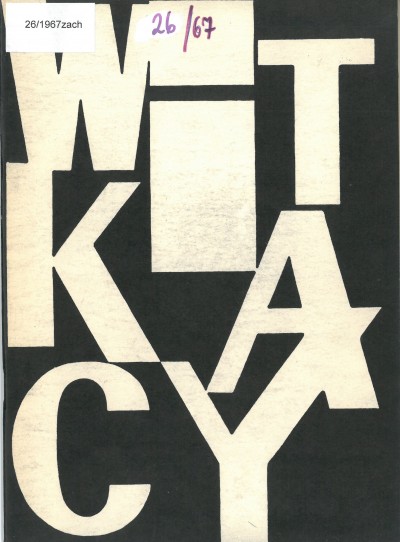

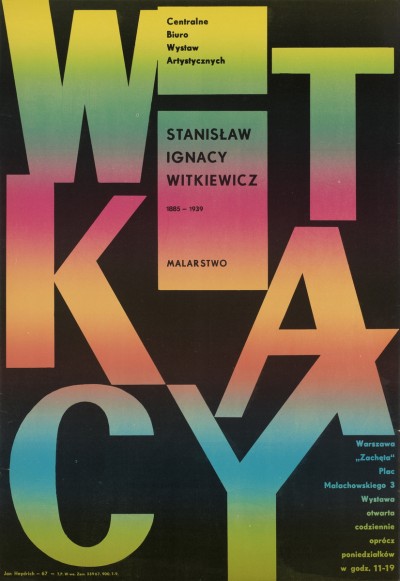

Exhibition of paintings and drawings by Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (1885-1939)

09.10 – 25.10.1967 Exhibition of paintings and drawings by Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (1885-1939)

Zachęta Central Bureau of Art Exhibitions (CBWA)

organiser: CBWA

commissioner: Helena Blum

exhibition design: Tadeusz Kantor

attendance: 18,752

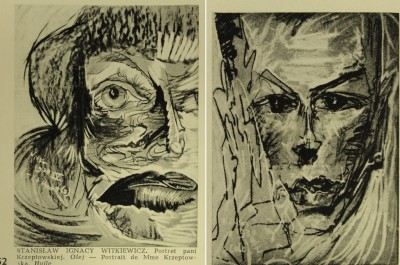

The retrospective exhibition of Stanisław Witkiewicz, also known as Witkacy, which opened at Zachęta on 9 October 1967, featured 130 works by the artist, including 97 paintings and 33 drawings.[1] Among the presented paintings, only 9 oil canvasses were showed alongside 88 pastel works.

Among the most important works absent from the exhibition was not only the famous Self-Portrait from 1913 stored in the National Museum in Warsaw, but also many equally important paintings, such as: The Temptation of St Anthony I, Composition with a Dancer, Marysia and Burek in Ceylon and Fight (Tree Felling).[2] The visitors who came to the exhibition to see some of the artist’s most interesting paintings, such as Australian Landscapes from 1918 or Young Poland landscapes created by the artist in the first decade of the 20th century, did so in vain. Witkacy’s photographic works were also omitted.

The exhibition in question was dominated by portrait works, with 79 portraits, painted mainly in the 1920s and 1930s. It might seem that an exaggerated appreciation of the effects of the activity of the S. I. Witkiewicz Portrait Company was a conscious curatorial action of exhibition commissioner Helena Blum, who in the introduction to the exhibition catalogue emphasised that ‘. . . the problem of the portrait is now more and more pronounced in Witkacy’s paintings’.[3] In the aforementioned catalogue, Blum also decided to take advantage of a very interesting approach to describing Witkacy’s biography through the prism of his portraits. The expressions of appreciation towards pastel portraits painted by Witkacy were accompanied by overlooking paintings, which according to the artist’s intention were intended to fulfil the assumptions of ‘pure form’. Contrary to Helena Blum’s opinion cited above were statements of reviewers who emphasised the higher artistic quality of the works created by Witkacy between 1918 and 1925. Such a position was held by Ignacy Witz and a critic using the pseudonym SAM, among many others.[4]

The exhibition was arranged by Tadeusz Kantor. Judging by the four photographs preserved in the Zachęta archive, the artistic design of the exhibition was hardly spectacular, nor did it use innovative solutions. Witkacy’s works were presented on the walls of exhibition halls and on white panels forming partition walls of sorts. These panels were the basic element organising the exhibition space, adapting the oversized rooms on the first floor of Zachęta for exhibiting the relatively small pastels and sketches. Kantor sought to diversify the size and shape of exhibition spaces, which led him to making one of the exhibition rooms smaller by using tall partitioning panels. In other rooms, he formed small wings and a long hall, which was supposed to be used by the visitors.

The creation of several smaller, independent spaces in the exhibition halls had both positive and negative consequences. On the one hand, it favoured more intimate contact with Witkacy’s compositions, but on the other, it also hampered the efficient flow of people who visited the exhibition in droves.[5] As one might conclude from the preserved photographs, carving out several independent spaces also made it possible to divide the exhibition space into a number of thematic areas. In an intimate, family atmosphere of one of the small wings, three portraits of Włodzimierz and Maria Nawrocki were presented. One could even say that Kantor did so in order to remind the visitors about the context in which the majority of the best portraits painted by Witkacy came into being — created for his friends and families belonging to the intellectual elites during the interwar period in Poland.

The most interesting and innovative arrangement was used for the room where figural compositions from the 1920s and 1930s were presented. The walls were draped with black tapestries, and a corresponding catafalque table was put in the hall, covered with identical fabric. The piece of furniture took up almost the entire space of the room, with the broken surface of the table top standing out. The analysed space was designed to resemble a tomb. It may be assumed that the arrangement designed by Kantor was supposed to symbolise Witkacy’s departure from the assumptions and principles of ‘pure form’ by staging a peculiar burial ceremony in the tomb of metaphysical feelings and emotions.

The authors of press reviews unanimously pointed out the fact that Witkacy’s art, unlike his dramas, did not enjoy universal recognition, arousing conflicting emotions and judgements. They also pointed out that there were no comprehensive and exhaustive monographs presenting Witkacy’s art in a systematic and in-depth manner, as well as the fact that the interest in his art expressed by the broader audiences stemmed mostly from the snobbish and scandalous fame the artist enjoyed throughout the Interbellum. The analysis of press reviews accompanying the exhibition fully confirms the controversial status of Witkacy’s paintings in the 1960s. Apart from literary praise surrounding Witkacy’s works, the press also featured realistic analyses of the shortcomings and issues surrounding his art, as well as articles showing almost a complete lack of understanding of his paintings.

One of the most radical and surprisingly shallow reviews was written by Andrzej Osęka — an outstanding art critic. He believed that ‘Witkacy’s painting does not have but a hint of “pictorial nobleness”, in fact he does not have anything do to with any care for nobleness at all: Witkacy does not care about form, nor does he care about composing his artistic image.’[6] He also emphasised that the form of his works reveals ‘. . . horrid affinities — with caricature, and even with the most trite kind of expressionism’.[7] What is more, he noted that ‘our painters, used to “transposing” the form, believe that Witkacy’s paintings transpose it to an insufficient extent, that the artist only distorted the surface of naturalistic shapes, while he was supposed to move and distort the very structure of figures and faces’.[8] Despite his scathing criticism of the artistic form of Witkacy’s paintings, Osęka believed that they were ‘one of the most shocking statements in the history of Polish art’.[9] The above opinion stemmed from treating works by Stanisław Witkiewicz as a testament to the tragic life of the painter, manifesting itself in the constant anxiety of the ‘convulsive artistic imagination’.[10]

A similar, psychological way of reading Witkacy’s art can be found in a review written by Ignacy Witz, who regarded his paintings with great esteem and saw the signs of ‘the greatest tragedy of contradictions’, ‘tragedy of existence’ and the ‘convulsions of the premonition of death’ in his art.[11] Osęka’s opinions were echoed by Anna Krasińska, who emphasised that ‘Witkacy’s controversial art evokes many arguments and reservations after years, since only a few of his portraits managed to stand the test of time. . . . the majority of works presented at Zachęta are, unfortunately, cheap effects and sick obsessions.’[12] Krasińska’s critical comments, however, were largely directed against the curatorial strategy adopted by Helena Blum, particularly with regard to the inappropriate selection of works presented at the exhibition. It would be impossible not to disagree with Krasińska in this respect, as the choice of Witkacy’s compositions made by the curator left much to be desired. Among the aspects that call for a negative assessment, one should point out the omission of numerous interesting oil paintings from the period when the artist was searching for the artistic incarnation of ‘pure form’, as well as the inclusion of a large number of sketches and pastels characterised by a lower load of expression and lower quality.

Articles written by Ignacy Witz, [Lucjan] Kydryński, SAM and Ewa Garztecka were much more favourable towards Witkiewicz.[13] The most flattering statements came from Kydryński, who believed that ‘the rooms with Witkacy’s paintings are a great hit. Compared to the passion, power, originality and modernity of this kind of art, works by other artists seem to be bland, boring and surprisingly old-fashioned.’[14] He also considered the exhibition in question to be ‘an artistic experience that is both immensely powerful, as well as outstanding in its own regard.’[15]

Witkacy’s pioneering attitude towards surrealism and post-war abstractionism was a separate issue that critics were keen to write about. Jerzy Zanoziński considered Witkiewicz to be a pioneer of surrealism, rightly stressing that treating the painter’s fantastic compositions from 1918–1925 as an anticipation of post-war abstract painting is a misunderstanding.[16] Ewa Garztecka disagreed with Zanoziński, since she believed the artist to be a precursor of artistic automatism, which was the foundation of post-war gestural painting genre.[17] Another critic, who wrote their reviews under a pen name SAM, decided to go with ‘mental automatism’, not referring to the creative methods of post-war abstract expressionism, but to the declared creative ethos of pre-war surrealism.[18] Helena Blum believed otherwise — she rejected the claim that Witkacy’s works were characterised by the features of mental automatism, instead she noted some hints of surrealism in the artist’s work.[19]

The exhibition constituted a part of the broader exhibition policy of the Central Bureau of Art Exhibitions, which organised several dozen anniversary and retrospective exhibitions devoted to the work of artists active during the interwar period throughout the 1950s and 1960s. During these exhibitions, the CBWA presented mainly the pre-war and post-war achievements of living artists, including Bronisław Kopczyński, Stanisław Dybowski, Tadeusz Cieślewski (father), Vlastimil Hofman, Leokadia Bielska-Tworkowska, Jan Cybis, Tymon Niesiołowski, Józef Tom, Zygmunt Radnicki, Aleksander Rafałowski, Emil Krcha, Czesław Rzepiński, Stanisław Szczepański, Jan Hrynkowski, Konstanty Maria Sopoćko and Mieczysław Jurgielewicz. The Bureau also organised a number of posthumous retrospective exhibitions, presenting the art and achievements of the recognised ‘classics of the interwar period’, such as Edmund Bartłomiejczyk, Henryk Kuna, Zygmunt Waliszewski, Henryk Wiciński, Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, Katarzyna Kobro and Władysław Strzemiński. The posthumous retrospective exhibitions also presented works by less-known artists working in the interwar period, including Jerzy Fedkowicz, Jan Golus and Kazimierz Tomorowicz.

Piotr Cyniak

Faculty of Artes Liberales, University of Warsaw

Networked Transdisciplinary Doctoral Studies

This text was prepared as part of the National Programme for the Development of Humanities of the Polish Minister of Science and Higher Education — research project The History of Exhibitions at Zachęta — Central Bureau of Art Exhibitions in 1949–1970 (no. 0086/NPRH3/H11/82/2016) conducted by the Institute of Art History of the University of Warsaw in collaboration with Zachęta — National Gallery of Art.

Bibliography

- A. G. ‘Zabawa kosztem Witkacego’. Życie Warszawy, no. 248, 1967, p. 4

- Dziennik Ludowy, no. 234, 1967

- Express Wieczorny, no. 241, 1967

- Głos Pracy, no. 241, 1967

- Pomorze, no. 21, 1967

- Przekrój, no. 1177, 1967, p. 6

- Tygodnik Kulturalny, no. 43, 1967

- Blum, Helena. [untitled introduction], in Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz 1885–1939. Malarstwo i rysunek 1957, exh. cat. Warsaw: Centralne Biuro Wystaw Artystycznych, 1967, pp. 5–10

- Dragan, Michalina. ‘Wariacje na temat Witkacego’. Dziennik Bałtycki, no. 250, 1967, p. 4

- Florczak, Zbigniew. ‘Firma Witkacy’. Polityka, no. 44, 1967, p. 6

- Garztecka, Ewa. ‘Witkacy — malarz’. Trybuna Ludu, no. 288, 1967, p. 8

- Grubert, Halina. ‘Witkacy i Le Witt na wystawie w Zachęcie’. Express Wieczorny, no. 245, 1967

- HEN. ‘Jesień w galeriach’. Sztandar Młodych, no. 237, 1967, p. 4

- ‘Interesujące ekspozycje w „Zachęcie”’. Słowo Powszechne, no. 235, 1967, p. 3

- Kaczmarski, Janusz. ‘Przegląd galerii warszawskich’. Przegląd Artystyczny, no. 1, 1968,

- p. 54, ill. pp. 52, 66, mention on p. 68

- Krasińska, Anna M. ‘Witkiewicz, Le Vitt i Popielak’. Za i Przeciw, 1967, p. 13

- Kydryński, [Lucjan]. ‘Kurier Warszawski’. „Przekrój”, no. 1178, 1967, pp. 9–10

- Osęka, Andrzej. ‘Witkacy’. Kultura, no. 45, 1967, p. 10

- (PAP). ‘Malarstwo Witkacego na wystawie w „Zachęcie”’. Życie Warszawy, no. 240, 1967, p. 4

- (SAM). ‘Malarstwo S. Witkiewicza’. Słowo Powszechne, no. 266, 1967, p. 3

- Witz, Ignacy. ‘Witkacy i Le Witt w Zachęcie’. Życie Warszawy, no. 247, 1967, p. 3

- Zanoziński, Jerzy. ‘Witkacy 1885–1939’. Przegląd Artystyczny, no. 2, 1968, pp. 20–27

1 The exhibition catalogue listed a total of 183 works; however, 53 works marked with an asterisk were not ultimately included in the exhibition; cf. Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz 1885–1939. Malarstwo i rysunek 1957, exh. cat. Warsaw: Centralne Biuro Wystaw Artystycznych, 1967.

[2] Three of the above-mentioned oil paintings: Self-Portrait, Temptation of St Anthony I and Composition with a Dancer were included in the exhibition catalogue; however, they were not presented during the analysed exhibition; cf. ibid., catalogue numbers: 1, 4 and 21.

[3] Helena Blum, [untitled introduction], in Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz 1885–1939. Malarstwo i rysunek 1957, exh. cat., Warsaw: Centralne Biuro Wystaw Artystycznych, 1967, p. 5.

[4] Ignacy Witz, ‘Witkacy i Le Witt w Zachęcie’, Życie Warszawy, no. 247, 1967, p. 3; (SAM), ‘Malarstwo S. Witkiewicza’, Słowo Powszechne, no. 266, 1967, p. 3.

[5] The fact that the tiny spaces created in selected parts of the exhibition halls lead to overcrowding was pointed out by a number of journalists, including Andrzej Osęka. Cf. Andrzej Osęka, ‘Witkacy’ Kultura, no. 45,1967, p. 10.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Witz, p. 3.

[12] Anna M. Krasińska, ‘Witkiewicz, Le Vitt i Popielak’, Za i Przeciw, 1967, p. 13.

[13] Ewa Garztecka, ‘Witkacy — malarz’, Trybuna Ludu, no. 288, 1967, p. 8.

[14] [Lucjan] Kydryński, ‘Kurier Warszawski’, Przekrój, no. 1178, 1967, p. 9.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Jerzy Zanoziński, ‘Witkacy 1885–1939’, Przegląd Artystyczny, no. 2, 1968, p. 24.

[17] Garztecka, p. 8.

[18] (SAM), p. 3.

[19] Blum, p. 9.

Exhibition of paintings and drawings by Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (1885-1939)

09.10 – 25.10.1967

Zachęta Central Bureau of Art Exhibitions (CBWA)

pl. Małachowskiego 3, 00-916 Warsaw

See on the map