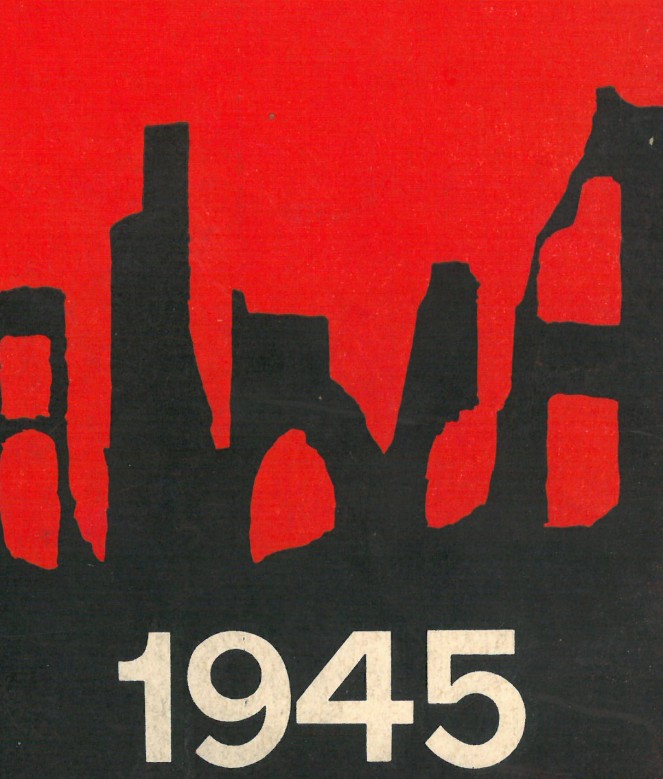

Warsaw 1945 in the photography of Leonard Sempoliński

19.09 – 10.10.1969 Warsaw 1945 in the photography of Leonard Sempoliński

Zachęta Central Bureau of Art Exhibitions (CBWA)

exhibition design: Stanisław Zamecznik

poster design: Stefan Bernaciński

number of works: 135

attendance: 8,525 (Rocznik CBWA [CBWA Annual])

In the 1960s, photography exhibitions organised at the Zachęta Central Bureau of Art Exhibitions were becoming more and more numerous. Between 1968 and 1970, their number amounted to 44 out of the grand total of 143 exhibitions hosted at Zachęta.[1] Photography became particularly useful in the activities of the CBWA’s Field Office Department — for example, 1968 saw as many as 8 photography exhibitions, out of 21 exhibitions organised in total.[2] In some cases, the materials presented in Warsaw or collected on the occasion of Warsaw exhibitions would be abridged to create smaller, ‘travelling’ collections, which would then visit other centres, usually peripheral ones.[3] Thanks to their small size, photographs were very useful for this purpose. Undoubtedly, its information, educational and propaganda potential should not be underestimated.

1969 saw two simultaneous exhibitions, held from 19 September to 10 October. The first was titled 25 Years of the Polish People’s Republic in Photography, while the second was the exhibition in question — Warsaw 1945 in the Photography of Leonard Sempoliński. Both exhibitions were later showcased outside Warsaw and widely commented on in the national papers.[4]

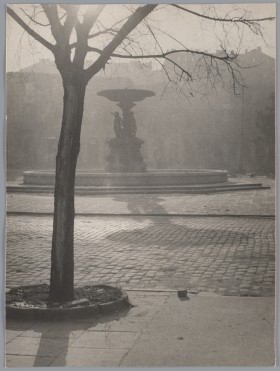

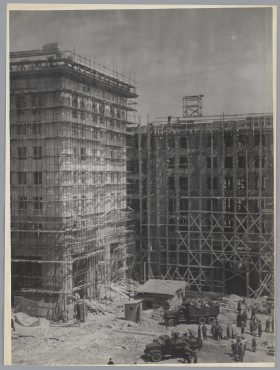

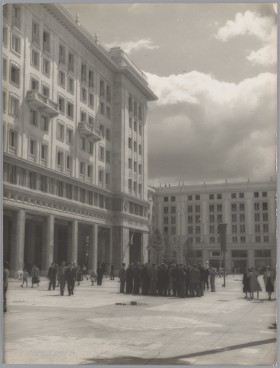

While the first exhibition was an attempt to establish a diverse, optimistic image of the Polish People’s Republic in 1969, carried out mainly using the language of reportage photography, Leonard Sempoliński’s exhibition brought the viewers back to the symbolic ‘starting point’ of the Polish People’s Republic by presenting documentation of the ruins of Warsaw, made shortly after the liberation of the city by the Polish People’s Army and the Red Army. ‘This is the first year of the capital of the Polish People’s Republic’, said Emilia Borecka about these photographs.[5] When leaving the exhibition of Sempoliński’s photographs and entering the space devoted to the 25 years following the war, one could say with emphasis: ‘moving to another Zachęta Hall is like seeing the sun right after the darkness of the night.’[6]

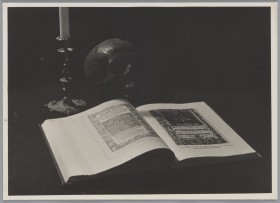

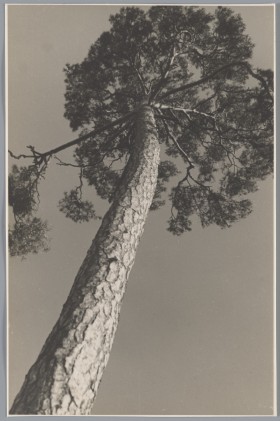

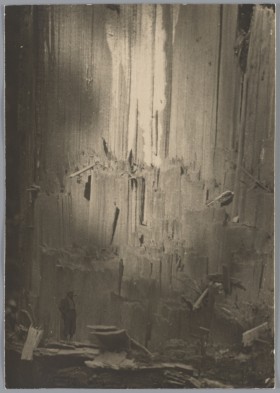

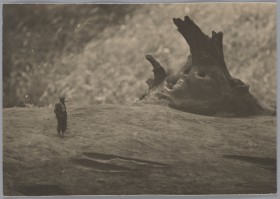

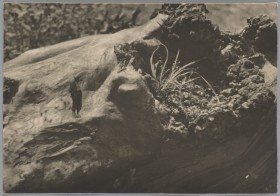

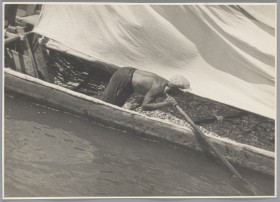

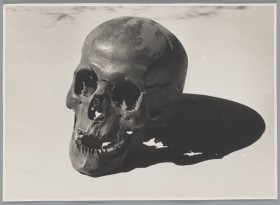

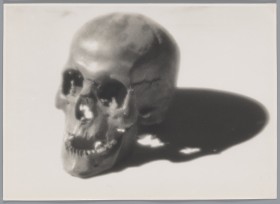

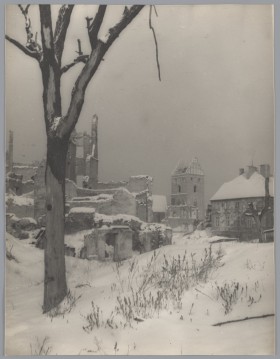

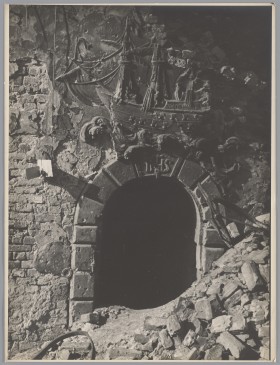

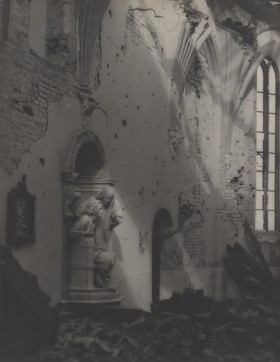

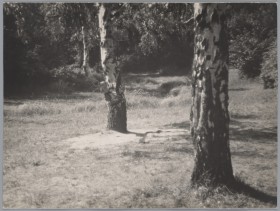

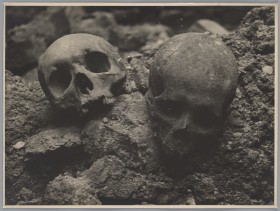

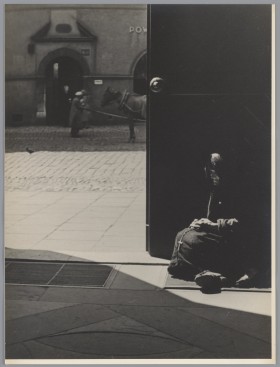

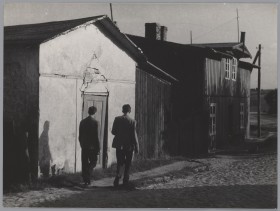

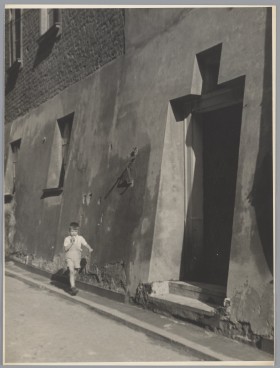

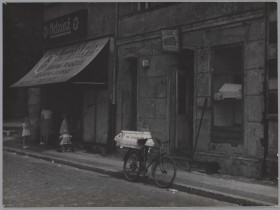

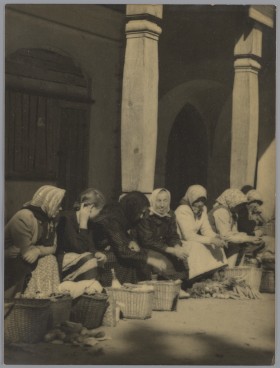

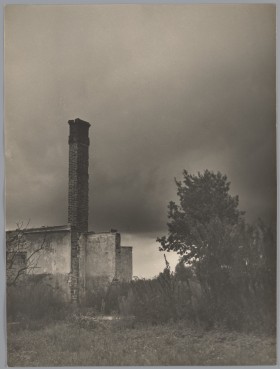

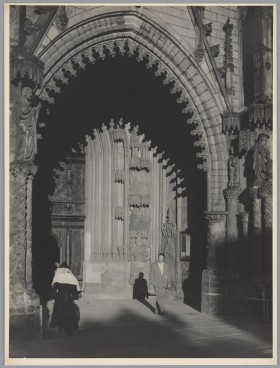

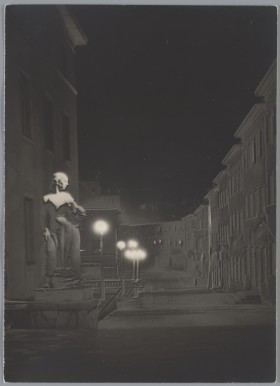

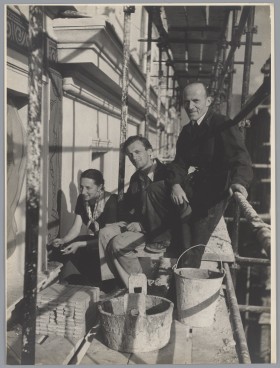

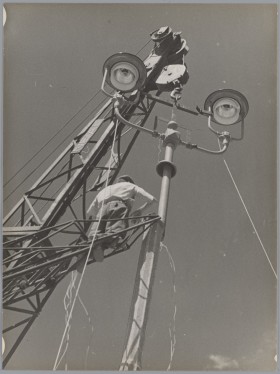

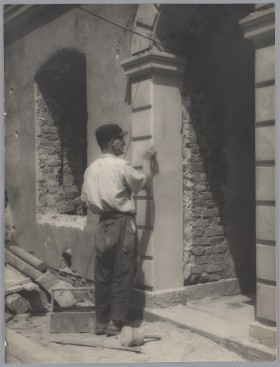

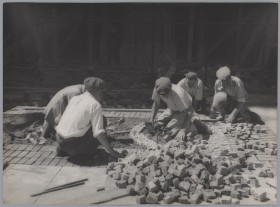

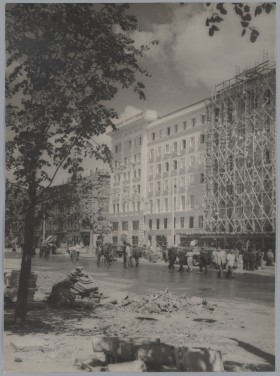

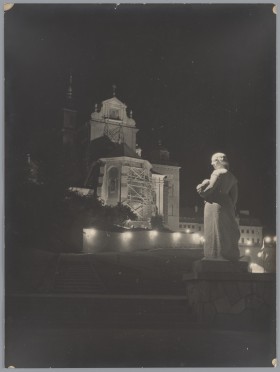

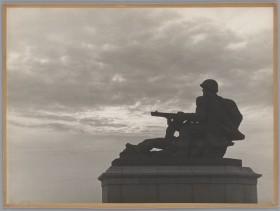

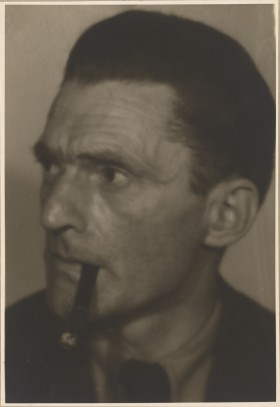

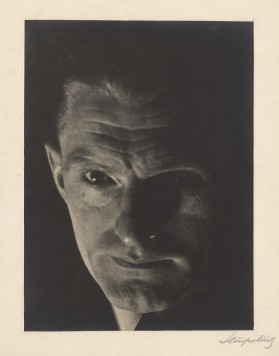

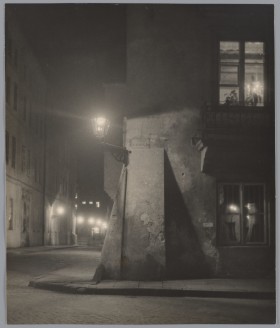

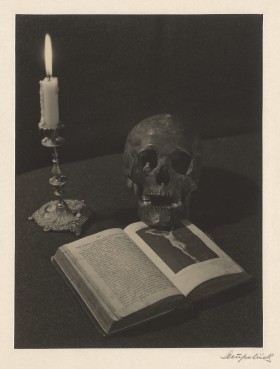

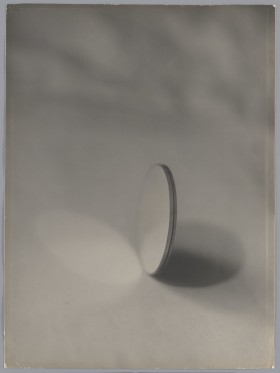

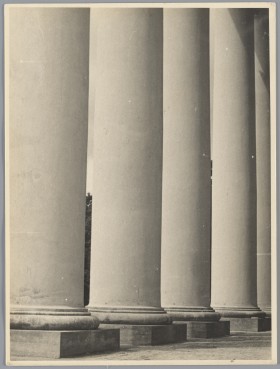

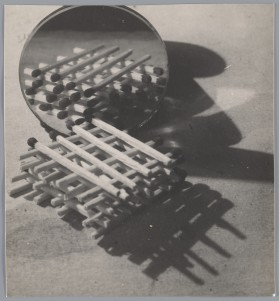

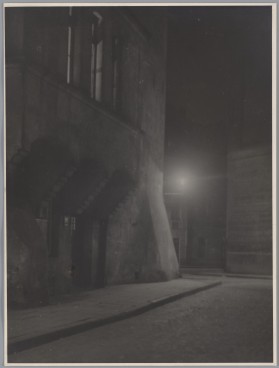

The entirety of the collection of photographs of Warsaw ruins was taken in 1945–1946 by Leonard Sempoliński (1902–1988), who debuted as a photographer just before the war. The collection numbered several hundred photographs.[7] The author was the first photographer who was not embedded with the army to document the ruins of the capital city, starting in January 1945. He would often set off across the Vistula River, but he did not do so on a regular basis.[8] Sempoliński’s collection is distinguished among the vast number of photographs depicting the ruins of Warsaw not only by their early date of creation and scale, but also by the high technical level for that time and a variety of capturing methods. It included a variety of motifs and themes, ‘from panoramas to detail close-ups; . . . from objects as symbolic as the remains of St John’s Cathedral, to the elements of metal fences’.[9] One should not also forget about the documentation of human remains in the burnt-out ruins of townhouses and in field hospitals.

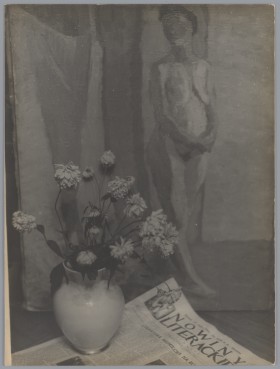

The exhibition at Zachęta featured 135 photographs, which were larger prints specially prepared by the author from copies of negatives. Earlier, photographs of ruins taken by Sempoliński were presented on various occasions at group exhibitions, one of which was probably the famous First Modern Art Exhibition in Kraków, which the photographer participated in thanks to his relations with the ‘modern artists’ circles.[10] It was not until February 1968 that Sempoliński submitted the design of an exhibition of the ruins to the Association of Polish Art Photographers board, receiving a positive response a month later — this also proves the active involvement of the photographer in the shape of the exhibition.[11] After the opening of the exhibition at Zachęta in September 1969, which turned out to be a great success, at last according to press reviews, the collection of photographs of destroyed Warsaw was regularly presented, among others in 1977 in Zagreb and once again in Warsaw in 1984.[12]

In 1975, the album Warszawa 1945 [Warsaw 1945] was released on the initiative of Emilia Borecka,[13] thanks to which Sempoliński’s became even more popular than before, and which also gave it a specific interpretation. The photographs were accompanied by quotations from the press, literature and official documents (lists of exhumed bodies), describing the ambiguous condition of the survivor of the turmoil of war — an experienced participant of the events, who was also a romantic observer. The overall mood of the album is reflected, among others, in the words of Paweł Herz: ‘Why do you cry, traveller of dreams, tourist of ruins, who once journeyed through the dead cemeteries of ancient civilisations? What do you think about when you see the white of human bones peeking from under a destroyed wall? . . .’[14] For decades, the corpus of photographs by Sempoliński was the most famous visual collection of the post-war ruins of Warsaw.[15]

The exhibition at the CBWA placed Sempoliński’s photographs in yet another context, mainly by combining them with the parallel exhibition devoted to the 25th anniversary of the Polish People’s Republic. The press reported: ‘This exhibition is worth seeing, particularly given that there is another contemporary exhibition parallel to it, for which the first serves as the starting point and the backdrop’.[16] Juxtaposition of photographs showing wartime destruction with photographs of places after they were rebuilt, was common practice, used mostly in albums and educational exhibitions, mainly those connected with the anniversaries of the Polish People’s Republic. Even the previously mentioned album by Borecka was initially also supposed to have a similar layout.[17] By doing so, the photographs of the ruins were assigned a propaganda function, because their ‘accusatory’ tone was apparent when they were juxtaposed, further highlighting the optimism of the anniversary narrative.[18] In 1974, the photographer himself justified the need for such juxtapositions, saying: ‘We need to preserve the memory of the tragic times of armed struggle and destruction of the city. However, we need to do it not in order to mourn forevermore, as some tend to claim, nor to hold grudges and foster the urges to exact revenge, because these days it is all about something else. . . . By looking at what we have found, we can better assess our achievements and the extent of work put into building of the new tomorrow thus far.’[19]

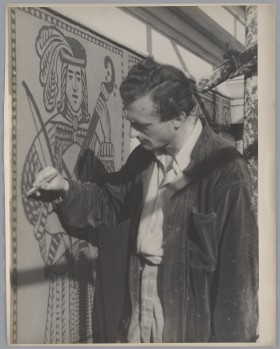

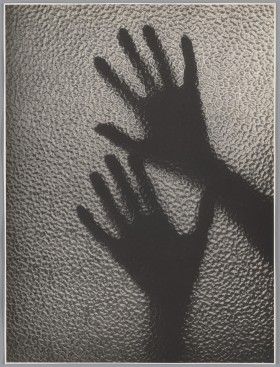

The propaganda appropriation of Sempoliński’s photographs, which were used as a kind of a ‘backdrop’ for the other exhibition, is made even more complicated by the arrangement of the exhibition, designed by Stanisław Zamecznik, one of the leading figures of the modern exhibition industry. Individual prints were put on tall aluminium pulpit-racks,[20] placed relatively densely and evenly in the room, at viewers’ eye level. These structures resembled tombstones, encouraging visitors to move between photographs in a way that resembled walking among the graves. This simple, and yet very sophisticated idea proposed by Zamecznik, who not only elevated, but also invigorated the ruins of the city, gains a new meaning in relation to the ways of depicting the images of the post-war ruins. Graphic artists and painters often resorted to anthropomorphisation (which can be seen in the famous The Stones Are Screaming series by Bronisław Wojciech Linke, also based on photographic studies). A similar device was also used in literature: ‘Some districts had to die in a special way’, Kazimierz Brandys wrote.[21]

Contemporary reviews seem to suggest that the qualities of the arrangement contributed to the overshadowing of the parallel exhibition: ‘The excellent exposition (prepared by Stanisław Zamecznik) elevates and emphasises the message of these documentary photographs. I do not seem to remember another exhibition with such artistic qualities in quite a long time.’[22] This all tells us that Sempoliński’s exhibition, even if it was initially considered to serve as a backdrop of sorts, seemed to be the main exhibition instead. This can be also further evidence by the reprinting of the catalogue text on the first page of the Fotografia monthly — the only magazine in Poland devoted to artistic photography, while the other exhibition of photographs was completely overlooked in the periodical and not mentioned in any way or form.[23] A similar situation could be seen in Przegląd Artystyczny, where the list of the most interesting exhibitions prepared by Anna Trojanowska featured a paragraph devoted to Sempoliński’s exhibition, while there was not a single mention of the exhibition on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the People’s Republic of Poland.[24] One can only make educated guesses regarding the extent of influence of individual elements on the whole situation — the value of the presented photographs, Zamecznik’s spatial arrangement and the propaganda character of the second exhibition, which Wojciech Kiciński described in Trybuna Ludu as a ‘collection of wall bulletins’.[25]

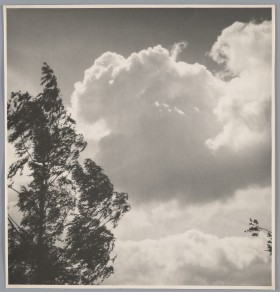

Both the comments in the press, as well as the photographer’s own reflections, reveal yet another ambiguity — it appeared at the moment of stylistic definition of the exhibition and the collected visual material. On the one hand, the photographs were seen as an ‘objective and shocking report’ and ‘documents, the authenticity of which recalls the vivid memories of the horror and cruelty of war’,[26] and the author was said to be driven by the desire to ‘preserve and save the image of the annihilation of the capital’.[27] On the other hand, Sempoliński’s shots were not denied their artistic qualities, which was indirectly pointed out by the photographer himself, who said: ‘I was surprised that the sunlight, which usually makes photographs of architecture more lively, further highlighted the hopeless terror of the ruins. This experience was so strong that while photographing, I tried not only to document individual objects, but also to convey the overall tragic landscape of the dead city and its atmosphere.’[28] Contemporary commenters, who noted that ‘Sempoliński’s . . . exhibition is more than just a documentary’,[29] might have unconsciously pointed to the difficulty of assigning an unambiguous aesthetic category. In the exhibition catalogue, Andrzej Osęka stated that ‘Leonard Sempoliński did not acquire a taste for the poetics of ruins, he did not search for effective themes in this landscape . . . His vision is free from any attempt to falsely enhance its expression . . .’ Further in the text, he added: ‘He was able to wait until the right light at noon or at sunset brought out the shape and its destruction. He perfectly understood the role of the light and the clouds — the only living elements in this immobile and petrified landscape, and he lets us understand it too.’[30] The interpenetration of both aspects was noticed only by Emilia Borecka: ‘Sempoliński does not look for aesthetic qualities in the landscape of the ruined city . . . Nevertheless, his photographs are at an outstanding technical level, and the shots — although perhaps not intentionally — often constitute a perfect artistic and compositional whole.’[31]

The tension between the documentation and artistic functions of photography is a theoretical and methodological problem that remains current to this day. While looking at the exhibition from this perspective, it is worth noting that the commenters raised the importance of a number of contexts, including the historical and — indirectly — propaganda contexts, but also psychological and existential ones — the biographical dimension of the photographs. Sempoliński was a born Varsovian, which is why it can be assumed that his experience of seeing the destruction did not have a lot to do with the attitude of a tourist fascinated by the horror; that he experienced it as an empathetic, but also desperate resident-witness, who tries to accuse the perpetrators of an atrocity.[32] This experience deepened the emotional attitude towards the ‘theme’ and also intensified the ‘surrealism’ of the observed reality, activating both a kind of moral imperative to giving a testimony, as well as distancing the photographer from the paradigm of cold, objective documentation in favour of compulsive, empathetic action: ‘I walked around the places of execution and the rubble, feeling some kind of a strange excitement. I experienced and read the tragedy of Warsaw from every piece of rubble and scrap metal found among the ruins.’[33] The ‘poetics of ruins’, rejected by the contemporary viewers and by the photographer himself, could function based on different principles, not as an attempt to aestheticise the tragedy, or even as a ‘passion’ of a documentary photographer facing the strangeness of the experienced reality, but as a metaphor for the gaze of a modern subject who looks at their own life, and through it at the meanders of history.[34] This aspect is where we should look for the reason for the constant attractiveness of the subject of the ruins of Warsaw, both to viewers and scholars of post-war visual culture.

A slightly abridged version of the exhibition, featuring 123 photographs, was presented in Katowice (Youth Palace; 5 December–28 December 1960; attendance: 1,320). Leonard Sempoliński’s photographs returned to Zachęta with his retrospective exhibition in 2005.

Kamila Leśniak

Institute of Art History of the University of Warsaw

This text was prepared as part of the National Programme for the Development of Humanities of the Polish Minister of Science and Higher Education — research project The History of Exhibitions at Zachęta — Central Bureau of Art Exhibitions in 1949–1970 (no. 0086/NPRH3/H11/82/2016) conducted by the Institute of Art History of the University of Warsaw in collaboration with Zachęta — National Gallery of Art.

Bibliography

Catalogue:

- Warszawa 1945 w fotografii Leonarda Sempolińskiego, exh. cat., introduction: Andrzej Osęka. Warsaw: Związek Polskich Artystów Fotografików, Centralne Biuro Wystaw Artystycznych, 1969

Source texts:

- (ibis). ‘Warszawa, której nie wolno zapomnieć’. Życie Warszawy, no. 235, 1969

- Kiciński, Wojciech. ‘Dokumenty i ilustracje’. Trybuna Ludu, no. 273, 1969, p. 6

- (oe). ‘Obejrzyjcie te wystawy’. Dziennik Ludowy, no. 232, 1969

- Osęka, Andrzej. ‘Warszawa 1945 Leonarda Sempolińskiego’. Fotografia, no. 9, 1969, pp. 194–199

- Trojanowska, Anna. ‘Przegląd galerii warszawskich’. Przegląd Artystyczny, no. 1, 1970, p. 58

Press mentions:

- Dziennik Ludowy, no. 224, 1969

- Dziennik Zachodni, no. 290, 1969

- Express Wieczorny, no. 222, no. 227, no. 235, 1969

- Głos Pracy, no. 224, 1969

- Poglądy, no. 1, 1970

- Trybuna Ludu, no. 259, 1969

- Trybuna Robotnicza, no. 288, 1969

Other source materials:

- Photographs from the exhibition: Stanisław Zamecznik’s family deposit in Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw

[1] In comparison, between 1965 and 1967, out of a grand total of 166 exhibitions organised at the Central Bureau of Art Exhibitions, 22 of them were devoted to photography.

[2] In 1969, the CBWA’s Field Office Department organised a total of three exhibitions, including two exhibitions of photographs.

[3] This is how the Photography Exhibition Commemorating the 25th Anniversary of the Polish People’s Republic, which was probably created out of alternative photographic material, which could be also analogous to the 25 years of the Polish People’s Republic in Photography exhibition opened in September at Zachęta, was disseminated. Both collections were created in June and July of 1969 (marked as ‘collection A’ and ‘collection B’). These exhibitions visited places such as the International Press and Books Club in Lublin, as well as the Sugar Factory Workers’ Hotel in Przeworsk or the Civil Militia Higher Officers’ School in Szczytno. They were displayed as late as January 1971.

[4] Both exhibitions were presented simultaneously in slightly abridged versions — the 25 years of the Polish People’s Republic in Photography exhibition featured only 160 photographs out of the original 220, while Warsaw 1945 . . . included 123 out of 135 photographs — at the Youth Palace in Katowice in December of the same year.

[5] Emilia Borecka, ‘Posłowie’, in Warszawa 1945, Warsaw, 1985, p. 295.

[6] Express Wieczorny, no. 227, 1969.

[7] The exact number of photographs in the collection was never determined — some sources point to the existence of about 1,500 unique photographs, while others indicate that there may be as many as several thousand photographs. A collection of about 500 negatives is held in the Museum of Warsaw, Leonard Sempoliński’s photographs of ruins are also stored in the Department of Iconography of the Institute of Art of the Polish Academy of Sciences (prints from the 1960s, the Department also held the lost photograms presented in 1969 at Zachęta), as well as the Iconographic Collections of the National Library of Poland (first prints from 1945–1946), and the Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź (10 prints made in the 1970s.). Based on Magdalena Wróblewska, ‘Obraz jako dokument, dokument jako obraz. Fotografie Leonarda Sempolińskiego’, in „Robię tylko dokumenty” — fotografie Leonarda Sempolińskiego, Warsaw: Zachęta National Gallery of Art, 2005, pp. 14–22, Borecka, p. 304, Karolina Puchała-Rojek, ‘Uwagi na temat digitalizacji archiwum Leonarda Sempolińskiego’, organizacja.home.pl/projekty/sempolinski/archiwum.php?str=3 (accessed 26 June 2017) and searches conducted by the author in 2009.

[8] The first photographs of the destroyed capital were taken by Czołówka, the Polish Army film team, which entered the city on 17 January 1945. Cf. Wróblewska, p. 15.

[9] Puchała-Rojek.

[10] Karolina Lewandowska, ‘Nowocześni 1948 roku’, in Budowniczowie „Świata Fotografii”, exh. cat., Poznań: Centrum Kultury Zamek, 2009, n.pag.; I Wystawa Sztuki Nowoczesnej. 50 lat później, exh. cat., ed. Józef Chrobak, Marek Świca, Kraków: Galeria Starmach, 2000.

[11] See the calendar in ‘Robię tylko dokumenty” — fotografie Leonarda Sempolińskiego’, p. 31.

[12] Exhibition of Polish photography in Zagreb and Milan (1977), curated by Urszula Czartoryska and 1945 Warsaw exhibition at the Association of Polish Art Photographers (1984). See the calendar in ‘Robię tylko dokumenty” — fotografie Leonarda Sempolińskiego’, p. 31.

[13] Re-released in 1985.

[14] Paweł Herz, ‘Umarłe i żywe’, Życie Literackie, no. 5/6, 1945.

[15] It was not until 2017 that photographs of the ruins of Warsaw (not only those created after the Second World War), taken by other authors, were published separately: Ruins of Warsaw: Photographs from 1915–2016, ed. Łukasz Gorczyca, Michał Kaczyński, Warsaw: Raster Gallery, 2016. Also noteworthy is a documentation of the post-war ruins of Warsaw carried out a few years beforehand by photographers Zofia Chomętowska and Maria Chrząszczowa: The Chroniclers. Zofia Chomętowska, Maria Chrząszczowa. Photographs of Warsaw 1945–1946, ed. Karolina Lewandowska, Warsaw: Archaeology of Photography Foundation, 2011.

[16] (ibis), ‘Warszawa, której nie wolno zapomnieć’, Życie Warszawy, no. 235, 1969.

[17] Wróblewska, p. 22.

[18] The ranks of people who perceived these photographs as ‘accusatory’ included Andrzej Osęka; Andrzej Osęka, ‘Wstęp do katalogu wystawy’, in Warszawa 1945 w fotografii Leonarda Sempolińskiego, exh. cat., Warsaw: Związek Polskich Artystów Fotografików, Centralne Biuro Wystaw Artystycznych, 1969, n.pag.

[19] Leonard Sempoliński, ‘Dlaczego fotografowałem Warszawę?’, in Warszawa 1945, p. 294.

[20] The use of aluminium frames is indicated by Wróblewska, p. 21.

[21] Kazimierz Brandys, Miasto niepokonane, Warsaw, 1946, p. 280.

[22] (ibis).

[23] Andrzej Osęka, ‘Warszawa 1945 Leonarda Sempolińskiego’, Fotografia, no. 9, 1969, pp. 194–199.

[24] Anna Trojanowska, ‘Przegląd galerii warszawskich’, Przegląd Artystyczny, no. 1, 1970, p. 58.

[25] Wojciech Kiciński, ‘Dokumenty i ilustracje’, Trybuna Ludu, no. 273, 1969, p. 6.

[26] Dziennik Ludowy, no. 224, 1969.

[27] Borecka, p. 304.

[28] Sempoliński, p. 292.

[29] (oe), ‘Obejrzyjcie te wystawy’, Dziennik Ludowy, no. 232, 1969.

[30] Osęka, ‘Wstęp do katalogu . . .’.

[31] Borecka, p. 305.

[32] This aspect was noted by Karolina Puchała-Rojek, who followed the reflection of Andrzej Osęka.

[33] Sempoliński, p. 291.

[34] Regarding the image of the ruins and its meaning, see Grażyna Królikiewicz, Terytorium ruin — ruina jako obraz i temat romantyczny, Kraków, 1993; Iwona Kurz, ‘Obraz ruin — obraz świata w ruinach. O tym, co mogą znaczyć gruzowiska’, in Polska fotografia dokumentalna na skrzyżowaniu dyskursów. Materiały z sesji zorganizowanej w dniu 2 IV 2005 z okazji wystawy Leonarda Sempolińskiego, Warsaw: Zachęta National Gallery of Art, 2006, pp. 39–45.

Warsaw 1945 in the photography of Leonard Sempoliński

19.09 – 10.10.1969

Zachęta Central Bureau of Art Exhibitions (CBWA)

pl. Małachowskiego 3, 00-916 Warsaw

See on the map