The practice of Konrad Maciejewicz can be seen as an example of such an approach. With a background in painting and graphics, the artist turned to collages, employing photographs from Polish women’s magazines from the 1960s, 70s, and 80s – he seems equally interested in their imperfect mechanical visuality, as with the air of oddity, or even terror, they evoke. They are far from the adorable retro images made in the recently popular decoupage technique. Maciejewicz – as the artist himself admits – focuses on breaking up the original images in order to combine them into new ones. The compositions of his works are often dense, saturated. It is only on closer inspection that the viewer identifies them as collages. At a glance, they rather resemble painterly works, or, at times – due to their palette resulting from the yellowish colours of papers and weathered photographs – even inlaid wood work, verging on kitsch. It is no accident that such words as ‘individual’ or ‘off’ come to mind in the context of the artist’s practice. Maciejewicz’s works evoke a mixture of curiosity and terror – an effect characteristic of horror films. The viewer descends to increasingly deeper levels of reading: from a general impression of the decorative nature of the whole image, through to painstaking discoveries of metaphors, narratives, and messages hidden in the thick folds of compositions.

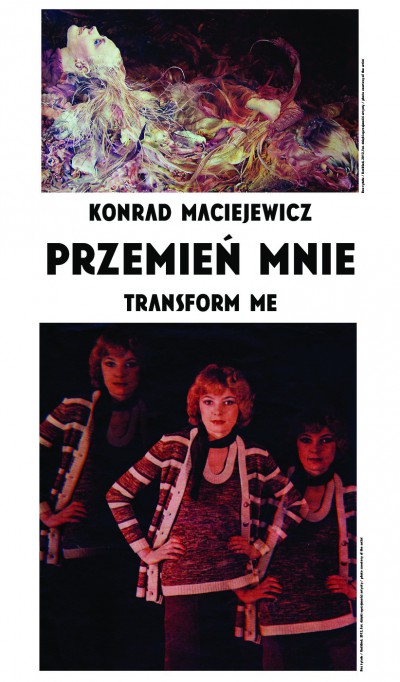

The first individual show of Konrad Maciejewicz, organised last year by Galeria Biała in Lublin, was titled Asylum, and featured a selection of small to mid-size collages in frames. Some of these works are presented in the exhibition Transform Me in the Zachęta Project Room. The text accompanying the Lublin show mentioned strange characters looking for a shelter. While Maciejewicz’s more recent collages form a thematic series relating to the dark side of human sexuality. The artist also admits to mythological inspirations, taking particular interest in themes concerning Aphrodite. His works are populated by groups of characters entering into bizarre, at times cruel, relations. Women tend to play male roles, we encounter motifs of castration and sex change. There are also a great deal of fragmented bodies and entrails – as if in a nightmare, or a gore film. Maciejewicz’s work can be interpreted using existential categories – as a metaphor for the terror of an individual alienated from the world, or an alienated body. Both of these readings are in line with the morose approach to the theme of change in culture that has its roots in the age of Romanticism. It is no longer the antique metamorphosis of the Ovidian hero brought about by the gods, but rather, a metamorphosis that results from extrarational human faculties, along with one’s obsessions, fears, and a sense of a lack of identity. Dostoyevsky, Gogol, Stevenson, Wilde, Kafka, and Schulz – are but a few of the authors who explored this theme of the transformation of an individual in equally gloomy terms.

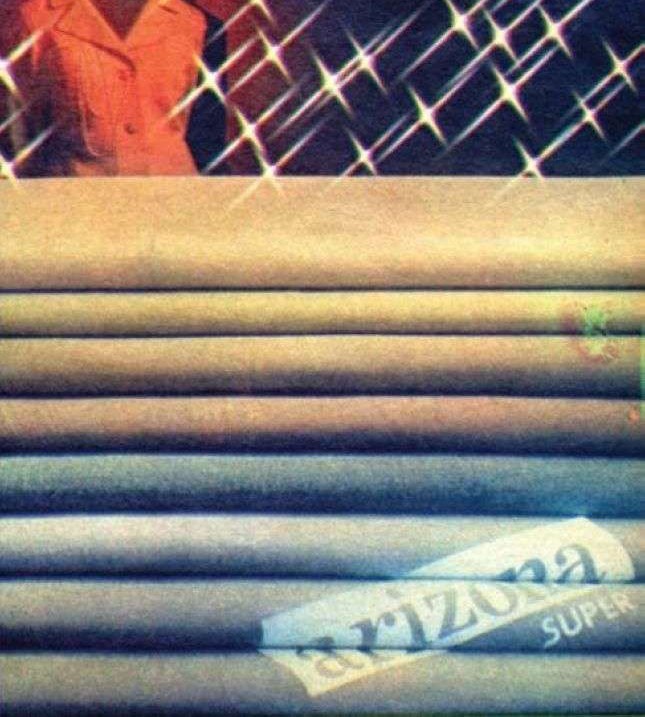

In the exhibition at the Zachęta Project Room, collages are presented alongside lightboxes – Maciejewicz’s most recent project. Once again the starting point for the compositions was images found in old magazines, specifically advertisements from before the consumer age. Seen today, the photographs lack technical perfection, while the advertised socialist goods seem plain and meagre. This, however, is not the essence of the work. Again, after penetrating the surface level, where we recognize a historical anecdote or an amusing clumsiness of primitive marketing, the viewer is confronted with a feeling of discomfort, or even anxiety – something is apparently wrong in these works which emanate an atmosphere of artificiality, or deadness. Extracted from their newspaper context, enlarged and illuminated, the photographs intensify the effect of alienation. The collages and lightboxes brought together in the exhibition Transform Me were deliberately mixed, so as to enter into a dialogue with each other.

Some might be inclined to interpret Maciejewicz’s work within the category of surrealist poetics. The artist, however, dismisses such readings. He comments on the exhibition as follows: ‘The eponymous transformation has a double meaning. The material I use: photographs of garments, dishes from a recipe column, seems animate, imitating the human body. This body, however, is weak, marked with decay, and the desire for change is lined with fear. So this desire carries an undesired effect – it only reveals something crippled and traumatic. The socialist advertisements also begin to exist out of time, creating a parallel universe to that of the collages, where wigs worn by female models and kitschy fabrics become instruments of oppression.’