No. 4

May 2066

Rafał Bujnowski Talks to Maria Brewińska

11.06.2016

New issue of the magazine, and a new topic – time. In 2016, during the exhibition 2066, Maria Brewińska asked Rafał Bujnowski, among other things, about midlife crisis, maturity and, of course, painting.

We meet at a special moment in your life, known as the mid-life crisis. You’re in your forties, in your prime, though a bit neurotic.

But in good form.

Absolutely. I’d like you to comment on your maturity. I’m asking because I’ve been through it before, with Piotr Uklański and his exhibition, Czterdzieści i cztery [Forty and four]. You’re another artist that I’m working with who is in his prime, though also in midlife crisis.

And in a few other crises too.

Did you feel mature before growing older than Jesus or after?

After, of course. I guess it has to do with mental stabilisation. But I don’t think it was a single event, like in the movies: bang, and suddenly everything looks different. It’s a process, a stratification rather than an explosion or impressive plot twist.

One consequence of the crises you’re experiencing is your going to the gym and caring for yourself. Another is a film about Włodek, a man you met there. Centred around his body, surprisingly fit given his age, the film is being made specially for the exhibition. I mention this because working on your show means going through a plexus of artistic and existential circumstances.

I met Włodek at one of those places where people exercise to the accompaniment of merry music. My psychiatrist sent me there. But if you’re asking about how things are, we last talked by the Forum Hotel, a ‘historic monument’ from the 1970s turned into a big cafe. And one of the statements in that discussion was that now is the worst time for us, artists born in the 1970s.

Why?

Because we’re in a kind of transition period, a period when you’re unwilling, or unable, to call yourself a ‘classic’, but no longer able to call yourself a ‘debutant’. It’s a rather crucial moment when anything can yet happen, when everything can yet collapse because you’ve piled up so much of it that the balance is precarious. But you can also build a solid foundation on it. The two unused thirty-year-old Mazdas that, I’ll somewhat cheekily admit, we’re putting in the gallery without any intervention whatsoever, can serve as a fitting metaphor of the awkward sense of suspension. These cars are not classics yet, but you can hardly call them recent.

Something may have collapsed in your personal life, but professionally it’s been a stabilisation.

Yes, and a series of experiences. But I still have the idiotic sense, or perhaps a not entirely unjustified sense of embarrassment, that here you have a 42-year-old white man who, crouching or kneeling, stains white sheets of canvas and paper.

Stains?

In the sense of painting, drawing . . . For I still carry in myself, and even try to cultivate, simple emotions, simple definitions of painting or drawing, that this staining of a white, unblemished piece of canvas or paper makes sense.

That’s your job.

And luckily so. The kind of thinking that I’m talking about allows me to rationalise my curious profession, even if I don’t think I’d like to turn completely professional. But wait, we were talking about maturing . . .

About maturity and being in your forties.

Let’s conclude the subject then: I’ll return to the moment when I became a man. It was when I managed to evade aesthetic banality, find my own language. You can call yourself a grown-up when you speak about your own affairs using your own language. At art school, we all painted in a similar fashion, because that was the easy, nice and pleasant thing to do. In the evening you painted what you had for breakfast.

You broke away from such painting style as part of the Ładnie collective through a risky, and radical, gesture — the destruction of painting by moving away from the stereotypical pretty picture that in Western culture is identified with representational art. In fact, from the very beginning your painting philosophy has been truly radical. And consistent.

Perhaps this is the reason of my negation, or doubts, of wondering why you paint, why a grown-up man should spend time staining white canvases. I’ve never done it for commercial reasons. In fact, when I’d dropped out of architecture school and started studying art, there was no art market to speak of. I had no business plan at all. Complete spontaneity. To this day I believe that painting is a curious activity and that every successful painting arises from such self-doubt.

Until ca 2004 you painted objects, ads, works inspired by what you’d had for breakfast. Then came maturity, your own language, challenging the image.

From the very beginning I felt a sense of discomfort with regard to representation and depiction in oil painting. It felt wrong that you could suddenly separate depiction from the picture. Hence these paintings-as-objects: it’s hard to separate the painted object from the object that is the painting itself. This kind of dichotomy has been characteristic for my paintings to this day — they are both pictures and objects.

You began to struggle with white canvas, eventually abandoning colour on behalf of white, grey, and black.

It was a process, without any sudden decisions or about-faces. The path, I believe, with all its mistakes and fluffs, is what matters. In my case, it’s not done in leaps and bounds. Each successive painting, each successive attempt, was a justification for the next one. The end of each work is the beginning of another. And I hope the process keeps powering itself this way. I’ve managed to push this terribly heavy cart quite far. To this rather gloomy, monochromatic niche.

I like the fact that you don’t look at the painting as an object of adoration.

A fetish.

For you it’s always an object. But I have a problem with the small formats of your works. In the larger ones, the materiality vanishes, the surface and what is painted on it becoming more pronounced. What prevails here is our habituation to the ‘smooth’ picture, our customary blurring of its physicality, materiality.

And thickness, the third dimension, disappears?

Yes. You don’t see the frame, the stretched canvas, the irregularities and bumps . . .

Perhaps. But I like the material aspect of the painting. To this day I make canvas stretchers for myself using a woodworking machine. I’ve talked about it somewhere before, actually delighting in the statement that I don’t do it accidentally or out of frugality, but out of the satisfaction of making the picture from start to finish. There are no intermediaries. I myself choose the size and thickness, stretch the canvas, and then fill it.

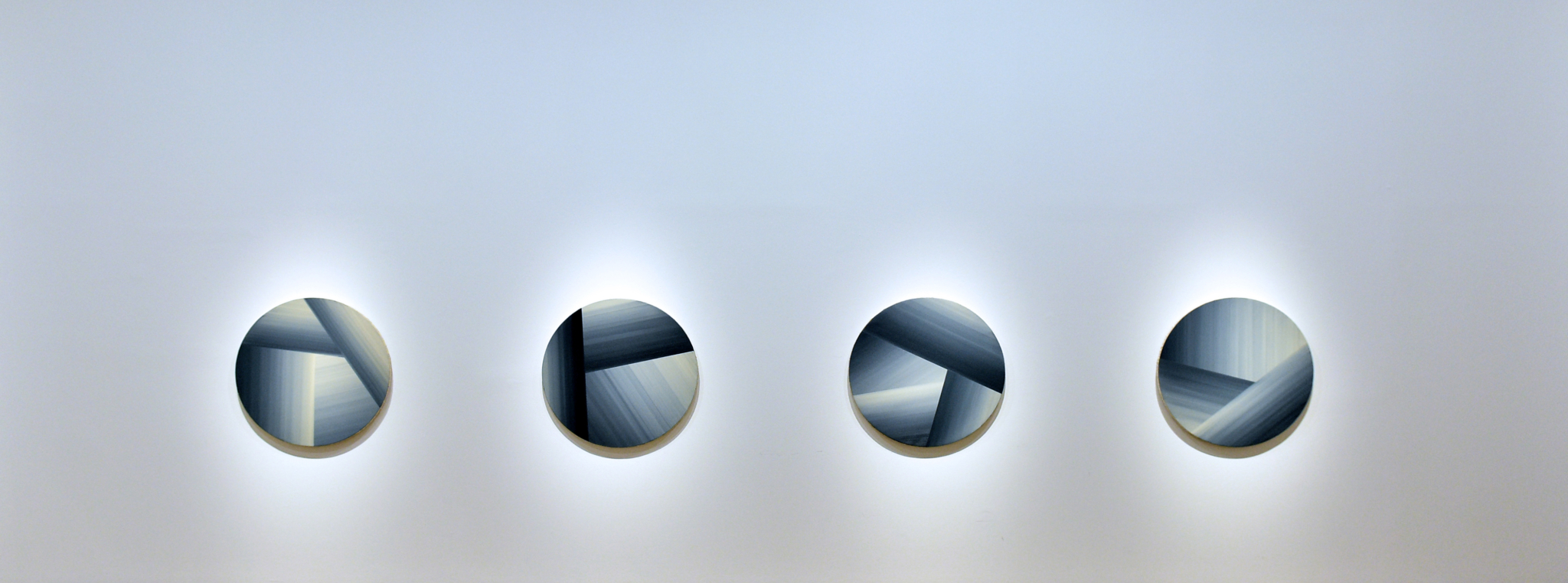

I love the white tondos you order. The frames of your paintings aren’t always straight.

Tondos require superb skill and professional machinery. After making one or two hundred stretcher bars, with satisfaction, of course, I started wondering why I always arrange the profiles precisely at a 90-degree angle. Why are we so accustomed to the right angle? Why not use the shape, form, of the picture as another means of expression besides colour, outline, texture? In my computer, these paintings are called ‘broken pictures’.

Such as Bamboos.

They’re crooked, damaged. Deformed by a fictional force, the energy of an image of a growing plant, the force of nature.

Thus the painting becomes flexible.

Had I done it in a rectangle, there wouldn’t have been enough dynamism in the object. Not even in the picture itself, but in the object. The bamboo shoot would have been dead. It’s better when a growing stalk is painted on a wobbly, ‘damaged’ medium. In each painting there are only two right angles so that the whole thing doesn’t ‘fall apart’. If I were to make a smart-alecky comment, I’d say that first there is chaos and intuition, and only then you perform a rational correction, never the other way round. It has to be a combination of thinking and feeling, or even intuition, because feeling is something that has to do with urges and romancing.

You often multiply your works, e.g. The Whistler’s Mother Painting (2003), ten versions of which are in the Zachęta collection, but altogether you’ve made several dozen. And a very interesting video documenting their automatic painting. You are very skilful in painting virtually identical pictures. You’ve borrowed the picture from an existing painting, James McNeill Whistler’s Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1, whose title actually brings to mind the colours of your works. How did you find it?

I don’t remember. But I liked the picture-within-a-picture because it was painted in a light, casual and contemporary manner, as opposed to the preening face, the headscarf, the drapery. I achieved the lightness through multiplication, thus avoiding the burden and responsibility involved in making a single unique work. A painting, when you intend to make it in a hundred copies, requires such automatism that will produce an effect of lightness, technological skilfulness and routine.

In this way you challenge the very essence of painting — the idea of a singular picture. You still make series of virtually identical works.

It wasn’t my motivation though . . . Of course, this aspect is highly political and topical, and there’s many a coffee-house table it could be discussed at. But the piece by Whistler is marked by a lightness of the ground combined with a contemporary brush stroke, all that in juxtaposition with a figure polished up to suit critics’ or patrons’ expectations . . . This kind of nonchalance is also present in parts of the background in the Old Masters, where, after painting the Jesus, Mary, bishop or general, they allow themselves to experiment a bit, to fiddle with form. Or in the finish of some fragment of nature. Even in old paintings, which I see in various collections around the world, the third ground is more interesting than the first. You can see the painter had more breathing space. Multiplying offers this comfort and quality too.

The painting in Whistler’s painting is monochromatic. At some point you switched to monochromatism and it makes your work stand out. White, grey, black — these are completely different formal values.

I think my paintings are beyond colour. It’s a conscious choice. I’m sensitive to colours, but there is no need for them in my paintings, they would have been one value too many. Besides, there is so much visual value and space to exploit between black and white . . . You can communicate a great deal of information with that.

The monochromatism, and the self-referentiality of many of your paintings, requires a different kind of reception from the viewer.

Sure, and that makes my work a niche thing. Colour is the simplest and most effective emotional medium — yellow stimulates, blue makes you dreamy.

A low-key colour scheme, figurativeness, but few people . . .

If people appear sometimes, it’s as a generic painting element. There’s the landscape, so there are also people. I’ve painted figures on the edge of water, but it’s more like playing with convention, winking at the viewer. You’re right: these are not real, living characters. They are a prop rather than a plot culmination. They’re certainly not as utterly two-dimensional and intellectually distilled as, for example, Malevich’s Square. They do connect with life in a way. I wouldn’t be giving people dry screeds on painting. In fact, I wouldn’t like to be a painter who makes poor people feel awkward.

You produce paintings lacking depth, illusiveness . . .

Illusiveness? But my painting is very showy. Really flamboyant.

Partly so, as necessitated by your method. To me everything you do appears to be about painting, about canvas and paint.

About the curious practice.

Your radicalism is unique. These are not entirely mimetic paintings. Rather it’s a work on painting itself, or about it.

I’d rather not cultivate a sense of exceptionality. There’s only one guy collecting Grolsch beer caps in Poland. Does that make his collection culturally significant? No, it doesn’t.

But there are many painters.

I definitely want to do more than just generate a bizarre kind of discharge. This isn’t a strategy or a recipe for cultural participation, that you have to do something bizarre in order to gain visibility. No, it’s a result of a process and the several dozen or hundred examples that I’ve analysed and drawn conclusions from.

I’m not thinking about your practice in terms of a cultural gimmick, because you’ve developed the language yourself. Rather I’m comparing you to artists who dealt with painting, drawing, in a similar way. In 1953, for example, Robert Rauschenberg purchased a drawing by Willem de Kooning and erased it with a rubber, turning somebody else’s work into his own.

This is about appropriation?

About appropriation with authorial consent. But it’s a highly radical act. Rauschenberg created a monochromatic work, directly transgressing the principle of representation. He destroyed the representation, discovering the clean surface. The same happens in your case. Knowing what Rauschenberg did, I understand better your love for clean canvas, for yellowed sheets of paper that represent nothing. For the original monochromes.

It’s a beautiful work, a beautiful and contrarious gesture. One that reinvests the sheet of paper with its innate potential. One that also serves, perhaps, as a malicious comment on artistic stardom and the crude commercialisation of art.

Rauschenberg actually revealed something that de Kooning’s drawing had obscured. Such situations also happen in your painting and drawing.

For example, in my wire drawings. The sheet of paper is not entirely ‘damaged’ in them. Even the parts left empty are active, shining with the light of white paper. Drawing delicately violates its infiniteness.

But you’ve also done many monochromes covered evenly with paint.

Abstract ones? I’ve had several of those.

Already Bricks were paintings-as-objects, but also monochromes. The monochrome is like a wall. What quality were you pursuing in the video Zug. St. Michael, where you painted over the image of a church? It was excellent — a transition from representational painting to the monochrome.

There are two shades of the same colour there. But the painting process, when filmed, comes across as highly spectacular: the insolence of painting over the canvas, staining it. The video also shows that you can finish the picture at any time — that was the purpose of the experiment. Each additional cloud or brushstroke could have ended it.

But the final outcome was a black surface.

Indeed. I deliberately didn’t finish that painting. I didn’t stop at the so called right moment that is, basically, any moment preceding the completely black canvas.

Your paintings are pretty much about monochromatism. It’s work on the painting medium itself, self-referential. David Batchelor once presented a lecture called In Bed with Monochromatism at the Muzeum Sztuki Łodź. What you’re in bed with are not multicolour landscapes or aestheticised nudes, but white-and-grey-and-black paintings. To me it’s the key indicator of your work.

But it’s not something I’ve planned or contemplated. It’s simply better this way. If these paintings had been in colour, they would have been simply bad, not to the point. Vulgar.

That’s why they’re appealing in a different way. The uniqueness of your art is that — let me repeat myself — you transgress the principles of painting.

You mean depiction itself?

Yes. Because the representational, mimetic, function used to be the main principle of the Western painting tradition. But it’s no longer so since Malevich, Rodchenko, Strzemiński, Klein, Newman, or Rothko.

This door has already been pried open.

That’s why what you do — even if there’s no door to pry open — acquires such significance. A painting, a canvas, that shows nothing becomes an artwork.

Not even becomes, but we begin to perceive it this way. Avant-garde artists have pushed the limits of art’s definition. It can now begin beyond, or even in defiance of, depiction.

At the beginning were three paintings by Alexander Rodchenko. For him, it was the unmasking of painting. Your practice too, I believe, leads to such baring of the painting act.

To conscious spoiling? In both life and the studio?

Yes. They reveal the fraudulent nature of painting. This exposition is phenomenal.

While in Prague recently, I saw a small piece by Henri Matisse. A painting we all know from poor reproductions; one of those that have become so staple, all-too-familiar. It’s truly moving to confront the original, its soul-stirring materiality, the fact that it’s a few grams of paint applied by a shaky human hand.

You unmask painting in such a way that it’s only by convention or due to illusion that we perceive shapes in a clump of black paint, and a fragment of the sky in a broad patch of blue. The monochrome shows that this is a delusion, that we only see paint, in which we’d like to discern a still life, some scattered apples . . .

That’s nice. So all the images are already in our heads and it only takes a small gesture to activate them.

It’s also the viewer’s gesture.

Yes, because the clichés already exist in their heads and all they need is a substitute of the expected. The landscape means there is a horizon, a light colour above, a dark one below. This means that depiction is conventional and trivial. We fell safe when we get something expected, anticipated.

Going beyond that was thought to spell the end of art, but it didn’t. And it returns all the time, also through your paintings. There is no end.

It’s interesting what you say because as an artist I’ve always lived in a neurotic fear of the end, of each project becoming the last one. It turns out, as I said, that the end of one work becomes the beginning of another. But my professionalism is still haunted by the spectre of loss of profession and exhaustion of resources, although today it looks like I can still dig deeper and deeper, that it’s not the end of the work. Do you know why I’ve been so reluctant so speak about this practice as a profession? Because from the very beginning it’s been poisoned with a sense of decline, a feeling that this is already the (beginning of the) end.

In your case, the ‘end of painting’ combines with a frequently felt sense of a demise of the painting profession. In fact, there’s one more word that fits what you do: deconstruction. It doesn’t mean destruction, but a new order, constructing by doing unorthodox things.

Perhaps that’s because I don’t know the orthodoxy, it wasn’t taught to me at art school. I didn’t do a course in painting technology, I had to adapt technology to my own needs, and to my own capabilities. Which happened, and happens to this day, in a random fashion, by trial and error. I was looking for a used car for myself, and found two unique ones. I went to the gym and met Włodek. Some time ago I was trying to give my studio a ‘cleanup’, throw out the old unsuccessful paintings and drawings, but I didn’t, because over time they’ve acquired a patina. And so this fetishistic patina, a weakness for it, yielded a desire to age freshly painted things.