No. 34

“Patronesses, visionaries, activists” – Bożena Kowalska

Aleksandra Zientecka

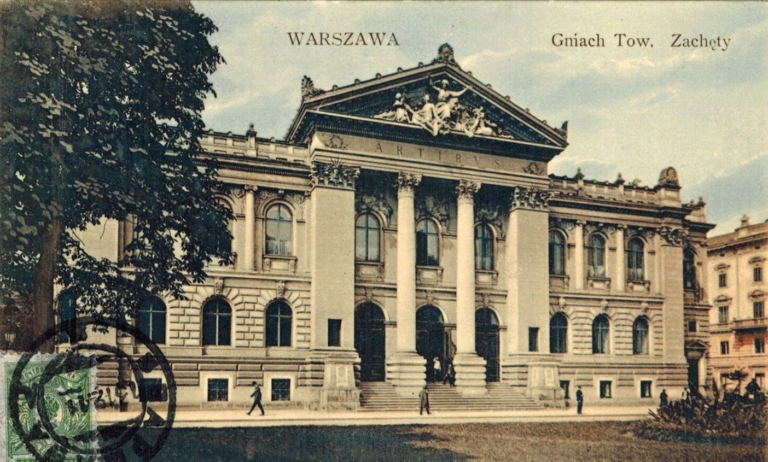

Bożena Kowalska is regarded as an art historian for whom geometric abstraction remains the most important trend originating from the tradition of avant-garde art. All her many years’ artistic initiatives and undertakings have been focused on this, and she has presented artists using the language of geometry. This has also been reflected in numerous articles, essays, and critical texts which Kowalska has regularly published since 1956. She is well known for her critical and curatorial activity thanks to her books and monographs, the exhibitions she has organised, the management of 72 Gallery in Chełm and, finally, the organisation of international open-air painting workshops. However, not enough attention has been paid yet to her educational activities carried out on behalf of Zachęta.

Bożena Kowalska summed up her work at the Department of Education1 in the book Z dziejów pracy oświatowej CBWA (History of the Educational Work of the CBWA), describing her professional experience from 1952 to 1984, first as an employee, and later as the head of the team.2 She recalls the beginnings of the Central Bureau of Art Exhibitions (CBWA, established in 1949), when the activities of the institution were mainly focused on arranging exhibitions, first in Warsaw, and then also in other provincial cities, thanks to a network of branches being created.3 As Kowalska writes, forms of educational activity at that time were limited to announcing exhibitions in the press and advertising them on static pictures displayed in cinemas before the start of screenings, as well as guided tours of exhibitions.4 It was not until the second half of the 1950s that the CBWA began to develop its programme of propagating and popularising art. On the one hand, this was due to new phenomena in contemporary art that were increasingly difficult to understand and required visitors’ appropriate preparation; on the other hand, de-Stalinization and the revival of artistic life, which relaxed the rules of official cultural policy, making it ever more and more crucial to ask questions about the role of art in society. Kowalska, the long-time head of the Department of Education, was one of the key people in this process, shaping new forms of educational activity and ways of teaching about art in the second half of the 20th century. It was she who created and implemented many innovative solutions and educational methods in the field of contemporary art, which were successfully developed in subsequent decades.

Schoolchildren were an essential target group of the Educational Department’s new programme. In addition to basic forms of activity, such as the guided tours of exhibitions by the Department staff, students and graduates of art history, such events as discussion meetings with artists, series of lectures and readings, screenings of films about art, and numerous competitions, started to be hosted. One of the most popular contests was the Perseverance Competition, established at the turn the of the 1950s and the 1960s jointly with the Warsaw School District Board of Education. It rewarded classes and pupils who systematically visited Zachęta and saw the largest number of exhibitions during the school year. In 1967-1971, the name of the event was changed to the Interschool Exhibition Visiting Competition. There were also declamatory contests, the competition How do you like it? for the most interesting exhibition review, and one for the best guided tour of an exhibition. These initiatives helped to increase attendances at Zachęta and establish relationships and contacts with teachers, which was to bear fruit already in the nearest future. They also inspired the creation of didactic exhibitions of reproductions. Such monographic and problem-based exhibitions (e.g., Colour in Painting, How Artists See the World, What is Graphics, Sources of Modern Art, Portrait/ Landscape/ Still Life in European Painting, Polish Poster), consisting of ready-made sets, travelled from school to school and were presented in corridors, classrooms and common rooms. Large-format reproductions were executed based on photographs taken from art albums and sent to a bookbinder, who glued them onto canvases and framed them. This allowed the most interesting works of art to be shown in the limited school conditions, according to Kowalska’s principle: “Reproductions, technically good after all, of objects worthy of popularisation are better than artistically poor originals”.5

The didactic exhibitions, accompanied by an appropriate commentary and introductory texts on selected issues, were presented as part of the show, along with lectures delivered by the employees of the Department of Education, became a kind of art history lessons. The initiative gained more and more popularity in schools over the years, which resulted in the systematically increasing number of developed sets. At the action’s peak in the mid-1970s, more than 500 presentations a year were staged, and 50 ready-made sets of reproductions were used. Such exhibitions, combined with lectures, also began to be shown in youth clubs, hospitals, sanatoriums, and even in military establishments and prisons.

Problem-based exhibitions at workplaces were of similar character, with the difference that those inaugurated in 1969, under the telling title of Art for Everyone, showed original works, while meetings with artists accompanied lectures and readings. Large production plants6 joined the CBWA and held monthly exhibitions of paintings and engravings, while organisers tried to ensure that works on display at each exhibition significantly differed in terms of their means of expression7. The painting cycle showed, among others, the pictures of Tadeusz Dominik, Ryszard Winiarski, Alfred Lenica, Marek Sapetto or Maria Anto.8 Another series focused exclusively on graphics, which were immensely popular in the 1960s and 1970s, presenting the works of Halina Chrostowska, Maria Hiszpańska-Neumann, Teresa Jakubowska, Mieczysław Majewski, Józef Pakulski and Ewa Śliwińska, i.e. graphic artists who, at that time, were a highly representative group of artists in this field. With time, however, the cooperation began to fade, and some companies took the initiative, trying to exhibit the output of amateur artists selected from among their employees active in the company art clubs. Some workplaces lacked committed people who could properly develop the programme and cooperation with the CBWA. Exhibitions were held ever less regularly, failing to develop the habit of visiting them among the workers. Besides, problems with adequately protecting works from possible damage cropped up. Despite these limitations, the programme lasted a full decade, and its organisers managed to maintain a high level of exhibitions, simultaneously meeting the political and ideological expectations of the authorities at that time.

The most important element of educational activity, however, was the Interschool Circle of Art Enthusiasts, established in 1962 and addressed to young people. Its initiator was Halina Osterloff, who was employed by Zachęta in the early 1960s and was one of Bożena Kowalska’s closest co-workers till April 1977. Kowalska remembers Osterloff as a friend exceptionally involved and devoted to what she was doing.9 The main programme objectives of the Interschool Circle of Art Enthusiasts were to teach young people how to think independently and interpret art, how to express their own opinions, and how to respect artworks and artists. As time went by, the Interschool Circle of Art Enthusiasts gained in popularity, and by the end of the 1960s and beginning of the 1970s, more than 500 participants joined it every year.10 It organised group visits to exhibitions, film screenings and trips to galleries and museums,11 as well as series of lectures on various topics and artistic issues. Lectures were given by well-known artists, critics, and art historians such as: Jerzy Jarnuszkiewicz, Roman Owidzki, Aleksander Kobzdej, Armand Vetulani, Stefan Kozakiewicz, Andrzej Osęka, Aleksander Wojciechowski, Wiesława Wierzchowska, and finally Kowalska herself.12 The most active members of the circle could participate in discussion meetings with artists during exhibitions, and above all, pay monthly visits to their studios. According to Kowalska, this form of direct contact with a chosen artist and his or her works enjoyed the greatest popularity among young people.13 The first such event was held in the studio of Alfons Karny, which was followed by, among others, Barbara Zbrożyna, Tadeusz Kulisiewicz, Józek Mroszczak, Janusz Kaczmarski, Jan Dobkowski, Jerzy “Jurry” Zieliński, Maria Anto, Edward Piwowarski, Zbigniew Lengren and Kowalska’s friend – Halina Chrostowska.14

In the years 1969-1976, the Circle offered another form of activity, i.e., Summer Holidays with a Sketchbook, two-week camps following the trail of the most interesting sights in selected provinces. The trips were led by Joanna Krzymuska, who worked for the Department of Education at that time, and Włodzimierz Bronicki (nicknamed “Sheriff”), an educator and Polish language teacher from a school near Nadarzyn. The camps combined the form of sightseeing tours with lectures given by participants, and open-air drawing classes, which gave the camps their official name. As Halina Osterloff recalls, the participants of the camps were also active after they came back home: organising meetings about art in their schools, giving short presentations, and even trying to create school Circles of Art Enthusiasts under the auspices of the CBWA.15

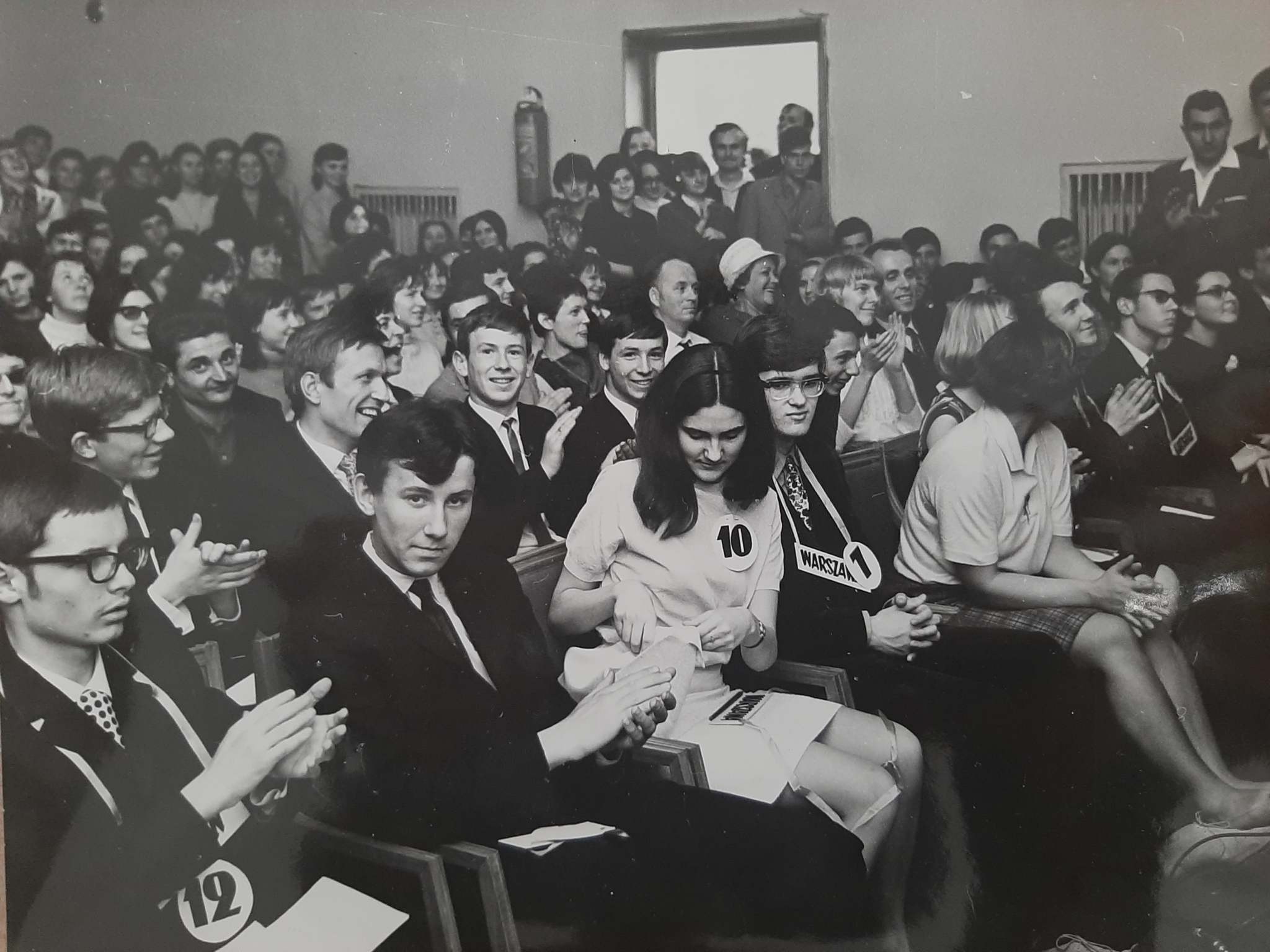

The activity of the Interschool Circle of Art Enthusiasts was followed by the National Art Knowledge Tournament (organised from 1963), which became a nationwide event with time thanks to constant cooperation with BWA (Bureau of Artistic Exhibitions) branches. Initially, the tournament was a local event, held only at the seat of Zachęta until 1968, and in subsequent years in Kraków, Lublin, Poznań, Sopot and Wrocław.

From 1974, the event was hosted permanently in Bydgoszcz, where “[…] it has found excellent organisers, the support of the authorities and a favourable atmosphere of interest and approval of the whole city. During the tournament, the museum, the philharmonic hall, and the best hotels are made available for its purposes, and, thanks to the event’s wide promotion, participants in the finals meet with signs of sympathy at every turn.”16

However, it was the staff of the Zachęta Educational Department who had responsibility for the substantive aspect of the competition, the development of questions, tests and tasks.

Tournament participants were mainly those who had taken part in the series of lectures corresponding to the theme of the competition in a given year. A standardised lecture programme allowed elimination rounds to be organised in all BWA centres a few days before the finals, thus selecting the two best candidates to represent a given BWA or a province in the finals of the annual tournament. The winners were awarded works of art and trips to other Warsaw Pact countries. They also earned extra points in their entrance examinations for Art History. In the mid-1970s, partly as a result of the annual tournaments, which gave an impulse and prepared the ground for further activities, the Ministry of Culture and Art announced the organisation of the Artistic School Olympiad, coordinated by the National Museum in Warsaw. The tournament formula was slightly changed so as not to lose the participants’ interest, and not only school pupils, but also adults, were invited to participate, with the reservation that they could not be professionally connected with art. The level of the contests was extremely high, requiring from the participants not only factual knowledge, but also the ability to independently interpret works and to look at art from an individual point of view. It was also emphasised that the competition provided opportunities to young people from smaller towns and cultural centres, who often became winners.

It was not only the National Art Knowledge Tournament that developed thanks to continuous cooperation with the local branches of BWA. The most important activities and initiatives of the CBWA were successfully transferred to Art Exhibition Offices throughout the country. There were more than 20 local Circles of Art Enthusiasts created on the Warsaw model. Moreover, in cooperation with local galleries, the Summer action, embracing meetings with artists, exhibitions, and visits to BWA seats, was run for young people on summer camps.

Summing up the Interschool Circle of Art Enthusiasts, it is worth emphasising that it offered an unprecedented, for those times, possibility of having conscious contact with art, awakening passions, deepening interests, and actively participating in culture. Its activities, throughout all the years of Circle’s existence, and especially the early decades, closely reflected the main assumptions of the Department of Education: the desire to link the educational process with artistic education of the youth and exert a consistent, cyclical and long-term impact on the target group.

Years later, the members of the Interschool Circle of Art Enthusiasts recall how important it was for them to be part of this leading educational initiative: “We were treated seriously at Zachęta, almost like adults, enjoying a lot of freedom, with everyone doing their best and feeling jointly responsible for the atmosphere.”17 To this day, they have retained many vivid memories of that time, often admitting how much participation in the meetings and trips organised by the Circle shaped them and influenced their later decisions and life choices.

Another form of Educational Department’s disseminating and popularising art among the youth was a two-year Teacher Training Programme. Established after the compulsory subject of art education had been introduced into the school curriculum, the programme offered teachers the opportunity to improve their professional qualifications.18 Distinguished speakers, art critics, academics from universities or the Institute of Art of the Polish Academy of Sciences, who specialised in art of particular epochs and artistic styles, were invited to give classes and lectures. Many of them were friends with Kowalska, and their relationships often dated back to their joint studies in art history.

Participants received additional study materials, i.e., compendia of knowledge on Polish and universal art, prepared as scripts and synthesising the issues discussed during lectures. The compendia served as a ready-made teaching aid for conducting classes at school. At the beginning of the 1980s, on the initiative of the CBWA and Bożena Kowalska, who established contact with the School and Pedagogical Publications (Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne), the completed and re-edited scripts were used to create two books edited by Kowalska: Dzieje sztuki polskiej (History of Polish Art) and Dzieje sztuki powszechnej (History of Universal Art,) being, as it were, ready-made textbooks on art.19 In addition, the Department of Education prepared a selection of 350 slides, including iconic examples of works of architecture, painting, sculpture and applied arts from prehistoric times to the present, and a similar collection of over 300 slides featuring Polish art: they served as illustrations for the texts in the compendiums. The sets, approved by the Ministry of Education, were distributed not only to teachers taking part in courses at Zachęta, but also to all BWA institutions and schools throughout the country that bought sets of scripts and slides. In total, around 5,000 sets were disposed of, which really contributed to magnifying the effects of the Teacher Training Programme all over Poland.

The training programme stimulated a lot of interest from teachers, with as many as 200-350 participants from Warsaw and the surrounding area attending it every year. Besides, in the autumn of 1970, the first course aiming at educators from outside Warsaw was launched, which attracted a record number of over 460 participants. By the end of the 1960s, the CBWA also helped to organise similar classes in Zielona Góra, Opole, Poznań and Wrocław. The high attendance, testifying to the participants’ great interest, proved the need for such initiatives, which were an excellent form of teaching and popularising art, also available to communities outside Warsaw.

Upon the end of the first edition of the study in 1968, Kowalska writes in her diary: “I conducted the drawing of annual passes at ‘Zachęta’ this week, and the one-year Art Knowledge Course for teachers finished on Friday. 28 lectures, 28 books printed on photocopiers, 28 evenings spent with this group of about 150 people. […] I was showered with flowers, so many nice things were said, so much gratitude! My voice trembled with emotion. The atmosphere was solemn and cordial.”20

The educational programme was also implemented with the intention of increasing attendance at exhibitions held at Zachęta. The sale of annual passes was a traditional form of building a relationship with the public, dating back to pre-war times, and entitling visitors to unlimited entry to exhibitions organised by the CBWA.21 Regular visitors, who bought such a pass, took part in drawings of works of art, organised twice a year by the Educational Department.

The prizes were oil paintings and prints by well-known and highly regarded artists, and the results and names of winners were regularly announced in the daily press: “No one needs to be convinced of the importance of annual passes to Zachęta in the whole set of educational activities aimed at making exhibitions accessible and attractive. However, there is no harm in mentioning it when the results of the next draw are being announced. The point is also that those who have spared no effort in continuing this campaign for so many years have no doubts that their efforts are needed and appreciated by other people.”22

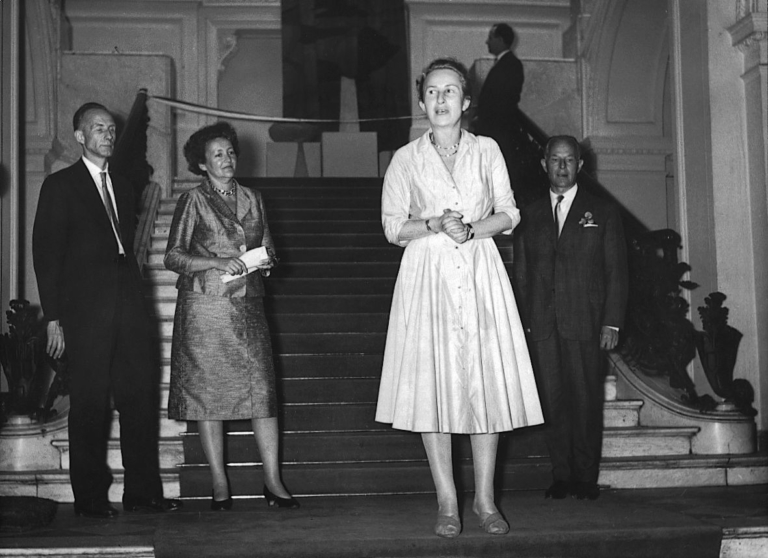

The subsequent draws were ceremonial evenings with performances by famous and popular actors and singers. On this occasion, Zachęta hosted Kalina Jędrusik, Irena Santor, Wojciech Młynarski, Mieczysław Fogg, Piotr Szczepanik, Wiesław Michnikowski, STU Theatre, “Pod Egidą” cabaret with Barbara Krafftówna and Jonasz Kofta, and many others.

These stars attracted large audiences: “These were huge events, with wild crowds flocking to them,” recalls Barbara Dąbrowska, later head of the Department of Education.23

Their organisation contributed to increased sales of passes to Zachęta.24 The prize draw is another example confirming a deep-rooted principle of educational work, in line with which Zachęta’s employees focused on long-term, cyclical, and systematic activities aimed at visitors.

Bożena Kowalska, as the head of the Educational Department of the CBWA, created a style of art education and introduced many innovative proposals addressed to new audiences. The fundamental rule of the department’s work of that time was, first and foremost, to maintain a a high scientific and organisational level of lectures and meetings, using the best examples of contemporary art. The focus was also on real, although often difficult to grasp, concrete effects of the activities undertaken. All outreach activities, ideas, and initiatives which were developed over the years influenced the evaluation and perception of the educational initiatives of the then very modishly conceived and managed department, which, thanks to Kowalska, gained complete independence. It made a key contribution to the popularisation and dissemination of art, and its ways of building relationships with the public, developing visitors’ interests through participation and involvement in various actions, had an impact on the whole of Poland, remaining relevant in many areas to this day.

1 The final name was given to the department in 1962 as the institution attained a new status, which entailed the change of Zachęta’s structure and the establishment of the Instruction and Education Department; cf. Statutes of the Central Bureau of Artistic Exhibitions, annex no. 2 to the Ordinance of the Minister of Culture and Art no. 6 of 19.01.1962, folder no. 15, Zachęta’s internal archives.

2 In the first years of her work, Bożena Kowalska was chiefly responsible for the creation of the library and documentation, which, separated from the Educational Department after many years, became independent departments of Zachęta.

3 The basic statutory tasks of the CBWA included the coordination of the so-called field branches, which were set up from 1950 and initially remained fully dependent on the head office. Changes occurred in the early 1960s, when these branches were transformed into independent budgetary units subordinated to provincial authorities. They also adopted the name of Bureaus of Artistic Exhibitions (Biura Wystaw Artystycznych, BWA) and began to carry out their own substantive activities, apart from cooperating with the CBWA.

4 Bożena Kowalska, Z dziejów pracy oświatowej CBWA, typescript in the documentation department of Zachęta, p. 2.

5 Ibidem, p. 7.

6 Willingness to cooperate was expressed first by six, and later nine other plants, among others: Marceli Nowotko Mechanical Works (Zakłady Mechaniczne im. Marcelego Nowotki), “22 July” Confectionary Factory (Zakłady Przemysłu Cukierniczego “22 Lipca”), Polish Teletransmission Works (Państwowe Zakłady Teletransmisyjne), Marcin Kasprzak Radio Manufacturing Company (Zakłady Radiowe im. Marcina Kasprzaka), Warsaw Pump Factory (Warszawska Fabryka Pomp), the High Voltage Equipment Factory (Zakłady Aparatury Wysokiego Napięcia), and the Polfa Tarchomin Pharmaceutical Factor (Zakłady Farmaceutyczne „Polfa” Tarchomin).

7 In her diary, Kowalska recalls in a note dated 5 March 1969: “On behalf of the CBWA, I am trying my luck in a workers’ experiment with the environment of the ZMS (Union of Socialist Youth). Yesterday, I agreed on the rights and duties of the CBWA and industrial plants in four locations in Warsaw as part of this cooperation. I gained the approval of Basia Jonscher (lyrical expression), Grześ Moryciński (new figuration), Leszek Okołów (simplified forms connected with a work tool and a bit Léger’s vision – the boy is employed in an industrial plant), and finally Basia Szubińska (making forms unreal to the point of abstraction, texture, and feminine lyricism). I wanted some diversity”; cf. Bożena Kowalska, Fragmenty życia. Pamiętnik artystyczny 1967–1973, Radom 2010, p. 99.

8 Kowalska wrote in her diary of 14 January 1970, “Yesterday, Maria Anto and I were at the Teletransmission Works, where my department is organising her exhibition. There were crowds of people at the previous meeting with Anna Lisiewicz. That discussion was stormy, touching upon broader problems of art and its reception […] Yesterday’s discussion, on the other hand, was strictly limited to the exhibits placed in the room”; cf. Bożena Kowalska, Fragmenty życia, op. cit., p. 158.

9 Interview with Bożena Kowalska conducted by the author, Brwinów, 17.10.2021.

10 In the 1962/63 school year, when the Interschool Circle of Art Enthusiasts was initiated, about 120 pupils participated in the programme. This was less than a decade later: in 1970, more than 570 people were enrolled.

11 Cooperation with Janusz Bogucki’s Contemporary Gallery started; meetings were also organised at the Museum of Art in Łódź and the National Museum in Warsaw.

12 Anna Żakiewicz, a museologist connected with the National Museum in Warsaw for years, who was a member of the Interschool Circle of Art Enthusiasts from 1971 to 1976, confirms the high level of the lectures, adding: “I was even disappointed when I went to university afterwards. […] everything was on a lesser scale than in Zachęta. I was spoilt by Zachęta”; cf. Zofia Dubowska in conversation with Anna Żakiewicz, Warsaw, February 2021.

13 Bożena Kowalska, Z dziejów pracy oświatowej CBWA, op. cit., p. 8.

14 The meeting in Halina Chrostowska’s studio was covered in a press article and an episode of a newsreel produced by the CBWA; cf. (Hen), Grafiki, tygrysy i „Tinta”, “Sztandar Młodych” 1965, no. 16, and CBWA newsreel, no. 1, production: Bożena Kowalska, Zbigniew Jęczmieniowski, photography: Jerzy Binder, Zbigniew Jęczmieniowski, 1968, Zachęta documentation department.

15 Halina Osterloff, Notatki i refleksje z pracy w zespole oświatowym CBWA, typescript in Zachęta’s documentation department, p. 10.

16 Antoni Soduła, Zbliżenie do sztuki, “Głos Nauczycielski”, 9.09.1979, no. 36.

17 Zofia Dubowska in conversation with Anna Żakiewicz, op. cit.

18 The initiative was gradually developed over the years, with the participation and involvement of the Ministry of Education and the Institute of Teacher Education and Education Studies (IKNiBO).

19 Dzieje sztuki polskiej, ed. Bożena Kowalska, Warsaw 1984, 2nd ed. 1987; Dzieje sztuki powszechnej, ed. eadem, Warsaw 1986, 2nd ed. 1990.

20 Bożena Kowalska, Fragmenty życia, op. cit., p. 44.

21 Kowalska mentions that holders of annual passes were treated as potential future members of the Society for the Encouragement of Fine Arts; cf. Bożena Kowalska, Plan działalności oświatowej CBWA, 8.03.1982, Zachęta’s internal archives.

22 (wk), Nagrody dla bywalców „Zachęty”, “Życie Warszawy”, 30.07.1982, no. 167.

23 Zofia Dubowska in conversation with Barbara Dąbrowska, Warsaw, 19.02.2019.

24 More than 520 cards were purchased in 1968, 460 in 1969 and 900 in 1970.