No. 37

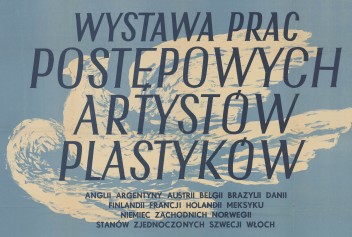

POV: the first (and last) exhibition at the Zachęta

18.07.2022

Michalina Sablik

Social media have recently witnessed a TikTok trend of recording funnyfilms from the perspective of a person’s point of view and their experiences. I do not suppose my text will be equally amusing, but I would like to begin by specifying my own POV. What you are about to read is a subjective selection of artistic phenomena in the field of so-called young art that have emerged during the last few years. I writethis as a participant of exhibitions and events, co-organiser of events, half of the Dzidy duo, and a bit of a critic and curator. I mainly concentrate on grassroots galleries set up by artists, art on the Internet and what counters it –a renewed interest in materiality, old techniques, and nostalgic aesthetics. I also write about post-art, activismand creating new spaces for various minorities, including queers.

Responsibility and ferment, or the grassroots gallery movement

One of the most interesting phenomena in young art is the movement of grassroots galleries, artist-run-spaces and artistic collectives. Its unprecedented scale was showcased by the exhibition All of Poland. The Journey to the Source of Art (Non-Institutional Art Spaces in Poland at the BWA Wrocław in 2020. Pop-up galleries emerge in a specific context set by limited access to professional exhibition venues, crisis of state institutions, aggravated by consecutive lockdowns and what Wiktoria Kozioł defined as a ‘conservative turn’1. On the other hand, online presence offers underground venues and collectives a chance to quickly gain visibility and constantly expand their audiences. Artists have understood that collective activities in a group with a specific name, aesthetics, and social media account may attract the interest of gallerists and curators. Artist-run-spaces are set up in all Polish cities and boost the diversity of the field of art. They are oriented to young artists, experimentation, organising performative and music events. They frequently occupy sheds, garages, basements, private rooms, clubs, academies. They often have no permanent seats and their exhibitions last only a few days. These entities are ephemeral, based on the energies of their founders, collective (often unpaid) work, and ideas. They disappear as quickly as they appear – due to burnout, lack of funds, or the engagement of their organisers in other projects. They seldom seek to establish more stable structures or enter the art market. BWA Drewniana, DOMIE, o/b/c/y, Galeria Czwartek, Galeria Śmierć Frajerom, Galeria Naga, Jak Zapomnieć, Galeria Piana, Turnusik and Serce Człowieka are just a few initiatives of this sort.

1 Wiktoria Kozioł, Homary, Gołębie, Jastrzębie. Zwrot konserwatywny w sztuce polskiej „Magazyn Szum” 2021, nr 34, s. 46–71.

An emblematic example of such activity were the galleries set up by Kamil Pierwszy and Kamil #2in his room in the district of Mokotów in Warsaw, operating alternately as Serce Człowieka and Śmierć Człowieka. They corresponded to two distinct artistic and life pathsof the artist-curator: his humanistic interests and those focussed on futurology and posthumanism. Once every few weeks, Kamil removed all the furniture from his room and organised an exhibition. Those were initially attended by a handful of friends, but after a few monthsit became possible to meet the most prominent cultural journalists and institution directors in his kitchen.Each time, he managed to arrange that modestly sized space differently. He single-handedly created the documentation, which was often published in international art magazines. He also soon began participating in the Warsaw Gallery Weekend and organising shows in other spaces. The pandemic and tribulations of renting the flat sent him on the lookout for a new place. For two years, his galleries were hosted by the Nowy Świat Muzyki venue in the very centre of Warsaw. The beginning of this year saw the last exhibition there, since the municipal authorities decided to raise the rent and make the space available for a more ‘profitable’ business: a bar run by celebrities.

Kamil calls himself a headhunter and, indeed, he is excellent at picking young talent. His gallery hosted some of the first exhibitions by Joanna Woś, Zosia Pałucha, Ada Zielińska, Konrad Żukowski, Marta Niedbał, Krzysztof Grzybacz, Jakub Gliński, among other figures. Many of them later made it to the rosters of private galleries in Poland and Europe, which tapped into Kamil’s research. At some point, he attempted to ‘capitalise’ on his activity and started representing a group of artists and himself. He entered the art market at a good moment, in the pandemic year of 2021, when everything was selling like hot cakes, and he achieved major success with hispresence at the Basel art fair. He went there with a group of artists,involved in the installation and supervision of their own exhibition. I remember from their social media stories that instead of endorsing themselves at boring standing parties, they bathed in the Rhine and basked in the sun.

Kamil quickly entered the art market and soon withdrew from it. He announced a hiatus in the gallery’s activity. This took many by surprise, especially after such roaring success, but it was also sad because it coincided with the information about right-wing directors taking overart institutions one by one, the cancellation of the Hestia Artistic Journey competition, thetermination of theViews – Deutsche Bank Award, and the fiasco of the Project Room at the Centre for Contemporary Art Ujazdowski Castle in Warsaw.

Kamil’s decision undoubtedly resulted from his character and system of values. The art world wanted to imposed itsrules on him, which he refused. He now wants to focus on his own work in the field of post-photography, graphic art, sculpture and goldsmithing. We have had an opportunity to work together and I must admit that Kamil is a true visionary, with a passion and outstanding imagination, who has always been a few steps ahead of current discussions in art. I can sense that he still has not had his last word and will soon surprise us.

Artists-avatars, or let the graphics cards burn

The pandemic and lockdown sent many cultural and social activities to the Internet, sealing the merge of the online and offline reality. Legacy Russell opposed the dichotomy between online and IRL (in real life) with the term‘away from keyboard’, believing that it was no longer possible to be offline. Huge media companies (Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Snapchat, Twitter) redefine the future of visual culture by imposing their interfaces and ideologised tools serving the visual representation of ourselves and reality. Russell’s essay describes artists who generate errors and glitches in the system. The author highlights the revolutionary potential of activities that tap into digital tools to criticise and make visible the ‘non-transparency’ and ideologisation of the Internet. Examples of such approaches can also be found in young Polish art.

It is hard to be an artist nowadays without a social media account, above all on Instagram, which, as a medium focussed on visuality, has become a vital source of information about the art world. Artists quickly changed their funny nicknames to the ‘name.surname’ format. Instagram Stories allow for following work in the studio on a daily basis. It is essentially no longer necessary to get out of your bed to see whole exhibitions just minutes after they open and feel like you are there at the opening thanks to short videos.The art market has been similarly stirred up, once closely guarded by gallerists – ‘gatekeepers’. Documentation of exhibitions enjoys an ever greater importance, and it often defines the very process of their creation. A show must look good in photographs published by online magazines, such as Ofluxo, Art Viewer, KubaParis, and AQNB. It is also expected to be ‘insta-friendly’ and include features that encourage taking selfies.

Returning to artists, however, they themselves have become avatars, merging with their online representations. Many of them make a conscious use of it as part of their artistic practices. Their feed becomes a permanent performance, which features not only their carefully curated images, but also inspirations, manifestos, works by other artists. Photos of cats are remixed with political or activistic posts and reproductions of works, which compels the understanding of the latter through the prism of an entire identity constructed online. Artists who consciously tap into the potential of the Internet include Sebulec, Franek Warzywa, Weronika Wysocka, and Isla Paradis.

One of the more interesting avatars is WetMeWild – a figure created by the visual artist Justyna Górowska:a hybrid of a Slavic nymph, a mermaid and a cybernetic woman from the future. Górowska has been developing her Instagram project since her artistic residency in New York in 2017. She took an interest in underground watercourses in Manhattan, which were used as ‘natural’ sites to build the metro. She chose the Spring station, where she performed by dressing up as a Berehynia with wet hair, leaving stickers with information and marine scents in various places on the metro. Górowska ‘hacked’ various elements of reality (metro station name, bottled water logo), tapping into the augmented reality technology. Scanning the code revealed warnings about water contamination or the harmfulness of microplastic. She also staged animated conversations with the nymph, which initially drew people in like a sex chat in order to gravitate later to topics concerning ecology. Alongside the curator Ania Batko, the artist created the most interesting exhibition in virtual space. Originsbrought togetherseemingly distant topics, such as criticism of racism, pre-war Constructivism, the Polish avant-garde, or an Instagramfilter for changing the appearance of the face. WetMeWild is also active in theRiver Sisters collective and is a permanent guest of Flow, an artistic residency on the Vistula River. In 2021, alongside Ewelina Jarosz, Annie Sprinkle and Beth Stephens, she staged a cybernetic, eco-sexual wedding to the brine shrimp from the Great Salt Lake near Robert Smithson’s famed Land Art installation. Augmented reality allowed for experiencing intimate contact with one of the oldest species inhabiting the lake.

2 Legacy Russell, Glitch Feminism. A Manifesto, Verso, London–New York 2020, s. 5.

Górowska’s practice combines numerous media: performance, film, photography, fashion, choreography. She harnesses a broad array of aesthetics: Slavdom, Instagram culture, corporate aesthetics, exclusive modern interiors, online sex portals. This collage of symbols builds the WetMeWild figure, sending out a distinctive eco-feminist and rebellious message.

Artists-avatars are also the Eternal Engine duo: Jagoda Wójtowicz and Marta Nawrot. They describe themselves as cybernetic witches, digital fairies in techno culture, and cyberfeminists. The variety of the media they use is impressive: from 3D design, to films, animations, VJ projects, performances, 3D printedsculptures, to electronic music production, poetry, games and virtual reality experiences. Their works are characterised by a post-internet, digital aesthetics based on shiny, sharp and tribal ornamentation, elements derived from early fantasy games and various interfaces. The featured forms are inspired by organic microorganisms: cells, fungi, insects and bacteria, as well as their technological counterparts, i.e. nanotechnology. The artists address a broad range of topics: from deep fakes and fake news,to the criticism of surveillance capitalism, cyber futurism, to life in the metaverse.

Eternal Engine are becoming specialists in remixing various orders as well as in humour and poetry composed using technological neologisms. In the film Proposal for Public Television: DEEP NEWS, they act as television hostesses from the future, reading out generative headings in which information about the climate disaster is mixed with sensational local news and fantastical events. Emerging from their antics is a vision of a new medievalworld, in which cyber-peasants fight, but instead of villages, they burn graphics cards and Polish national servers.

Important arguments concerning contemporary Internet culture were put forward by Natalia Sielewicz in her lectureFrom Burning Man to Magic Meme. Techno-Paganism in an Era of Culture Wars. Sielewicz remarks that in a polarised world that finds expression on the Internet both sides or tribes refer to paganism, magic as well as beliefs, narratives and aesthetics bringing to mindmedieval and pre-scientific times.These threads and aesthetics are eagerly addressed by young Internet artists. Aside from them, there are avatars of artists, such as WetMeWild, who adopt hybrid forms, queer reality, draw attention to potential new forms of existence. Artists-avatars have a defined political agenda, championing (eco)feminism, open access to data and technology, criticising surveillance capitalism, challenging the ‘transparency’ of the Internet.

3 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lceMDPMX3yI, dostęp. 7.07.2022.

4 Natalia Sielewicz, Od Burning Mana po magic mema. Techno-pogaństwo w czasach wojen kulturowych, „Magazyn Szum”, 28.01.2022, https://magazynszum.pl/od-burning-mana-po-magic-mema-techno-poganstwo-w-czasach-wojen-kulturowych/, dostęp: 18.06.2022.

In the time of sickness I want to dance the hardest

When I moved to Warsaw in 2017, the filmAll these Sleepless Nights was hitting the cinemas – a ‘portrait of a generation’, awarded at numerous festivals. A somewhat pretentious movie with a simple plot, and yet a good portrait of Warsaw’s nightlife with its outdoor raves and house parties. One of the protagonists was played by Krzysztof Bagiński, an artist and DJ, co-founder of the Kem collective, now a resident at the Mazury Club. The city in the film is nothing but a backdrop for carefree amusement and male protagonists ‘looking for their inner selves’. A lot has changed since then. Warsaw looks similar, but the atmosphere, inhabitants and socio-political reality are different. The women’s protests, refugee crisis, LGBTQ+ community bashing, climate disaster and, finally, the pandemic and Russian invasion of Ukraine have made it difficult to loose oneself in carefree frolics. Parties started having different purposes: from offering safe spaces, niches for non-heteronormative individuals, to fundraising, to manifesting political ideas, resistance and radical artistic expression.

I have spent the recent years in Warsaw on the dance floor, at parties organised by various artistic and music collectives, such as Turnusik, Wixapol, Galeria Śmierć Frajerom, Sonda, Bal u Bożeny. These sites of social gatherings, ferment and conversations have become crucial in bringing the young artistic community together. They are governed by the principles of equality and non-violence. These are places of identity formation as well as individual and collective expression. Artists who organisesuch cyclical parties treat them as total works of art – performative events in which every detail matters: venue, outfits, decorations, music, invited artists and performers. Each new initiative generates its own visual setting, a set of symbols and aesthetic approaches. Parties provide a platform for art performances, rap live acts, drag queen shows and poetry slams. Artists are invited to create set design and visual setting, and participants arrive in outfits matching the vibe. Many of the aesthetic formats employed by the collectives can be called nostalgic, or ‘hauntological’, to use Olga Drenda’s term.

The summer of 2018 was unforgettable, when we danced in front of the Embassy of Georgia in Warsaw, unaware that we would later be dancing out of anger at women’s protests, blocking the streets during the Extinction Rebellion demonstrations, or in order to forget at least for a moment about images of the Bucha massacre. That summer was animated by the queer-feminist collective Kem, working at the intersection of choreography, performance, sound and social practices, comprising Alex Baczyński-Jenkins, Kasia Właszczyk, Ola Knychalska and Krzysztof Bagiński. They were invited for a residency at the CCA Ujazdowski Castle to develop a year-long performative programme. In one of the castle towers, they opened Dragana Bar, entered via metal stairs leading through a window. Every two weeks, the venue hosted parties with electronic music and performances. The artists invited young, unknown DJs as well as performers, among whom I can best remember shows by Filipka and the drag queen Kim Lee, a star who died of Covid-19 one and a half years later. The projects were performative, community-based, and mainly involved building new relations on the basis of shared values.Later, due to the pandemic and a change of the institution’s directorship, the collective had to leave the CCA. However, it did not stop operating in the form of pop-up parties (at the Tango Milonga dance club, among other venues), performances (unforgettable Untitled Dances and Baczyński-Jenkins’ performative exhibition at the Foksal Gallery Foundation), and the Kem School by the Krytyka Polityczna Club in Warsaw. Dragana Bar does not belong to any specific place, it is created by dancing bodies, their desires and ideals.

5 Olga Drenda, Duchologia polska. Rzeczy i ludzie w czasach transformacji, Znak, Kraków 2016.

During the pandemic summer of 2020, when most festivals were cancelled, the visual artist Karolina Mełnicka rented a somewhat derelict communist holiday resort, to which she invited artist friends for a several-day party titled Mazury Club. That music and performative event, but also a purely social gathering that involved spending leisure time together, inaugurated a whole series of parties. The next one took place a year later at the old Kora swimming pool in Warsaw. In 2021, Mełnicka also organised a New Year’s Eve celebration ata former cafeteria in Kopernika St. in Warsaw. Aside from music, her parties are characterised by a specific visuality, referring to the Y2K fashion trend from the first decade of this century and ‘fairycore’ Instagram aesthetics. On these occasions, I became familiar with the rap band Xenon and JulekPloski’s music. There was also a performance by Danilfrom the Kiki House of Sarmata. Bohdan Mucha’s video-postcards from bombarded Ukraine were shown. The artist-curator always very carefully chooses the venues for her events and organises site-specific parties that refer to the history and atmosphere of a given location. This represents the tendency, characteristic of club culture, of appropriating strange new spaces in the city and on it outskirts, remaining on the margins, in secret locations. Mełnicka herself enters the role of a curator, inviting artists (Janek Porczyński and Dominika Olszowy, among other figures) to develop the visual setting and set design of the parties.

Michał Grzegorzek, a curator who co-creates this club-performative-artistic movement interpreted artists’ activities around bars and club culture through the prism of Nicolas Bourriaud’s relational aesthetics. The club is an artistic medium that enables meetings, staging provocative, critical situations focussed on interpersonal relations, rather than on autonomous bodies.I would alsoconsider the organisation of parties as a post-artistic activity, in which art completely merges with life and becomes a tool for changing the socio-political reality. Artists make use of their visual, organisational and performative skills to create something that goes well beyond the traditional understanding of the artwork. The most important thing is to have fun together, release stress, meet each other, and establish alternative safe spaces for minorities. The hazy smoking rooms and dance floors hot with bodiesemanate the scent of an upcoming revolution.

6 Michał Grzegorzek, Wokół barów (i w środku nich), w: Performans, red. Joanna Zielińska, CSW Zamek Ujazdowski, Warszawa 2020, s. 96–97.

Moral turn, post-irony and post-art

In the recent years, the young artistic community has seen a special kind of turn, which for the needs of this text I call a ‘moral turn’ in art. Numerous crises haveresulted inthe need to build new coalitions and rethink former ways of collaborating. During this period, we have experienced debates on values and morality. A certain unwritten code of ethical conduct in the field of art emerged. Located at its heart are questions concerning working conditions, ecological and feminist issues, inclusion of various minorities.This code contains tacit rules about whom to collaborate with and whom to avoid (because they violated certain standards, imposed censorship, lied, etc.), which is a manifestation of the debated and controversial phenomenon of cancel culture.

Faced witha higher-order need and sudden crises that shake us out of standard ways of thinking for weeks, artists are the first people to engage in activistic and prosocial actions. A pressing necessity has also emerged to look for new values and return to emotions. Confronted with the ‘the pain of others’,the Postmodernist ironic, critical and condescending perspective has been completely discredited. Young artists opt for emotional and honest attitudes, focussed on the search for values: truth, love, solidarity, friendship.

An example of engagement and taking things seriously are protests: from those concerning the climate, to anti-war manifestations, to feminist demonstrations, which derived their power from the visual message formulated by artists.Performances such as the march with flags at the antifascist street party For Your and Our Freedom in 2018 and Jana Shostak’s Screaming for Belarus have already gained an iconic status.Of note was also the participation of artist in women’s protests and developing their visuality. A major role was played then by young documentary photographers gathered around The Archive of Public Protests, who published several thematic issues of the Gazeta Strajkowa newspaper, and whose photographs circulated on the Internet, encouraging people to take to the streets. In the recent years, artists have engaged in numerous aid activities: preparing sandwiches for refugees from Ukraine, offering helpon the Polish-Belarusian border, organising charity auctions, working at refugee hostels, setting up libraries with LGBTQ+ books. It is difficult to distinguish a few specific figures as representatives of the post-artistic tendency. After all, blurring the category of authorship and the artwork is one of the principles of this movement. However, we can easily name the initiators and theorists of such activities. One of them is certainly Sebastian Cichocki, a curator (alongside Marianna Dobkowska) of the Postartistic Congress in Sokołowsko in 2021, Waldemar Tatarczuk with the radical interventionist programme of the Labirynt Gallery in Lublin, the collectives Office for Postartistic Services, Consortium for Postartistic Practices, and the recently established ‘Sunflower’ Solidarity Community Centre by the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw.

7 Susan Sontag, Widok cudzego cierpienia, Karakter, Warszawa 2010.

The concept of ‘post-art’ is an umbrella for many artistic approachesthat also enjoypopularity elsewhere in the world. In Poland, it has a clear theoretical foundation, described half a century ago by Jerzy Ludwiński. This theorist and companion of neo-avant-garde artists remarked: ‘Perhaps, even today, we do not deal with art. We might have overlooked the moment when it transformed itself into something else, something which we cannot yet name. It is certain, however, that what we deal with offers greater possibilities.’ We are currently witnessing a debate about the potential of art, its agency, and its use as a tool in the struggle for ideas. It can be ironically stated that the instrumentalisation of art is good as long as it is done by artists on our side of the barricade. Such activities are a double-edged sword, and they surely deserve broader reflection among young artists. They believe, however, that it is unethical to deal with ‘pure art’ when real action is necessary in the face of war and migration.

As opposed to the above described, mostly ephemeral and immaterial phenomena, we can also notice in young Polish art a renewed interest in traditional techniques and the materiality of art. It can only seemingly be associated with the dictates of the market and collectors, who want to buy objects. The longing for the material object, for exhibitions in a real space, has mainly been inspired by the pandemic, social distancing and the power of the Internet.Many artists use traditional sculptural and artisanal techniques in new ways, creating ceramics, objects made of fabric, metal, wood. However, their aesthetics is ‘glitched’, transformed by online forms and marked by contemporary reflection. Many such objects look like materialised online entities from games or memes. Artists make use of waste and trash aesthetics for the sake of drawing attention to ecological issues and evoking the atmosphere of a postapocalyptic world. Their paintings also reveal a certain nostalgia and return to aesthetics from the past. Representational painting reigns supreme, not far-removed from Surrealist, Symbolist and Expressionist tendencies.

8 Jerzy Ludwiński, Sztuka w epoce postartystycznej i inne teksty, Akademia Sztuk Pięknych w Poznaniu, BWA Wrocław, Poznań i Wrocław, 2009, s. 66.

The Discomfort of Evening is the first (and hopefully not the last) such vast survey of the young generation at the Zachęta, which seeks to map a broad array of phenomena. Every cloud has a silver lining – in the recent years, we have experienced anxiety, fear, a sense of being treated unfairly and having something taken away from us: institutions, rights, representation, agency, spaces, funding, travels. Our youth is riddled with crises. I feel that these difficulties and unexpected circumstances compel artists to consolidate themselves, invent new forms of action, manifest creativity, take responsibility for each other. They set up their own grassroots venues, search for niches on the Internet and in clubs, and seek to redefine the moral role of their work. Despite the sense that the atmosphere in the world is growing denser every year, I place trust in the community of young artists. There are certain values, ideas, experiences, hidden places: real and imagined, that nobody can ever take away from our generation.