Rafał Bujnowski May 2066

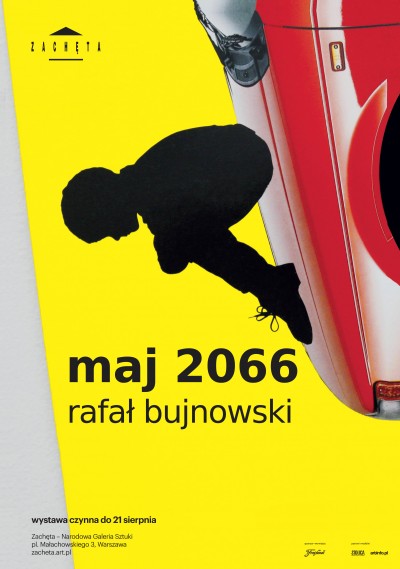

11.06 – 21.08.2016 Rafał Bujnowski May 2066

Zachęta – National Gallery of Art

curator: Maria Brewińska

The exhibition by Rafał Bujnowski is different from his projects to date. It features most recent works only, and highly varied ones, including a video about a man met at a fitness club, a series of paintings from recent months, and two objects — vintage cars — borrowed from the material world of things.

The exhibition at Zachęta may come as a surprise, because Bujnowski is chiefly known as a painter. From the very beginning conceptualising the painting process/practice, it is the picture as a physical object that has preoccupied him. The result of this is a deconstruction of painting, where the artist affirms and processes its key physical elements, while at the same time exposing or revealing them — in the fields both of creation and reception. These elements are the frame (its shape), the paints and pigments, and above all the canvas — the place of ‘action’ or lack thereof — which in its original form should be regarded as prototype to the monochrome. This area holds immense potential — it can give rise to everything or nothing. According to Bujnowski, painting consists in covering the ‘white area’ (the monochrome), in ‘soiling’ the white canvas or paper, which often show through the layers of paint. In an accompanying conversation, the artist explains his understanding of painting. It resonates with those phenomena in art that have in various ways exposed the medium’s illusive nature and objectivity. These threads return in the contemporary practices of artists who repeat creative acts already performed in order to relive or rediscover what is already known.

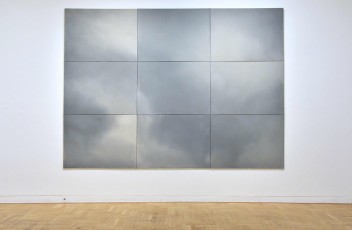

How does the exhibition reflect the process of moving away from paintings, usually treated as fetishes? It presents monochromatic canvases, very recent ones (2016). A series of elegant tondos repeats similar abstract motifs, and in other paintings multiplied images of clouds comprise a monumental, yet illusive, depiction of the sky. Their reception on the representational level seems irrelevant, though. According to the artist, paintings are objects that one can use, can cause to serve another purpose, thus affecting their aesthetic functions. This instrumental approach is an impulse for aging the paintings by about fifty years, using ultraviolet radiation and a chamber for high-temperature material-resilience testing. The paintings acquire slight patina and small imperfections, unnoticeable for an untrained eye, giving them a ‘long stored’ look. This act of aging your own works can be viewed as another step in the escape from illustrativeness and literalness, in the striving to objectify the painting and challenge its exceptional status as a unique and aesthetic object situated between the museum and the art market. Yet painting isn’t so easy to annihilate and doing so isn’t the artist’s purpose.

Bujnowski goes beyond the limits of the medium, reflecting on the phenomenon of time, crucial for the exhibition, which is based on temporal leaps, both forward and back. We see the paintings here and now, but in a condition in which they would be fifty years from now. Hence the show’s title, indicating an instance of discreet futurology — researching the probability and the possible material condition of things. Futurology rests on the premise that future exists only insofar as it is determined by a cause-and-effect chain traceable back to our present.

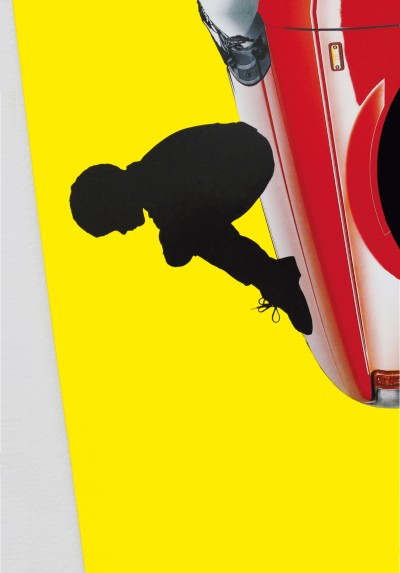

Another temporal jump is documented by a video documenting a 70-year-old man who, thanks to intense training, remains fit as a fifty-year-old. In the artistic perspective, his body, which is the body of a sculptor and art conservator, performs a leap back in time, becoming a living sculpture both reflecting a desire to stop the process of aging and transience.

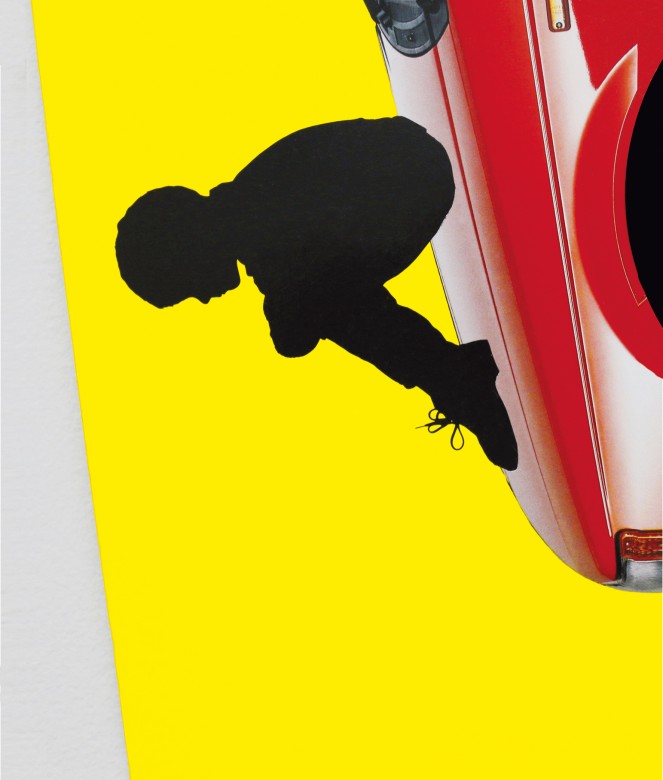

A backwards jump in time is also effected in the exhibition by two randomly selected objects. These are two Mazda cars manufactured in 1986, both perfectly preserved, their impeccable condition taking us thirty years back. Simple, unpretentious, middle-classy, they had been selected from a big bunch of collector’s-quality, more attractive vehicles. Bujnowski seldom uses non-painting objects in his exhibitions. One example was The Last Preserved (2004), where he had made eight copies of the last preserved furniture piece from Karol Wojtyła’s family home, kept at the John Paul II Museum in Wadowice. This time too we are dealing with objects so rare that their presence may seem intriguing. Cars contribute to the construction of the exhibition’s idea, aestheticised by their insertion in the white cube.

Is the show an apology of randomness? The works were indeed selected quite by chance, and the process of the object’s conceptualisation was fast and spontaneous, occurring through the association of situations, events, things. A randomly met man, the random idea of aging the paintings (when the artist had reached for his patina-covered older works), randomly selected cars (when he was looking for a car for himself). Becoming aware of objects’ irresistible presence and temporality, we feel a sense of the randomness of existence. Recurring events reveal certain regularities, constant relations of states and processes, which makes them seem less absurd. A logic of natural processes, based on such cases and on unpredictability, becomes for Bujnowski an artistic method.

The exhibition reflects the relativity of our perception and notion of time. The point isn’t to shoot at clock faces to arrest what we irrevocably lose. The conclusion is always the same: ars longa, vita brevis.

Rafał Bujnowski

May 2066

11.06 – 21.08.2016

Zachęta – National Gallery of Art

pl. Małachowskiego 3, 00-916 Warsaw

See on the map

Godziny otwarcia:

Tuesday – Sunday 12–8 p.m.

Thursday – free entry

ticket office is open until 7.30 p.m.

partner of the exhibition: Institut of Microelectronics and Optoelectronics, Warsaw University of Technology