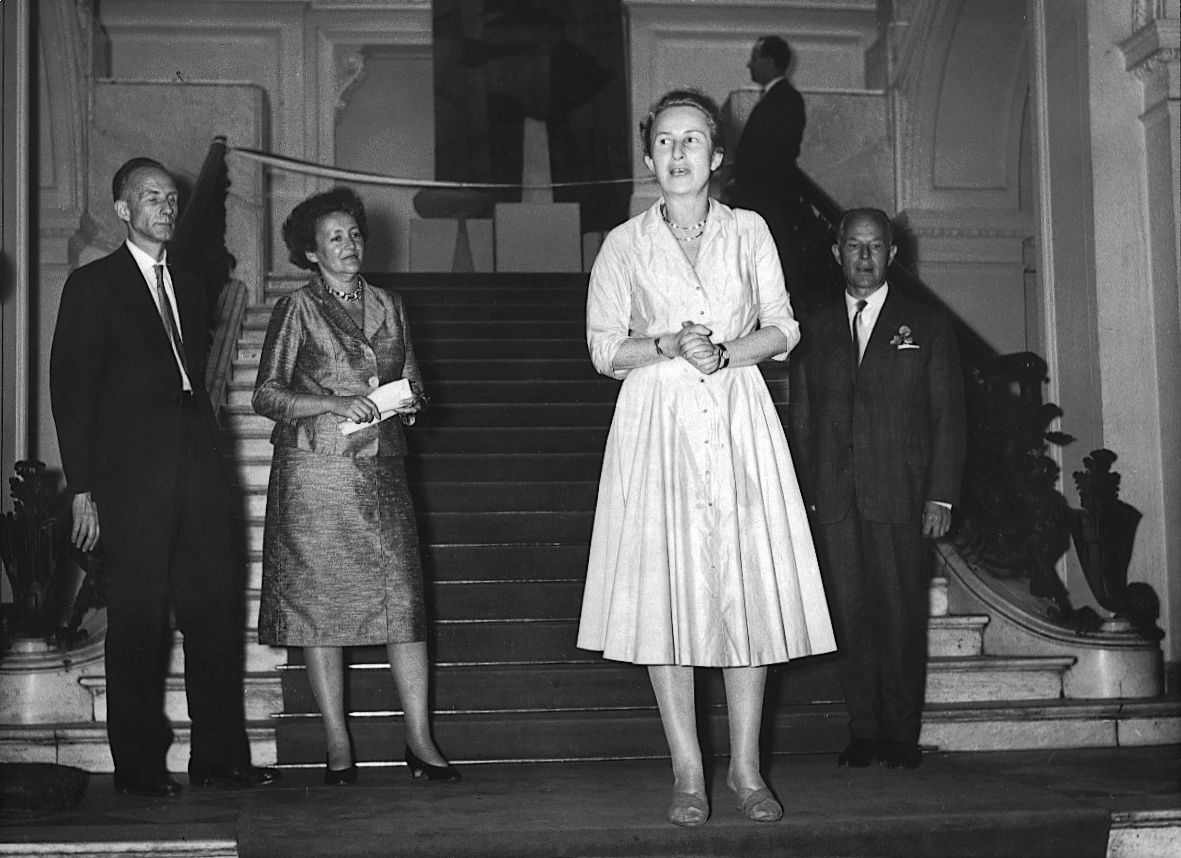

The opening of the exhibition – scheduled for 11 March – took place despite the recent riots. The newspapers of the time report that many important personalities attended the vernissage: Deputy Minister of Culture and Art Zygmunt Garstecki (who opened the exhibition), the Director of the Department for Scientific and Cultural Cooperation with Foreign Countries at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ambassador Henryk Birecki, and the Italian Ambassador to Poland, Enrico Aillaud. Moreover, according to the newspaper “Trybuna Ludu”, “there were also representatives of the Italian art world, including the Director General of ‘Gallerie di Roma II’, prof. Palma Bucarelli”, as well as “numerous representatives of the cultural world of the capital city”34. Everything was as if nothing had happened on the streets of Warsaw. The papers “Ilustrowany Kurier Polski” and “Dziennik Bałtycki” published a photo of the opening of the exhibition.35 It is telling that the presence of the director of CBWA Zachęta – Gizela Szancerowa – was not mentioned, although she can be spotted in one of the photographs. An amused company is occupying the foreground, while an aloof woman is standing in the background. Her face is hidden by one of the men (most probably Zygmunt Garstecki). The vernissage was graced with the presence of many important people, but in the following days, the exhibition rooms were empty.

Several articles by prominent Polish art critics have survived. However, given the importance of this exhibition, the reaction seems minimal. This could come as surprise because similar events at the time were commented on much more widely and, additionally, very important works appeared at the exhibition. Ignacy Witz wrote: “It is therefore a major event for us that today in Warsaw we can see Umberto Boccioni’s Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, Gino Severini,’s paintings, the early Carlo Giacomo Balla, the old pictures by the father of Italian Surrealism Giorgio de Chirico, the delicate still lifes by Giorgio Morandi, the characteristic work of [Massimo] Campigli and Enrico Prampolini.”36 Ewa Garztecka added in “Trybuna Ludu”: “You won’t see in Italy what you can see in Warsaw at present : no museum, no gallery has a selection of works so brilliantly characterising the most important stages of Italian art from Futurism to the present day.”37

The fact that the exhibition of Italian art passed without much notice is all the more sad because it was difficult to see works of a similar rank in Poland then. Wojciech Skrodzki commented: “Recognising the exhibition of contemporary Italian art open at Zachęta as one of the most crucial events of the season is not the result of scraping the bottom of the barrel, although I have to admit that the downright disastrous situation with exhibitions of foreign art is a phenomenon of the utmost concern […].”38 The exhibition was also valuable because it was Palma Bucarelli’s own concept: to present half a century of Italian art from the perspective of its contribution to the development of the European avant-garde. Jerzy Olkiewicz, however, pointed out a lack of consistency in this respect, justifying his opinion as follows: “In the first room we see the works of the Futurists, a very beautiful metaphysical painting by de Chirico –next to the pictures of such ‘avant-gardists’ as Campigli, Morandi and [Filippo] de Pisis. Each of these three belongs to the group of seasoned painters of our century – even Campigli – who can bore to death with his female busts. But what avant-garde do we associate them with? The avant-garde of bourgeois taste?”. 39 The critics did not mention the lack of an audience at Zachęta.

Szancerowa, captured in a photograph of the vernissage, does not often appear in other pictures. The materials preserved in Zachęta’s archives from the exhibitions held between 1954 and 1969 are a good reflection of the reality of those times. Szancerowa is present in only a few photographs; the others show men dressed in suits: representatives of the ministry and creative associations. Only a woman with a strong personality and firm party support could hold a similar position in that mal-dominated world.