No. 12

Reality with Errors

Text by Maria Brewińska

The latest issue of our magazine focuses on Monika Sosnowska, whose exhibition has just opened at Zachęta. Curator Maria Brewińska writes about the artist and her works.

Years ago, in a building in the Ochota district of Warsaw, a residential community celebrated the installation of a railing by the stairs leading to the cellar. Although it was not a great event, the media noted it, writing about the railing that brought the residents together. The simple, welded metal rod anchored in the wall gained importance as an essential element of the building, integrating the community. In terms of design, no railing is like another; those in modernist buildings from the interwar period, as well as those from the 1950s, are wooden, and thus pleasant to the touch thanks to the properties of the material used. They seem to be a trivial detail until we feel their absence or until they fall prey to kitschy renovation. In the spaces of stairwells, they complement the function of the stairs. The rising and falling movement of the rail follows the rhythm of the stair, it seemingly alleviates the height of the storeys. In the geometric grid of divisions of modernist architecture, it fits into the dynamic composition of verticals, diagonals and horizontals — the play between the line and the plane. It is a fluid minimalist ornament that enhances the visual qualities of the designed interior.

Memory evokes here a model of the railings installed in modernist buildings from the 1960s and 70s, constructed en masse throughout Poland, which we still deal with on a daily basis. Their stairwells are equipped with standard oil-painted metal railings, their handrails covered with a colourful material, which is often the only colour accent in the monochrome interiors. In her series of works, Monika Sosnowska refers directly to this architectural detail, a relic of construction from the Polish People’s Republic. The artist became famous for her works inspired by early and post-war modernism in architecture, in which she sometimes refers to iconic designs of the international style, but largely explores the aesthetics and specificity of local architecture. She draws inspiration from the times in which she grew up, and since around 2000, she has been observing and documenting both well-preserved late-modernist buildings and the remnants of architecture built from sub-standard prefabs, which is already falling into disrepair today. This private, but also collective experience of Warsaw in the times of transformation, the chaotic city growing on the ruins of the previous epoch, is enclosed by the artist in her works, which remain in a dynamic dialogue with this past. However, she does so without nostalgia, purifying the process of creation of any affectation. These works, however, activate the memory of unfulfilled utopias of modernity, and the violence of communist power, manifested in architecture and urban planning by the unification of urban tissue and identity.

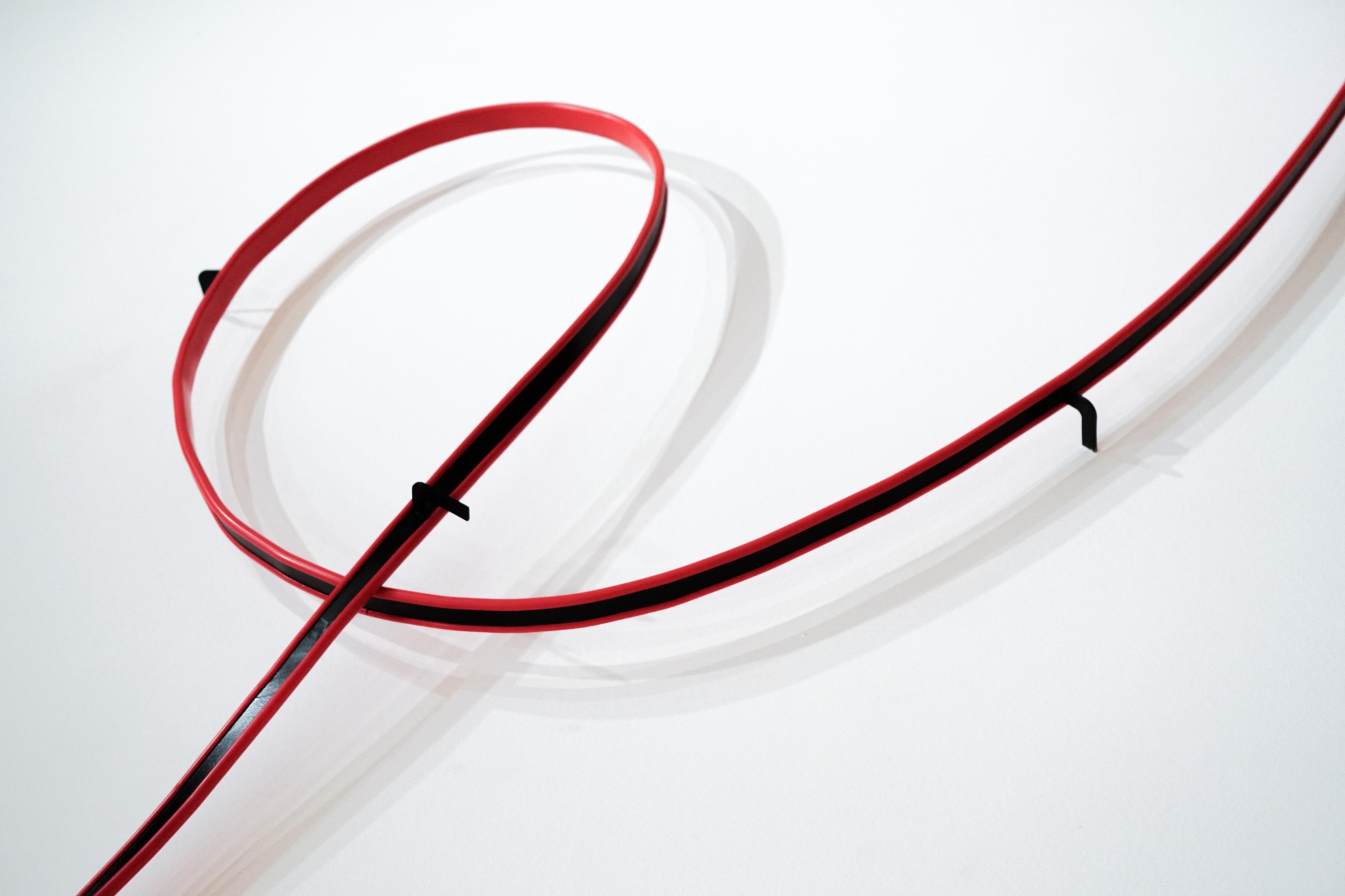

Monika Sosnowska’s oeuvre develops in a series of works drawing on the repertoire of forms and elements of architecture: stairs, façades, balustrades, walls, rooms, construction materials repurposed and then transformed into sculptures, as well as installations bordering on abstraction and figuration. Many of them use the motif of handrails: fragments of black railings hanging on walls, covered with shiny red PVC, free-standing railings with bent balusters or single handrails formed into abstract shapes — precisely made aesthetic objects1. The permanent installation at the Foksal Gallery Foundation building is unique here. The artist used an original balustrade with a blue handrail and added a steel rod to one of the balusters, bent with finesse and stretched in the original space of the staircase from the communist era (Handrail, 2006). As a result, the rigid and concrete materials seem easy to form (twisting, bending, rolling, crushing), which makes some critics write about the organic nature of her works. In fact, the experience of Sosnowska’s works is rather physical, haptic. The works are perceived as objects strongly present in the space thanks to their materiality and subjectivity. In an interview, the artist emphasised the physical nature of the raw materials she uses: ‘When choosing the material, I follow a simple rule: if I make a railing, it is made of what railings are usually made of, that is steel and PVC. I call this “material realism”.’2 She operates in the language of architecture, although she is far from making detailed plans. She begins with simple, handmade models and mock-ups, sometimes drawings, then works with contractors in workshops.

The scale of the works is also important here: the original elements are reproduced in their actual size, which means they may seem too monumental and overwhelming in the exhibition spaces. The theme of the majestic spiral staircase is present in Stairs (2010), presented at K21 Ständehaus in Düsseldorf (2010–2012), a giant structure inspired by a fire escape unique in socialist modernism, an external stairwell in a building on the Zatrasie housing estate in Warsaw’s Żoliborz district. In a smaller version of this sculpture — Stairs (2010) shown at the Herzliya Museum of Contemporary Art in Tel Aviv, as well as at the New Sculpture? exhibition at Zachęta (2012) — the experience of materiality and scale is overshadowed by a sense of irrationality, caused by deformations that disturb functionality. The staircase has sunk under its own weight, as though the steel used to make it began to melt, and this deformation has been underlined by the graceful line of the red railing.

The narrative of the exhibition at Zachęta begins in the representative stairwell of the building — with a steel handrail made of red PVC (Handrail, 2016–2020) intertwined with the existing railing. It runs along the wall, penetrates into the Matejko Room, where it is coiled up on one of the walls at different heights. This is an example of the appropriation, but also the recycling of modernist elements, activities present in many works of the artist. The exhibition takes place in the old part of Zachęta, built in an eclectic style with neo-classical décor. All the works enter into a specific dialogue with the exhibition space but are not stylistically connected with it. The common element may be the understanding of matter as a carrier of historicity; as a result of mutual confrontation, the historicising forms establish a discreet dialogue with the modernist ones.

The exhibition of Sosnowska’s works in the rooms of Zachęta emphasises the clash of two opposing attitudes in architecture: the academic art of the Zachęta building meets minimalist modernity. If, according to architect Tom Emerson3, Sosnowska’s works reflect a potential failure of architecture and the subconscious fears of the architect, then on the level of concrete realisation in the exhibition space they pose a threat to the space that accepts them. Francesco Bonami made a similar remark about the expansive, appropriating works: ‘Sosnowska creates a sculpture with the rapacity to pierce the ceiling and the museum’s boundaries, imposing its presence beyond its natural limitations. But, as in most of her work, it also contains the antidote to avarice, which is failure and collapse’.4 Zachęta’s edifice came out unscathed from the clash with Sosnowska’s works and measured up to their imposing presence. The expansive, monumental curtain-like Façade (2016), borrowed from a typical frame-construction building, occupies the Matejko Room. This gigantic steel skeleton is distorted by the use of powerful forces and stresses to which other works of the artist are also subjected, using materials and technologies typical of the former modernist breakthrough in architecture. The impression of gigantomania accompanying some of Sosnowska’s works comes from testing the material in a series of many brutal, controlled trials. Tower (2014), inspired by the modernist Lake Shore Drive Apartments designed by Mies van der Rohe (1948–1951), Exercises in Construction. Bending (2020) in the Garage, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow, referring to one of Vladimir Shukhov’s towers, and 1 : 1 in the Polish Pavilion at the 52nd Venice Biennale of Art (2007) exceed the size of objects usually presented in exhibition spaces, but are placed there as defeated constructions using materials and technologies developed by engineers to achieve durability. Fall, ruin, degradation, error — these words describe Sosnowska’s objects and at the same time the state of preservation of many modernist realisations from the previous epoch. Market (2013), suspended in the Narutowicz Room at Zachęta, expands the typologies of the space the artist is interested in: the work recreates makeshift constructions of the former stalls from the Europa Fair at the 10th Anniversary Stadium in Warsaw — suspended from the ceiling, the conglomerate of their skeletons turns into an anonymous abstract tangle illustrating social transformation resulting from political conditions.

In many of her works, the artist explores the durability of the original raw materials of contemporary architecture and construction. In these explorations, she does not reference the history of architecture or sculpture, although the overall work fits into various traditions: constructivism, minimalism, conceptualism or radical transformations in sculpture made by such artists as Robert Morris, Richard Serra, Gordon Matta-Clark and Charlotte Posenske, and constitutes new artistic values in the field of architecturisation of sculpture. Sosnowska’s actions on architecture and its materials are interesting for architects themselves. In 2007, she collaborated with Christian Kerez on the Loop installation at the Kunstmuseum Lichtenstein in Vaduz; her exhibition Structural Exercises at Hauser & Wirth London and the one present at the Garage in Moscow were critically interpreted by the already mentioned Tom Emerson. Experiments with steel bending — ‘structural exercises’ — in T (2017–2020), a T-profile bent into a right angle, or in Pipe (2020), which weighed more than a tonne, cut open with a blowtorch and rolled up like a piece of paper — are the result of the study of basic, structural steel architectural elements undergoing transformation and destruction. In a way, they show the forces invisible in the direct experience of architecture. Similar issues are present in the Cross Brace series (2019), which arose from a fascination with the engineering architecture of the eminent creator of industrial structures, Vladimir Shukhov, who worked on designs since the end of the 19th century in Russia and later in the Soviet Union. The steel sculptures look almost stretched to the limit, subjected to stresses and forces they were never tested with. As a result, the cross-braces (elements connecting the trusses), in which the internal logic of construction was replaced by extreme dysfunctionality, look like stretched rubber. The collection in one space of several works made of deformed bars or bars in combination with cocoons made of untreated concrete can be referred to a structural failure, a cataclysm that rips architecture apart along with its steel and concrete roots, but also to the construction innards, usually invisible. The dismantling and combination of elements in the latest works, as if revealing the foundations, is a reference to the architecture in Bangladesh, where, apart from modernism in its local version, a chaotic building reality functions, and where — despite the loosening of rational construction principles — everything somehow works. These sculptures introduce a fascinating material context of another world, a pandemonium of unexpected shapes, but also references to social and political values contained in urban tissue.

In fact, all of Sosnowska’s works are based on the visual archive created by the artist over the last two decades. The monumental, brutalistic, painted metal sculptures, reproducing façades, stairs, railings with handrails, lamps, door handles and structural elements, refer to the rationalism of architecture, whose logic is questioned and transformed. The result is functionless objects, unrestrained by the resistance of the raw material used, but also evoking the fiction and utopia of the avant-garde. The consequence of such actions is the impression of plasticity of matter and the illusion of its lightness.

Among Sosnowska’s works referring to post-war standardised concrete blocks of flats we find references to spatial modules: rooms, hallways with their typical appearance (oil-painted bottom halves of walls, wallpapers). The works depicting interiors (multiplied rooms or even their labyrinths) with a designated functional minimum (as in the blocks of flats) have undergone a metamorphosis, starting with Little Alice (Centre for Contemporary Art Ujazdowski Castle, 2001), Hallway (Venice Biennale of Art, 2003), Tired Room (Sigmund Freud Museum, Vienna, 2005), characterised by fairy-tale illusory traits, optical manipulations or transposition of the idea of unconsciousness into constructed space. The series of interiors entitled Antechamber (2011–2020) is more austere, but it still evokes slightly psychedelic feelings, introducing chaos and uncertainty. Antechamber at Zachęta annexes two rooms, it is squeezed into them; constructed of tall, wallpapered walls on the plan of a star with irregular arms with sharp angles, it disturbs reality. In this abstract space, the wallpaper with a dense floral pattern is a familiar element. The work bears psychological traces of enclosure, an imposed order of limited space, a certain alienation. Two entrances to the installation assume increased performativity of the viewer, while the unbuilt fragments of external walls show the construction: profiles, plasterboards. Here, the spell is broken, we come back to reality. Everything is designed, slightly hyper-realistic, but it does not pretend to be a real object. Most of Sosnowska’s works are, in a sense, unmarked by emotions, except for one — a typical aluminium handle for a door in a block of flats (Handle, 2020). It is distinguished by the imprint of Sosnowska’s hand and fingerprints, like an attempt to transform a mass-produced object into a unique, to give it individual features.

The architecture of Monika Sosnowska’s sculptures is based on elements borrowed from the language of architecture and construction, processed in an unprecedented way. Her works suggest a potential ‘failure of the architecture’, they refer to reality with errors, bringing out things that the architects who in principle design permanent objects to outlive us all, are subconsciously afraid of.

1 See Monika Sosnowska, exh. cat., Aspen Art Museum, Aspen Art Press 2013.

2 ‘Przestrzeń wyrzeźbiona w skali 1 : 1’, Jakub Banasiak talks with Monika Sosnowska, 10.09.2008, krytykant.com/archiwum/przestrzen_wyrzezbiona_w_skali_11__rozmowa_z_monika_sosnowska/ (accessed 20.07.2020).

3 Tom Emerson and Mark Rappolt about Monika Sosnowska at the Monika Sosnowska. Structural Exercises exhibition, Hauser & Wirth, London, 23.01.2018, youtube.com/watch (accessed 20.07.2020).

4 Francesco Bonami, ‘The Cabinet of Dr. Sosnowska’, Parkett, no. 91, 2012, p. 34.