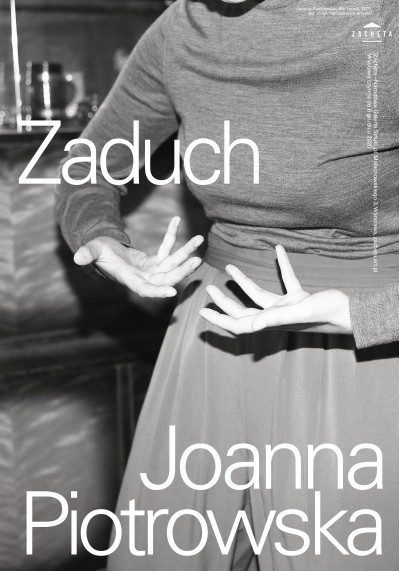

Joanna Piotrowska Frowst

18.09 – 06.12.2020 Joanna Piotrowska Frowst

Zachęta – National Gallery of Art

curator: Magdalena Komornicka

Joanna Piotrowska’s first comprehensive monographic exhibition in Poland presents a selection of her works from the past few years. In her staged photos and videos, the artist focuses on exploring human relationships and their bodily expression. She looks at characters entangled in the context of social institutions, struggling with manifestations of power, emotional dependencies and the violent element of human nature. She is interested in the family, security, home and homelessness, the position of a woman and the psychology and politics of girl rebellion, as well as the human need to control and dominate animals. Her black-and-white, handmade, gelatin silver prints and videos on 16 mm tape are more of a record of performance or spectacle than a documentary.

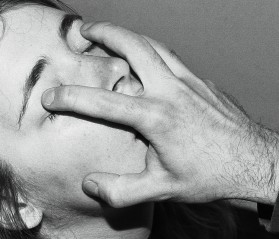

The title of the exhibition was taken from one of Piotrowska’s first photographic series (2013–2014), which brought her international recognition. Frowst (in other words, suffocation, mustiness) brings to mind the dense air of an unaired-out apartment, saturated with complicated family relationships. The series was inspired by the pseudo-scientific, manipulative method of “organising tangled and broken family ties” developed by German psychotherapist Bert Hellinger. Based on the observation of body positions and gestures, the tense, staged photographs showing family systems of dependencies were created.

Visual artist, photographer. She was born in 1985 in Warsaw. She studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow and the Royal College of Art in London. Her works have been presented, among others, at MoMA in New York, at the 10th Berlin Biennale, at Tate Britain in London and at a solo exhibition at Kunsthalle Basel in Switzerland.

Magdalena Komornicka: Why do you photograph zoos?

Joanna Piotrowska: My interest in animal cages is a continuation of the themes that appear in my earlier works — in Frowst, domestic spaces, patterned carpets, curtains, blankets, wall units and cramped rooms act as spatial frameworks for the bodies that inhabit them. This theme crystallises in my later project of ‘shelters’ which presents built in rooms, shrunken-down ‘residential forms’ that are even closer to the body, are even smaller, radically limiting the movements of the household member.

During my visit to the zoo I realised that cages have common features with domestic spaces — they are similarly arranged, there is, for example a bed, i.e. a place to sleep, a corner for eating, doors, corridors, windows, an exit to the garden, sometimes a place to play or, as in the case of monkeys, a place for rest and enrichment, such as a hammock. We design for animals just like we design for ourselves — to provide them with everything they need, according to our ideas about their needs. What’s interesting is what’s common for the space for humans and animals, because it speaks to our responsibility towards other species.

I am interested in designing cages and paddocks for animals because it is a specific architecture of oppression, completely different from, for example, prisons, which are always out of our sight. Cages are a kind of showcase — they serve for a better presentation of the animal; they are the scenery in the centre of which we place the animal like an object. In the case of zoo cages, we are dealing with two very important and at the same time opposing phenomena: protection and responsibility, and enslavement and oppression. This dichotomy is the starting point for most of my works.

MK: Unlike your previous works, these are documentary photos.

JP: Yes. These are the only works where I don’t arrange anything. Everything that is in cages or in the paddocks has already been carefully arranged by someone else. Cages in the zoo are scenery full of well-thought-out props such as a tree trunk, ball, blanket, plate with food, artificial stones or plants. In the Warsaw zoo, there were human clothes lying on the ground in the gorilla paddock. This made a strong impression on me, it made me aware of the proximity of our species.

MK: When we look at a series of photographs from zoos or photographs of objects for animal stimulation, we immediately think of violence or rather power.

JP: You cannot look at zoos without thinking of them as places created for the subordinate Other. The animal-human relationship is an extreme form of the hierarchies we create and brings to mind other forms of inequality functioning in societies — patriarchy in the family, inequality between men and women, racism, etc. Through the joint effort of many people, a huge industry was created for the production and sale of objects designed to allow animals to exist in conditions other than natural ones. It was created so we could observe animals. This evokes some very negative associations for me.

The purpose of some items used to ‘care’ for or stimulate animals is ambiguous. Some, such as toys or mirrors, could be objects for children or, conversely, tools of torture. There’s a grabbing tool that looks like a gun. It is used to hold the animal at a safe distance, a kind of extension of the hand, an object for touching.

MK: This is interesting in the context of your previous works, where there is the theme of touch.

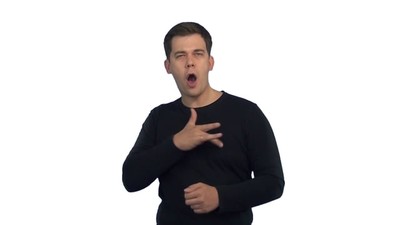

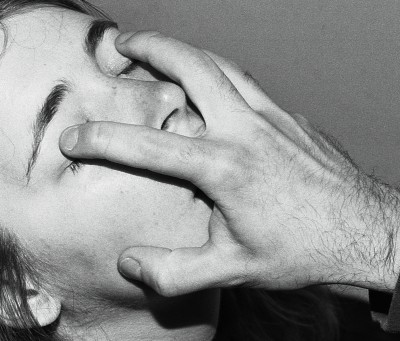

JP: Yes, there’s a theme of touch in many of my works. First in the works from the Frowst series, in the context of intimate family relationships. It is also present in the film showing hands in a therapeutic gesture. Then in subsequent works in the act of physical conflict, self-defence. It is important for me to create such connections and move from animal to human, from human to house, from house to cage, from cage to shelter, safety, intimacy, touch. I circulate between these points of reference, trying to explore the relationships between them.

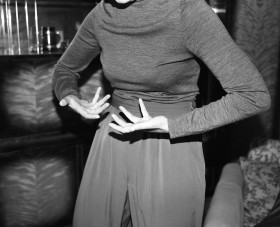

MK: Touch, the body and violence appear in the pictures showing teenage girls in poses taken from the self-defence manual.

JP: That work, like the previous Frowst series, stems from my interest in non-verbal communication and process-oriented psychology. In contrast to classical psychoanalysis, therapeutic techniques based on body work pay attention to gesture and movement. Since the body reacts to things like our private life, emotions and problems, it cannot remain indifferent to our socio-political life. I mean not only the extreme political decisions concerning things like the introduction of a total ban on abortion, but also the stereotypical thinking about upbringing, about how a child should sit, play, use their voice, et cetera. The body, if it is not repressed by imposed conventions, traditions or endless rules, is at best simply ignored. The methods of Moshé Feldenkrais, Alexander Lowen or other similar tools for developing body awareness are still niche, while in my opinion, they should be part of education.

When I came across instructional books for self-defence, I was fascinated by the fact that the body is treated in them as a weapon, and the number of tricks and gestures is a kind of alphabet, an autonomous body language. During that time, I was also reading Joining the Resistance, in which author Carol Gilligan describes how adolescent girls unconsciously self-censor, subordinating themselves to the commonly prevailing patterns of girlhood or femininity in patriarchal culture. Social relations are permeated with male domination, and the categories of attachment and concern characteristic of female psychology give way to paternalism and power. The injustice and inequality that Gilligan writes about exist at many levels, often ‘between worlds’. It seemed interesting to me in the context of the body language of self-defence. The girls and women in my photographs are in domestic spaces, most often in their rooms, and they assume uncomfortable positions. It’s not immediately apparent that these are bodies that are defending themselves. We also don’t see what they’re defending themselves against, we just see that they’re in an intense relationship with something incapacitating, which is outside the frame.

MK: There was also a performance based on this.

JP: First, there were photos, then the film and the performance. The latter is particularly interesting because it involves the audience more directly. In the choreography of the performance, which I initially worked on with Magdalena Ptasznik, I use holds and gestures from self-defence. They are often looped, performed with different strength and frequency; there is also the sound of a tired performer breathing or stamping her leg. Alicja Czyczel, the artist who carried out this performance, modified her movements a bit each time, reacting to the surroundings or the audience. This activity also involves working with the performer’s gaze on the viewer and pointing out sensitive points on the body. This gesture has a very symbolic meaning for me and is impossible to render in a photograph.

The performance is an important part of my artistic practice and appears in most of my projects, even those that are ultimately photographs. A very strong performative element is also present in the project, in which adults build their shelter-hideouts.

MK: Adults building a hideout are playing a children’s game, in which children pretend to be adults, playing house.

JP: Yes, that’s what this project was about. In the act of building the hideout, the shelter, there is, on the one hand, convention and innocence that characterises children’s games, and on the other hand, the seriousness of consciously seeking physical and emotional comfort in adult life. The work is justly associated with homelessness and the basic need of people to have a home and feel safe. It also refers a little bit to materialism and consumerism — to all those things that we have piling up and from which the adults in the pictures build fragile constructions that create an apparent shelter and seemingly give them an identity.

MK: The photographs from the Frowst series, which have already been mentioned, depict people actually related to each other — mother and son, father and daughter, siblings — and are a kind of directed family portraits.

JP: I call them situations. They are staged, some were inspired by the relation of bodies in Hellinger’s constellations, specific gestures, how people set themselves up against each other, where they direct their gaze, and so on. The participants of the classes, according to Bert Hellinger’s method, stand in a closed circle, on a kind of stage where the bodies, just like in self-defence, have their own language built up often from repeated gestures. It was very inspiring for me to see a subtle body language in the context of a method in which history and social conditions are of great importance (by the way, personal stories related to the experience of war appear very often in Hellinger’s constellations). I asked my friends to work with me in creating situations in which they pose with their family members in arrangements partly taken from ‘therapy’ sessions and partly from their own photographs from the past. The result is completely fictitious situations photographed in the documentary convention.

MK: It was difficult for the people in the photos. It turns out that it’s not easy to be close with your loved ones, and that we rarely touch each other. For example, the touch of the daughter and father in your pictures seems ambiguous.

JP: Of course, some positions were not physically comfortable, but sometimes my models surprised me with their naturalness in this unnatural posing. In the case of the picture showing an adult daughter sitting on her father’s lap, I remember the lightness and cheerfulness of posing — the atmosphere was completely different from that emanating from the finished work. Some of the photos bring to mind emotional or physical dysfunction and an inconvenient interdependence. One of the most successful pictures from this series, in my opinion, is associated with the effort of motherhood and childbirth. It shows an adult man lying stiffly next to his mother.

MK: Did watching your family lead you to Bert Hellinger’s family constellations? Or was it the opposite — did observing the choreography of bodies during the constellations initiate this project?

JP: I find family constellations very interesting in discovering the complexity of interpersonal relationships. I was interested in Bert Hellinger before the idea for this series of photos was born. I observed some constellations, I read a lot of books on the subject, I was practically fascinated by this method — mainly because the constellations look a bit like a play. On the one hand, it is a staging, and on the other, real, sometimes very strong emotions appear. The same can be seen when observing family life, because we often rely on patterns of behaviour and take on specific roles — in the role of the caring mother or the provider father, in what is considered to be a traditional Polish family.

MK: Hellinger’s constellations are considered harmful because they are based on manipulation. What is your attitude towards them and does it matter to your work?

JP: I’m not a supporter of this method and I don’t know if I would subject myself to it, but it doesn’t change the fact that certain aspects of the constellations are fascinating to me. This method has something unreasonable, irrational, shamanic. I have always been intellectually drawn towards that which is difficult to understand. This method also makes us look at our current situation from the position of the body and think about the role of past family experience in our lives. I’m curious about this alleged combination of past events with the body here and now. For hundreds of years, shamans in different cultures have talked about such a combination, and this has been the reason for the rituals of encounters with ancestral spirits. These days, we rarely refer to spirituality other than through religion, which is a pity.

MK: What does Frowst mean?

JP: The importance of this title is crucial for the project. It is an interesting word which, in English, serves as both an adjective and a noun. It means mustiness, stuffiness, or suffocation. It’s an impression when we enter a room that hasn’t been aired out for a long time and there’s barely any air to breathe. In my opinion, this can also apply to family relationships. I associate this feeling with the Polish winter, with apartment blocks, where it’s very warm. I have such a childhood memory — curtains, drapes, carpets, wallpaper, a blanket on the couch. It is a memory of cosiness, but also of visual claustrophobia and emotional suffocation. We can use this word in a positive sense — to ‘frowst by the fire’ means to ‘warm up by the fire’.

The photographs from this series have a degree of anxiety, but their overtones are not clearly negative. Two sisters sit, carefree, in the same chair. A brother has his hand on his brother’s shoulder. It’s a gesture of closeness, support, reassurance. I wanted to present these gestures in such a way that their obvious connotations are no longer obvious, to show their hidden meaning and to make them question their own status.

Two women stand close together, tossing a small ball between each other. There. And back. And back again. It looks like there’s no end to this . . . game? It also doesn’t seem to be bringing them much joy. It seems a bit obsessive. Girls, looking at the camera, show different points on their bodies. Instructions? But for what? A young woman sits with her head tilted back; the hands of someone outside of the frame hold up her head; or are they holding it down? Help or violence? What is going on in these photographs and videos and why, even though they are not drastic, are they disquieting?

The cage stayed shut so long

that a bird was hatched insidethe bird stayed still so long

that the cage

corroded by its silence

opened upthe silence lasted so long

that behind the black bars

laughter rang

Tadeusz Różewicz, ‘Śmiech’, trans. Stanisław Barańczak, Clare Cavanagh, in Polish Poetry of the Last Two Decades of Communist Rule: Spoiling Cannibals’ Fun, Chicago: Northwestern University Press, 1991

1. Every day for the last two months, I’ve been approaching these photographs and then backing away quickly. I need some air. It’s hard to breathe near them. Like in an old house of even older people with no one to clean anymore. These prints smell of sickness, medicines, steel, zoos, hay full of manure on a hot, stuffy day.

Joanna Piotrowska

Frowst

18.09 – 06.12.2020

Zachęta – National Gallery of Art

pl. Małachowskiego 3, 00-916 Warsaw

See on the map

Godziny otwarcia:

Tuesday – Sunday 12–8 p.m.

Thursday – free entry

ticket office is open until 7.30 p.m.