No. 30

Living a Feminist Life

A conversation with Magdalena Komornicka, Agnieszka Różyńska and Liliana Zeic (Piskorska)

07.07.2021

Magdalena: I would like to ask you to try and go back to last year for a moment, and remember the Languages of Radical Sensitivity event, of which Living a Feminist Life is a continuation. Last year, I felt that as a representative of a socially responsible cultural institution, I had to respond to the worsening of discrimination and violence against marginalised groups. It seemed to me that as a society, we are not linguistically prepared for such a discussion. So with these intuitions, I called Liliana. What else can a curator do other than call an artist? And then Liliana called Agnieszka.

Liliana: We started our conversation with sensitive and inclusive language. The Polish language has been changing a lot recently; we use new words, or use words differently, calling attention to linguistic violence or exclusion. Language is very important in my work; I’d even say increasingly important. I’m interested storytelling, fable writing, the radically poetic and sometimes the radically unpoetic. I wonder how we can tell each other stories so that we can believe them, how we can talk about emotions. I really like the quotation from Matthew D’Ancona’s Post-Truth: ‘the truth is not enough’. This sentence says that the language of facts is not enough, that we need a new language to trust and understand each other. That’s why I’m most attracted to the search for this language, to looking at language as a product of culture. And that’s why I like to play with language and observe the changed that take place within it: in the public space, in the political arena, but also in everyday life. Even a few years ago, the use of feminatives was mocked; today, we are in a completely different place.

Agnieszka: A few years ago, when I started writing emails starting with ‘dear all’, it caused an outrage. What does that even mean? It’s so impersonal, and so on. Two years later, the same outraged people started writing and speaking like that themselves.

M: It’s proof that our daily practice has had a real result. The change was possible as a consequence of consistently using those forms. I stress the importance of practice because it was the subject of our reflections last year — we considered what language sensitivity was and how to practice it.

L: Agnieszka put it really well — she said the change was a side effect of being together.

A: We’re used to language being a system of symbols and meanings we use to describe reality. But language has a great deal of performativity in it, and it is not just a description, but a component of the reality we all create together. If we put a ‘filter’ of radical sensitivity over our communication, it’ll turn out that, among other things, we listen differently, more deeply, that we can hear things that are new, strange or incomprehensible to us. As you know, I play with inflectional endings, using both feminine and masculine forms when speaking about myself. It’s a little more complicated in Polish, since our language is inflected and gendered, but it’s like an English-speaking person using feminine/masculine/gender neutral pronouns. Yesterday, a long-time friend asked me — just like Magda did recently — whether it was a problem for me that she speaks about me and to me, using feminine forms. It always makes me happy to have people ask about this, to find out how I feel about it. That’s what we dealt with last year — how to take note of communities, identities, of the problems of those people who are marginalised. And today we meet to build a safer space for them and to develop our feminist practices.

M: We started with language, but we focused on the daily practice of language sensitivity, which leads to things like creating feminine forms of masculine nouns, which allows us to notice in language, and consequently in our surroundings, the absent or invisible things that are not represented. We want to call attention to these invisibilities and absences in this year’s programme of meetings, workshops, performances and actions in plac Małachowskiego.

L: For me, it’s part of my artistic practice.

A: In my professional activities, which consist of curatorial and educational work, as well as developing safer spaces for marginalised people, I apply the practice of radical sensitivity, which means expanding the formulas of participation we know. I seek to open up the spaces we close down because we feel safe and comfortable in them. I want to keep redefining places, communities and spaces where we could feel safe — this is the result of my feminist involvement, my awareness of functioning in Poland as a queer person with the life experience of a woman. My background and class perspective have led me to search for a language that will be understood to more than just people from my community.

M: I think we have to explain what radical sensitivity is. I remember the heated discussion in social media over the meaning of the world ‘radical’ in terms like ‘radical sensitivity’ and ‘radical empathy’. How can sensitivity be radical? How can empathy be radical?

L: I read a text recently that talked about how we find it easier to be empathetic towards people who are like us. That is why for me, putting the adjective ‘radical’ in front of words like sensitivity and empathy means sensitivity not only to one’s social group, not only to those with whom we can easily identify.

M: On the other hand, the adjective ‘radical’ is defined by the Dictionary of the Polish Language as ‘seeking fundamental social and political changes’. So for me, it means making sensitivity or empathy a political tool.

A: For me, radical sensitivity, radical affection, radical empathy turn us towards working from the bottom-up, to be uncompromising in creating tools to love, respect and accept each other. Not just tolerate, but accept!

L: This expression also contains the postulate to politicise things that are considered more feminine, less inscribed in the patriarchal structures and schemas, like, care, affection, sensitivity, sisterhood, etc.

Magda, why did you decide to continue the programme dedicated to sensitivity at Zachęta?

M: Last November, you conducted an online debate that was viewed by several hundred people, and later also workshops on practising radical sensitivity, which we had to repeat because of the number of people interested. This response from the public made me realise how much we need the eponymous sensitivity in this politically specific time, during the pandemic and the growing crises. I also believe that you have to talk about things like this all the time, just like the climate crisis, because we reach new people every time. It’s also an ecological activity to develop already existing potentials and to use the resources we had, so I wanted to continue what we started. Last year, we could only meet virtually; now we can invite the public to the square in front of Zachęta and be together physically, talk face to face. I also think that educational activities like this need to be regular — just like with feminatives, if we use them consistently, they’ll become part of the language and it’ll change. If we talk consistently about some things, that will also lead to change. I dream of our programme being widely available. The Zachęta public is very diverse — young, old, more conservative and more progressive. I would very much like to talk about practising sensitivity with all these people. That’s why this year, we decided to put together a four-day public programme that we called an open sisterhood-picnic seminar. We decided to create a space for being together in the square in front of Zachęta. We called the programme Living a Feminist Life. Liliana, why this title?

L: The title comes from Sara Ahmed’s book, Living a Feminist Life. We wanted our programme to be an opportunity to introduce people to Sara Ahmed, to what she writes about and how she does it. I really wanted us to follow this specific book because I believe that it is the best example of practising intersectional feminism — anti-racist and queer. Ahmed emphasises that whenever she uses the word feminism, she means intersectional feminism, which takes into account inequalities not only on the level of gender, but also, among others, on the level of skin colour, origin, social class, psychosexual identity or degree of ability. The term ‘intersectional exclusion’ is often used to describe this overlapping of exclusions.

A: This description comes from the experience of Black women living in the US, who remember the times of apartheid, and who personally experience the class divisions and racism that are still very present. This intersection of exclusions shows how very different we are. Just like Polish suffragettes didn’t think of the peasant women, or those who came from the countryside to the cities, or the women who worked in factories, American feminists didn’t think of people like their servants.

M: Why is the book Living a Feminist Life so important to you?

L: Ahmed manages something rare and valuable — the things she writes about theoretically, I understand corporeally as my own experience. She also has a great ability to put things into words in an incredibly poetic way, to look at words from every angle and wonder what will change if we look at it from a different side, in a different light, from a different perspective. I think this book could be a feminist ‘how to cope’ bible. It’s written in an accessible way and thus has a potential to read a wide circle of readers. I would be very happy if it was published in Polish. For all these reasons, we decided to make the book our ‘guide’ and ‘companion’ during this summer programme about language, words, reflection about the potential of storytelling, and examining language from a queer-feminist sensitivity perspective.

A: Moreover, the three of us lack a certain way of looking at things, since we were all raised in Central Europe in white bodies. Sara Ahmed teaches us how to go deeper with our cognitive mechanisms and sensitivity to enrich our wisdom instead of expanding our knowledge. Deeper, not broader.

M: Can you talk more about the programme, how we want to achieve all of this? What space are we planning to create? Beyond planning specific events, building an atmosphere and a place for conversation is very important to us.

A: We consider interdisciplinarity and mixing languages important — we want people to join the conversation performatively, with the language of art, activism, with poetry, and so on. In these combinations, in being together, we want to make possible a conversation where we can make mistakes, where we can have differences, but despite that, listen to each other to come to an understanding. For me, the lawn in front of Zachęta in a central spot in the capital city of our country is a symbolic place of getting used to the fact that changeability and diversity is our only constant.

M: I think we need to repeat that we can make mistakes and ask questions, since there is a belief in public opinion about a kind of terror of linguistic political correctness.

L: That’s why we decided not to hold traditional debates or discussions, but to create a space for everyday conversations. We don’t want to discuss via arguments, but listen to each other. That’s why we’re not going to invite ‘experts’ but instead, people who will share their experiences.

A: If doesn’t matter if someone considers themselves to be a feminist, we’re interested in how to live a feminist life. We’re interested in people who have the courage to go beyond the things learned in the patriarchy and who are open to bringing about change.

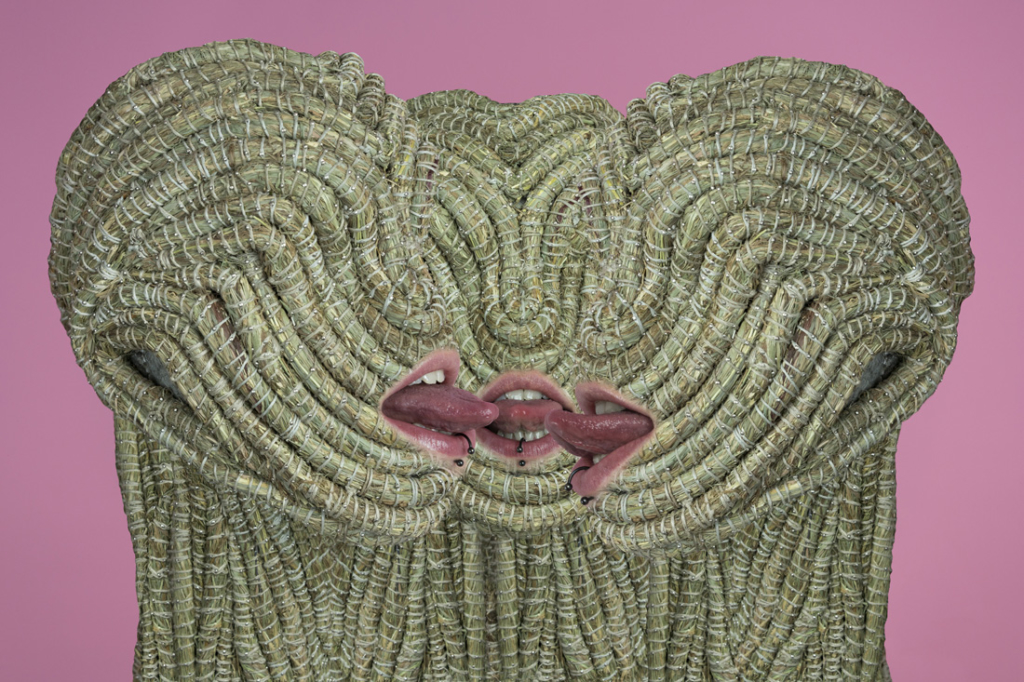

M: The programme opens on 15 July with Liliana’s performance A Pine with Six Hands. Can you tell us about this work and the idea of using the storytelling formula itself?

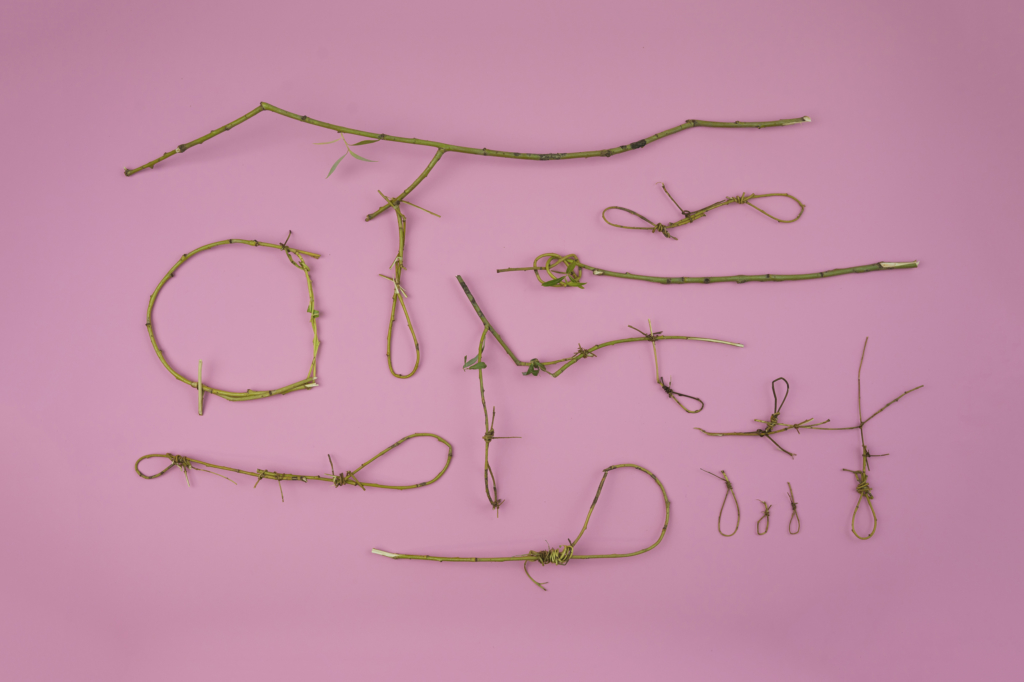

L: A Pine with Six Hands is fable I wrote, which will be presented as a bedtime story by queer drag queen Twoja Stara. It’s a way to reference a certain stereotype, a right-wing calque — the image of the drag queen reading to children. Through this fable, I recall the story of one of the first trans women mentioned in the literature of our region. I invoke her figure and wonder how we can talk about such historical people and build queer feminist archives in a way that is more than just recalling names and dates. We want to start the programme with a fable and invite the public to sit in the square, on comfortable loungers or on the grass, to immerse themselves into the fable reality. Reading and listening together, written and spoken text, coming from personal experience and testimony, will be the foundation of our programme.

A: The fable as a genre also contains the tradition of passing knowledge from generation to generation. A fable talks about universal values that can be described with different stories and transposed onto different situations each time. Starting with a fable, with the whole meaning system that allows us to look at reality metaphorically and deeply, is a symbolic start for me.

M: We interpret storytelling as a potential feminist-queer strategy of reclaiming visibility. I remember speaking with Liliana about Caroline Criado-Perez’s book Invisible Women. We think we know so much, that we have high sensitivity, that we deal with the same topics every day, and yet we are still constantly surprised by the lack of representation, exclusion, silence or invisibility.

L: Ann Snitow said that forgetting is the constant retelling of a story without including some themes or elements. Forgetting is the stubborn casting of certain specific motifs or themes, people and ideas outside the margins of history. It is a persistent denial that shows that it is politically motivated. Noticing is also a process. We learn to notice all the time — to notice anew, to notice more. The result is the broadening of our field of vision, paying attention to things hidden beyond the limits of the picture. An awareness that if something (an event, an idea, a person) is at the centre of our vision, that means that there is something else beyond it. Perez’s book is so saturated with examples of exclusion and omission that I could not read it continuously, I had to portion it out. Magda, you said that your partner didn’t know that all women are scared to walk alone after dark. For me, this very simple example really clearly shows how different the areas of our privileges are, and how hard it is to see this privilege.

Sara Ahmed put it very simply: ‘Privilege is an energy saving device’. It lets us save energy, not use it in certain areas of our lives and not notice that other people can also walk those paths at night, but that the path itself will be a completely different experience for them.