‘ ’ Flight Roman Stańczak

28.04 – 03.07.2022 ‘ ’ Flight Roman Stańczak

Zachęta – National Gallery of Art

curators: Łukasz Mojsak, Łukasz Ronduda

producer of the exhibition at Zachęta: Michał Kubiak

producer of the 2019 exhibition at the Polish Pavilion: Ewa Mielczarek

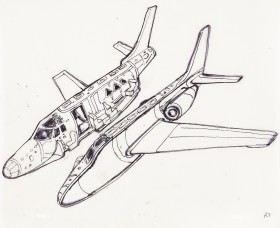

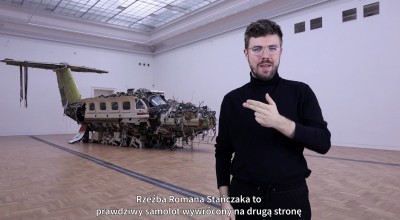

Roman Stańczak’s sculpture is a real aircraft, turned inside out, so that its interior — elements of the cockpit, on-board equipment and passenger seats — becomes visible on the outside, while the wings and fuselage are inside. The artist applied the same strategy of turning things inside out in his works from the Misquic series (in the first half of the 1990s) to everyday objects: a kettle, a bathtub or a wall unit. These works were interpreted in the context of the brutal economic transformation in Poland. Three decades later, the inside-out private luxury aircraft becomes a symbol of global economic inequalities.

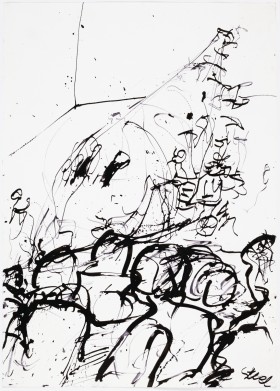

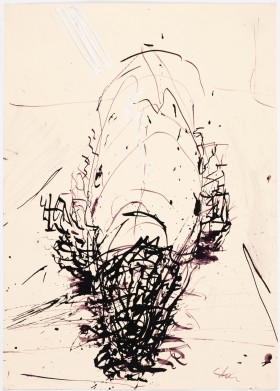

For Stańczak, however, turning things inside out means above all crossing to the ‘other side’ of reality and searching for spirituality in matter, as well as revealing the paradoxes of modernity. The ‘impossible’ change of places between the inside of the aircraft and its outside also brings to mind unexpected and unimaginable catastrophes — situations in which reality collapses. This is what we have witnessed since the first presentation of the sculpture at the Polish Pavilion at the 2019 Venice Art Biennale. The coronavirus pandemic has transformed the way we think about life and death, the relationship between human and non-human entities, the individual and society. Shortly before the new iteration of the Flight exhibition, Russia launched a barbaric invasion of Ukraine. Before our eyes, an unimaginable tragedy is unfolding for the victims of this war, people who are losing their lives, their health and their country. The world is returning to the era of Cold War polarisation, revealing its imperialist violence underpinning.

These are different times, much more ‘interesting’. The grimly ironic title of the 2019 Biennale, ‘May you live in interesting times’, is becoming reality. Flight is also no longer the same sculpture, not only because each display is preceded by the artist’s work with the matter of the piece, giving it a final shape and a different form. It is not the same sculpture because it has acquired new meanings in the meantime, inscribing itself in the transformations, paradoxes and reversals occurring at the foundation of reality. Its message rings even more true today, and the work has clearly shown its disturbing topicality.

Roman Stańczak (born 1969) is a graduate of the famous ‘Kowalnia’, Grzegorz Kowalski’s studio at the Department of Sculpture of the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw. Kowalski was a disciple of Oskar Hansen, the visionary architect behind the Open Form Theory. Aside from Stańczak, other students at ‘Kowalnia’ around the same time included Katarzyna Kozyra, Paweł Althamer, Artur Żmijewski and Jacek Adamas. Stańczak made his debut in the 1990s and his works were created on the margins of the then-forming critical art movement. Between 1994 and 1997, he presented his works at solo exhibitions, after which he consciously disappeared from the art scene. He returned in 2013. As he explains, ‘My sculptures speak of life; not among objects, but among spirits.

Imagining the outcome of the process, initiated by Roman Stańczak, of turning an aircraft inside out posed considerable difficulties. Based on a seemingly straightforward transformation algorithm, the artist’s concept was challenging, if not downright impossible, to visualise. Stańczak himself declared that for him the final result was shrouded in mystery. Thus, from the very beginning, Flight has borne characteristics of an artwork that seeks to convey an unimaginable situation — one that needs to be experienced in order to make any attempts at understanding possible at all. Stańczak’s inside-out aircraft is a piece devoted to unimaginable reversals, extremely rare and often inexplicable events, paradoxes and shocks that shape history and determine the modern-day condition of Europe and the world. It is a monument to the obverses and reverses of reality, which — however difficult it is to imagine — penetrate each other or unexpectedly swap places.

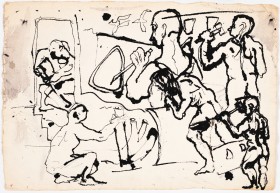

Roman Stańczak’s artistic practice can be seen to express the multi-layered degradation processes experienced in some Polish regions with the advent of capitalism and the country’s entry into the global market at the turn of the 1990s. The neoliberal reforms in Poland — as compared to other Eastern European states — brought about particularly dramatic consequences leading to an exponential increase in income inequality, unemployment rate and the share of population living below the minimum subsistence level.[1] On the rise throughout the 1990s and reaching its peak in the 2000s, the degradation suffered by some social groups adopted a complex character: both material and psychological, social and class-related. Stańczak’s performances and sculptures, with their depictions of ruined bodies and objects, closely correspond to that reality, which for a long time remained outside the scope of interest of Poland’s neoliberal governments and the young generation of artists debuting in the early 1990s.[2]

‘ ’ Flight

Roman Stańczak

28.04 – 03.07.2022

Zachęta – National Gallery of Art

pl. Małachowskiego 3, 00-916 Warsaw

See on the map

Godziny otwarcia:

Tuesday – Sunday 12–8 p.m.

Thursday – free entry

ticket office is open until 7.30 p.m.