No. 32

He was amused by things that didn’t make everyone laugh

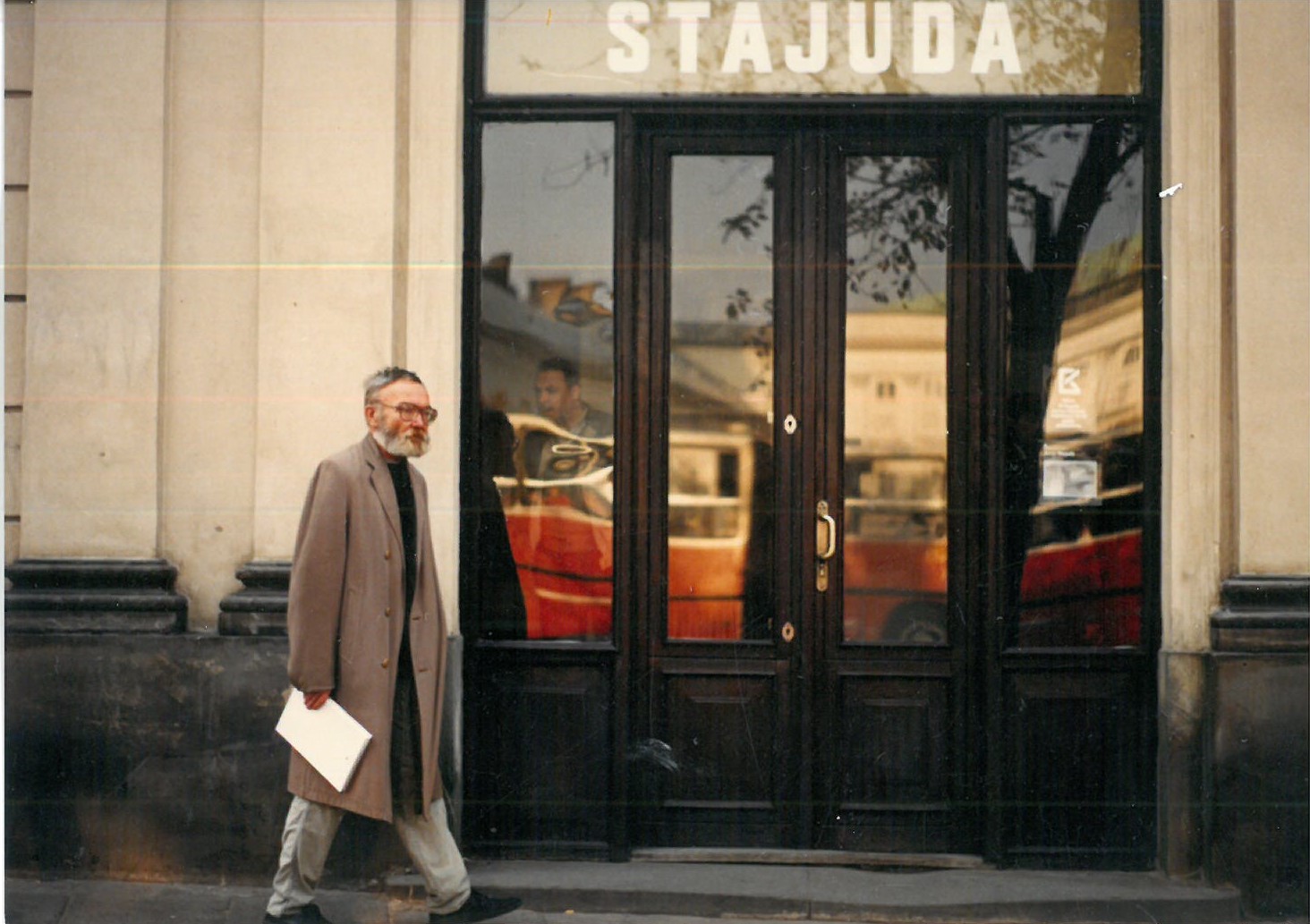

Karolina Zychowicz talks about Jerzy Stajda with Ola Semenowicz

22.09.2021

What year did you meet Stajuda?

It was at the beginning of martial law. But no, it was the summer before martial law was imposed. I was introduced to him by Elżbieta Szańkowska, who worked at the library of the Academy of Fine Arts1. She was a wonderful librarian and a great person. She thought I could help taking care of his children (Stajuda had two sons, one little, five-year-old [Jan], and the other thirteen or fourteen-year-old [Jeremi]). I didn’t find him interesting at all. He was sitting with Jan in the square at Mokotowska Street and they were both smeared with ice cream. They looked so happy, but they scared me. So I pushed the problem away from me. But Jerzy would pop in here and leave, for example, a rolled-up card or a match in the keyhole. He meant it to be a bit suggestive, but initially I didn’t quite get it. He had to explain it to me later. My sensibility wasn’t honed in that area, so I learned a lot from him. Eventually he started coming here, terribly unkempt. He had long hair but no beard.

So he was a hippie?

You could say so, but he wouldn’t join anything that could be associated with a community. As an architecture student, he was a member of the Polish Youth Union (ZMP)2, an organisation they all had to join at that time. Otherwise, they wouldn’t have left him alone. He wore a red tie (crocheted by his mother) which they forbid him to wear. He soon dropped out. All these students had gone through terrible things. But they were happy to attend painting classes. Jerzy could draw beautifully. In the Museum of the Academy of Fine Arts, there are a lot of his drawings – churches, houses – from the time when he was studying architecture3. He drew them for himself, his colleagues also asked him to draw for them, he had a knack for it. He probably traded drawings for vodka or cigarettes. Or for nothing.

You probably started hanging around Stajuda’s legendary flat of at Wiejska Street?

The first time I saw this flat in an old tenement house across the street from the Czytelnik publishing house office, all in craquelure, I was completely unprepared for something like that. There was a balcony, but no heating. There were tile stoves, but no one used them to heat, there were only electric heaters. Occasionally a piece of paper or some clothing that was drying there would catch fire. There were various incidents like that. The loo was like that too. The most interesting item was the floor, made of beautiful old wooden panels, very decorative, of black and light oak. It was all moving. When you walked on it, it felt like sailing somewhere. Unbelievable. Once, I managed to persuade Jerzy to sweep the floor and even wash it. He said: “Great, it’ll be like on a ship. We’ll take scrub brushes and we’ll scrub it like the deck of a ship.” I was able to bear it all because I could run away to my place in Mokotowska Street.

In the articles I gave you Marek Nowakowski and Tadeusz Nyczek write amazing things about this flat4. Fortunately, it was filmed by Piotr Morawski after Stajuda’s death5. In 1993, the Centre for Contemporary Art hosted a very successful exhibition: On a sunny I walked as if I had died6. It was prepared by Grzegorz Kowalski and Waldemar Baraniewski, with help from the exceptionally kind director Wojciech Krukowski. A lot of people got deeply engaged. Piotr was filming the flat when the furniture was being moved out – just as if they were carrying out the coffin. A round table, a sofa, and a harmonium – all of these were put on pallets covered with wood and metal mesh in the Centre for Contemporary Art. They looked like crates prepared for shipping to the United States. For a delayed trip. It was very beautiful.

But the relationship developed.

We would see each other more and more frequently. I was entering not only Stauda’s personal life (the boys), but also his circle of friends. Here I was delighted. Visiting Jerzy was very interesting and home exhibitions began, in which I had an intensive role. I made invitations for them.

At that time, I had been already working in the theatre for several years as a stage designer – in Cracow, Warsaw, Katowice, in many other places. Jerzy always told me: “Remember, Oleńka, you only work with the best. Never work with average directors because that will hurt you.” And I had the opportunity to work with Tadeusz Łomnicki, Janusz Nyczak, and Krystyna Meissner, who was my director at the theatre in Toruń for several good years7.

Stajuda was visited by interesting personalities.

Dozens of friends. Jerzy’s works were hanging on the walls, but we wouldn’t really talk about them. Julia Hartwig used to come with her husband, Artur Międzyrzecki, Jerzy Grzegorzewski, always elegant in a white trench coat, Leszek Terlecki (while visiting the Czytelnik office), and his wife Barbara were also guests at home exhibitions. Unc [Jerzy Stajuda] was sitting at the easel, they were talking, I served them tea, but also pricked up my ears carefully. Also came the quiet Rajmund Kalicki from ‘Twórczości’, the handsome Marek Nowakowski8. These were mostly writers. When we started attending the Warsaw Autumn Festival together, musicians began to drop by. Before that, Jerzy went to classical music concerts. He loved music very much and was a real connoisseur. Young musicians adored Stajuda. Paweł Szymański and Tadeusz Wielecki were his great friends9. After all, it was for Jerzy that Szymański wrote Quatre pièces pour Stajuda. The Silesian Quartet played it at an exhibition at the Centre for Contemporary Art. Witold Lutosławski was also there and his Grave10 was performed. Jerzy admired Lutosławski, listened to his music with the score in front of him. Lutosławski once saw it and was delighted. One day, Stajuda and Lutosławski stood in front of each other in the Philharmonic Hall. And suddenly they knelt down. Unfortunately, no one photographed the scene, only I witnessed this incredible moment. Lutosławski loved Jerzy’s painting. He received a large painting that was later displayed at the CCA (Jerzy gave it to Lutosławski himself during an exhibition at the Kordegarda in 1991). Many musicians bought paintings from Jerzy and came here to pick them up. He wasn’t very popular in Poland. He didn’t even try. Some people thought highly of his drawings, but his watercolors didn’t appeal to them. But, in 1988, at a big exhibition in Łódź, prepared by Ryszard Stanislawski, a lot of paintings and drawings were shown11. Stajuda himself was the author of the exhibition.12

What was the exhibition like?

It was huge. Drawings and paintings, including the gorgeous Birthday postcard for Samuel Beckett13. Jerzy’s uncle, a prelate in one of the churches in Łódź, was extremely shocked by this exhibition14. There were a lot of erotic drawings.

So he only had two big exhibitions in Poland?

He generated more interest in art galleries abroad. Musicians bought from him, but apparently no visual artists. Writers – Leszek Terlecki had two beautiful paintings at his place. Aleksander Wojciechowski had Jerzy’s works15. Together with Ryszard Stanislawski16, he participated in AICA activities. They went to Gdańsk to attend some exhibition or congress, had a great time, and Jerzy later told incredible stories. Stanislawski liked and valued Jerzy very much, and made a big exhibition for him at the Museum of Art, because he considered him a great artist17. Grzegorz Kowalski also thought highly of Jerzy, but I don’t know if it was for art or for the kind of man Jerzy was18. Original, real.

So he was appreciated by critics.

Only to a limited extent. Perhaps because Jerzy wasn’t much keen on organizing exhibitions.

Lots of his works are abroad.

Yes, if you wanted to do a big exhibition, you’d have to search abroad. In Belgium, France, and America. A lot of watercolours landed in London.

A person often gets separated from his or her art, and art manifests itself in personality.

Indeed!

Only that it is difficult to grasp later on.

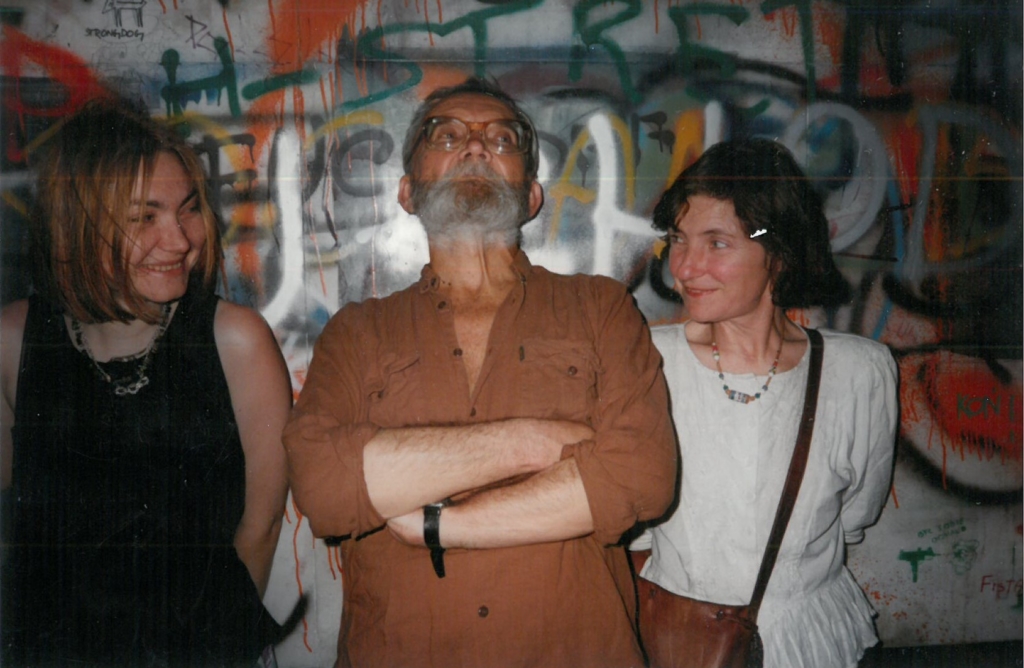

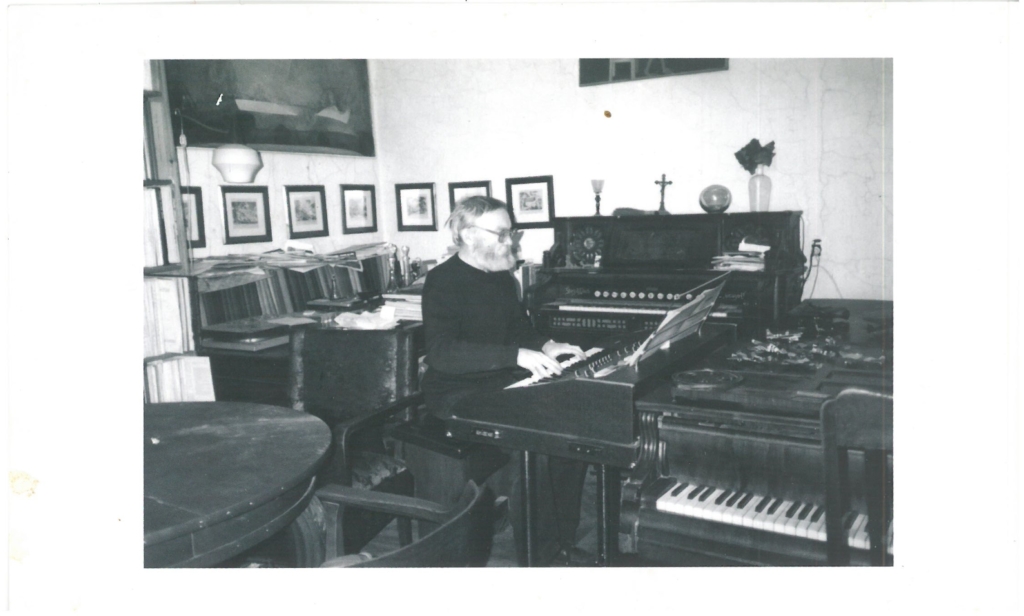

Grzesio Kowalski invited Jerzy to his studio as a professor of drawing. The students loved him because he invited them home. They would come with their drawings, which they discussed at the round table. Of course, they drank vodka and listened to music. Kasia Kozyra used to come, she fell in love with Jerzy19. In Kozyra’s thick catalogue, you can find a long article about her and Stajuda. I really have no clue why she wrote there that I was jealous. I wasn’t jealous of her at all, neither of Dorota Szwarcman, an outstanding musicologist with absolute pitch who idolized Stajuda20. Amazing person! She’s able to spot the wrong note of a single instrument in the orchestra. She has great knowledge. She and Jerzy would play the pianos late into the night, so that a neighbour banged on the ceiling with a broomstick to get some peace finally. And I would leave not because I was jealous. I simply wanted to go to bed because the next day I had to go to Łódź or Cracow. And here Kozyra says, and it will remain there until the end of the world, that I was jealous of Stajuda21.

Now we will publish your disclaimer.

Perfect!

How would you describe Stajuda’s personality?

He had a great personal charm, part of which was also that he was very modest, even shy. That’s why he felt more at ease when he took a shot. He was always ready to have some fun, have a nice laugh, do something offbeat. For example, we were riding a tram and I said: “Look, what at this beautiful girl in front of us.” He looked and said: “Yes, but she’s got curtain hanging in her eyes.” Curtain hanging, which meant that she was a housewife – that was the end of it, nothing to write home about. And in Paris, when we were sitting in cafés, he would say: “I’d talk to this one.” He spoke French reluctantly, he thought that he didn’t speak English well enough (his English was better than French). He was a perfectionist and didn’t take on things that he couldn’t do perfectly. Only when he drank, he was able to talk freely. He controlled himself about everything, but in painting he picked up speed. He enjoyed it, much needed it.

Everyone said he wrote fantastic texts. He worked in “Miesięcznik Literacki” monthly with Włodzimierz Sokorski, who was called Uncle Chill22. He was very fond of Jerzy, who collaborated with the monthly as a proofreader. You could say he was a grey eminence. I used to go with him to the printing house, where he picked up galley proofs. He would go home and crouch by the couch with a cigarette. Later he drank strong tea. And he was browsing through the text: he would open the page, glance it all over, and he spotted the errors. He noted them down on the margins. One glance was enough. He worked fast and everyone admired him for it. He had enormous historical and literary knowledge, he knew where a mistake was made. Lots of people would call him to ask when someone lived or what important thing was said by someone else. He would read all the time, he had books lined up in three rows in his flat.

He was from a generation of artists who could also be critics. This is rarely the case now.

When he was an art critic, he didn’t paint. When he started painting, he gave up criticism. When he received students at home, they were amazed at his stacks of books. There were also rows of vinyl records. He didn’t like CDs, didn’t want to use the technologoy. He was quite old-fashioned about it.

Today he’d be very much in vogue.

Only few artists would come to his home exhibitions. Jurek Kalina was one of them23. He drank like a fish, he was the last to leave in the morning. But he would put Jerzy to bed nicely, and then sit with me. Otherwise you’d mainly have the literary circle and musicians.

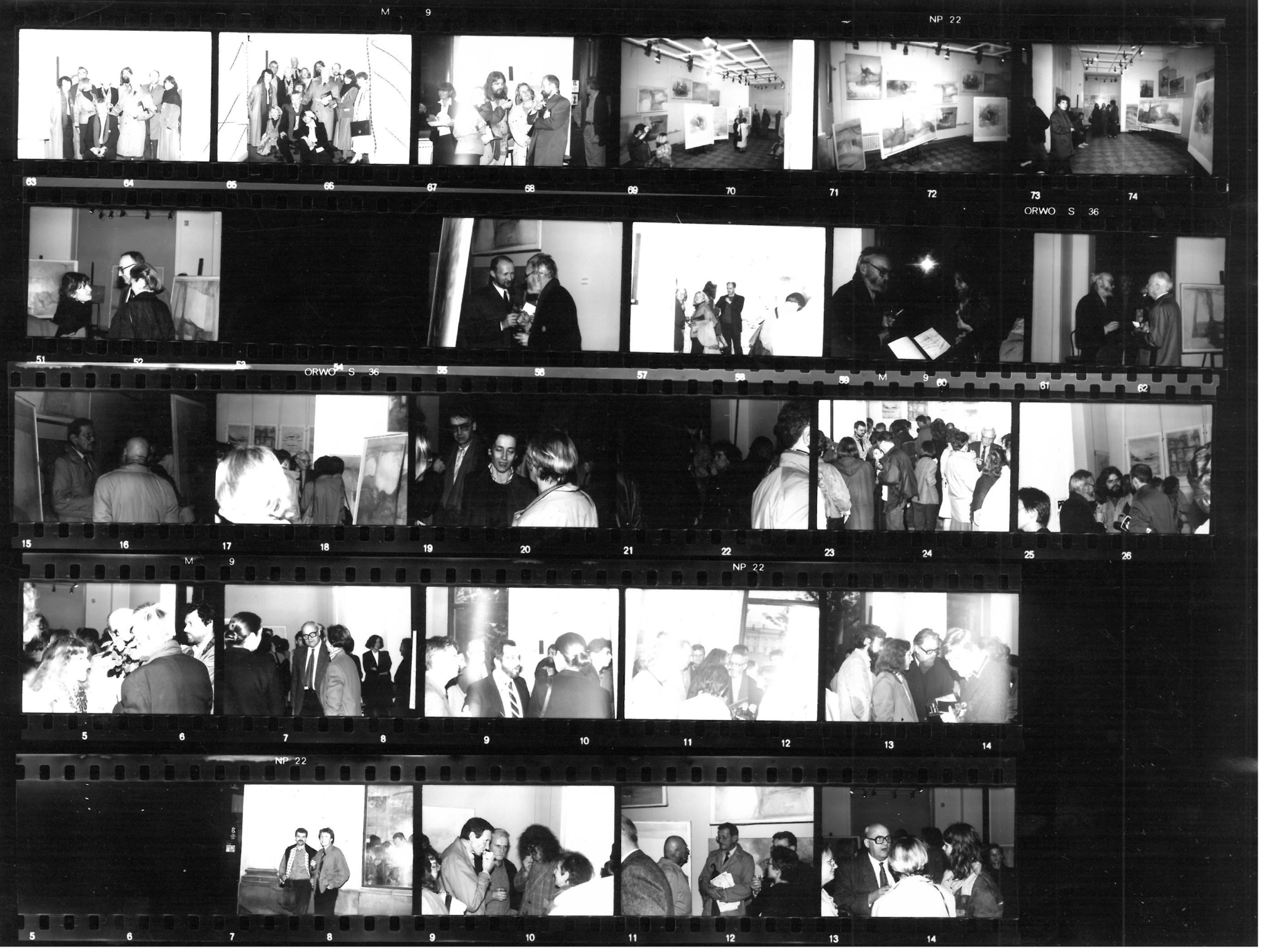

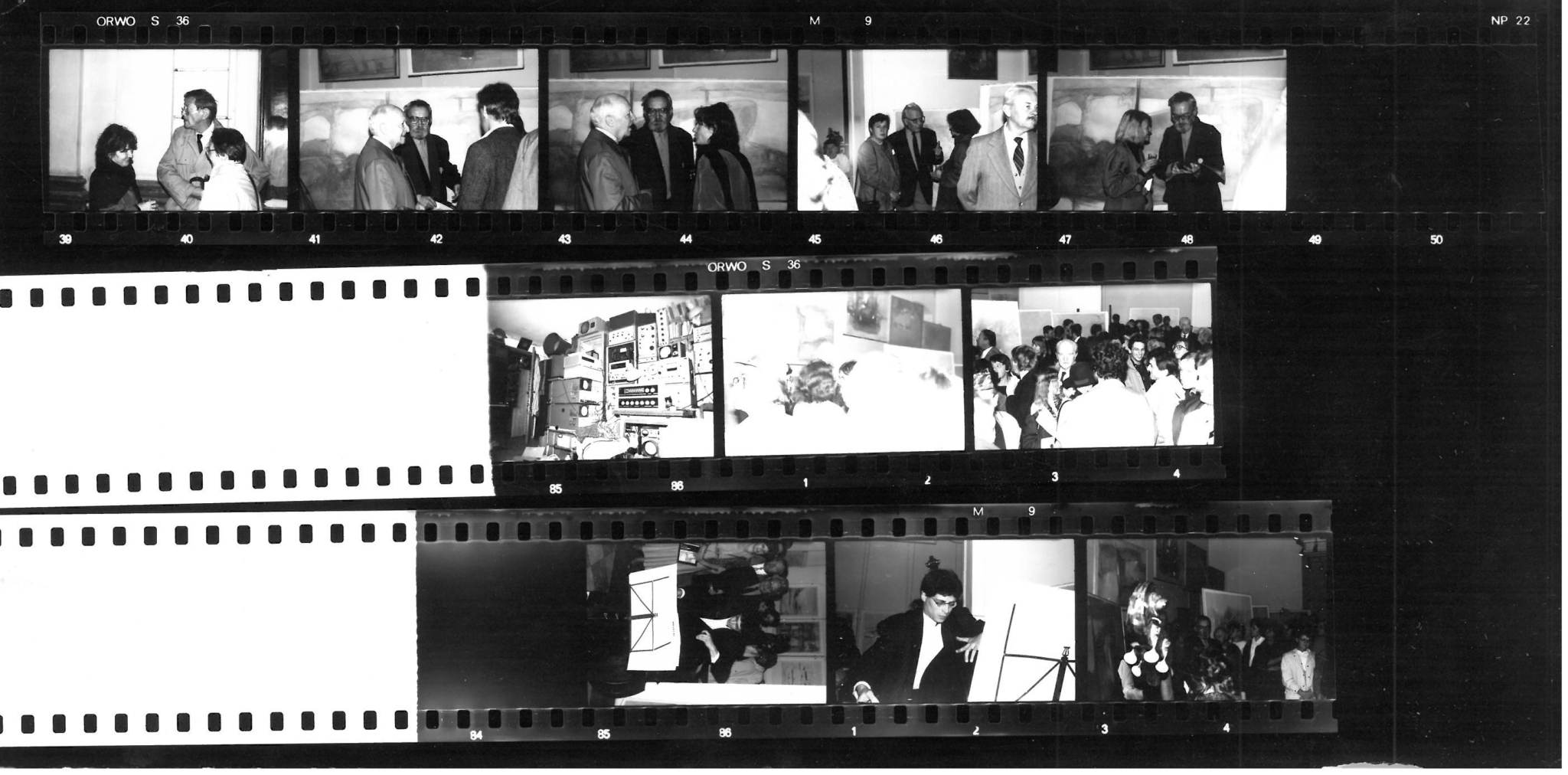

[Ola shows the photos]

These are home exhibitions. Let me find the albums. Can you recognize him? This is Maciek Gutowski, he also drank like a fish. This is Jola Zabarnik-Nowakowska, Marek Nowakowski’s wife. And here is Lutosławski’s wife, Danuta. And this is Edward Wende. That’s how it looked, it was so crowded. Look, what was going on here. Here is the beloved Andrzej Dłużniewski, and here Jan Stajuda [Jerzy’s son]. He was such a little boy then. Maria, Tadeusz Łomnicki’s wife. And here is the famous Józek Patkowski. Musicologist, he always opened the Warsaw Autumn. He spoke two languages: Polish and English. The man in the back is Anda Rottenberg’s husband. He was very nice24.

[Ola makes sandwiches]

And this is the wonderful Krzysio Kelm25. His wife, Beata, is talking to Jerzy, hugging him, and I wasn’t jealous at all either.

And this is Antoni Libera.

We were very good friends with Antoś. Maciek Szańkowski, Grzegorz Kowalski, and Elżbieta Szańkowska, who introduced me to Unc. Wojtek Freudenreich, a great graphic artist26. Jola Zabarnik-Nowakowska, an excellent lawyer, is standing with her back to us. And this is a lovely man, piano tuner Stanisław Mockałło (Jerzy had two grand pianos). This must be Mr. Dobrowolski, I think. This handsome guy is Marek Nowakowski and his wonderful wife Jola. Julia Hartwig, and next Ewa Wende – a beautiful woman. And this is my great friend Michał Kwieciński27. Paweł Szymański, who had beautiful, long hair. If you want, I can play Paweł’s music for you. Jacek Baszkowski, a painter, painted such small pictures28. He died tragically, he was Michał Kwieciński’s brother. Józef Patkowski, and this is Emilia, Andrzej Dłużniewski’s wife.

[the parrot says: “all quiet”, Ola pours more wine]

Stajuda had another great trait, an amazing sense of humour. A bit English. He was amused by things that wouldn’t make everyone laugh.

I can remember the story of how he shocked some girls on the train.

He was coming to see me at the première in Toruń, and he had with him a bag with Henry Miller’s Lexus with a provocative cover, and a big bottle of cognac.

He liked to drink with my tailors. When he had a drinking company, it was a very good company. And he sometimes had to wait a long time when I was busy running from workshop to workshop before the première. He was sitting and had nothing to do. So I said: “Go to the tailors.” When I was leaving, he was already totally plastered.

He never got through to the première.

Never.

[laughter]

But he did take part in dress rehearsals and more than once gave me a good tip. For example: “Olenka, take off that red on the right side. It’s not necessary.” I trusted him very much, he would give me brilliant tips. When we were doing Lulu with Michał Kwieciński, I made a lift (Jerzy constructed it for me, because he was an architect)29. Lulu rode in that lift. Jerzy says: “Oleńka, wouldn’t it be wonderful if the lift was lined with fur inside.” Brilliant, this is naturally taken from Meret Oppenheim. We even toyed with the idea of making a fur lift, but in the end, we didn’t do it.

Jerzy was standing naked in the lift. Everyone knew I had a crazy bosom friend who has a hollow leg. That was what mattered to them. Everything else was unimportant because he was one of us.

In the late 1960s, Stajuda worked as a production designer for Polish television. And back then he introduced wire mesh used to make fences. Later, I also used this mesh to make entire stage designs.

But what was the point of getting naked?

Jerzy liked to scandalize. That is why, for example, he shocked the poet Julia Hartwig by showing her our nude photos from the beach.

We met when he was 46 and he seemed an old man to me. The first year after his wife Eve died, he spent lying stiff in an overcoat on the couch. His sister Krysia Wydro, aunts and grandmothers looked after the children. Mostly after Jan, because Jeremi was already bristling. He loved his mother insanely, and once, out of jealousy, he cut Jerzy’s paintings.

Jerzy got ravaged by alcohol when he still worked at the “Współczesność” journal, at that time everyone would drink heavily. The intellectuals could not bear the communist regime. After all, Grochowiak died of alcohol30. Jerzy didn’t drink himself to death only because of stomach problems. He had ulcers, they took him to the hospital, but he escaped anyway. He found that it helps him to go to a nudist beach and bask in the sun for hours. And he cured himself. But he kept on drinking, only much less.

In the second year after his wife’s death, he hit on the idea to learn Chinese. He took up a language course at the Chinese Embassy. He had been attending it determinedly two years. He learned a lot. He left a big notebook that they probably have at the academy. And now we can admire his beautiful calligraphy. Drawings, watercolors – they all have a Chinese stamp.

These are fascinating stories.

I remembered, you said that we need to say how Jerzy went to Zakopane. It shows his character. At that time, he worked for “Współczesność.” He was tasked with interviewing Tadeusz Brzozowski. He did a very beautiful interview that’s right here in this grey book31. There are even similarities between Brzozowski’s and Stajuda’s art. Jerzy admired him.

The gentlemen got to like each other very much and went on a trip to the mountains. Jerzy was in his beloved coat, he had a briefcase with him and he was wearing leather brouges. And it was in autumn, perhaps even in winter. They went to the mountains and disappeared. Jerzy didn’t tell me how they were found, probably by some mountain rescuers. They couldn’t go up high, because Jerzy wouldn’t have climbed high. He wasn’t an athletic type at all. He had utter disdain for sports.

In any case, they were broguth down from the mountains somehow, Jerzy was completely blue with cold. When he went to the train station, his ticket had long been invalid. Because they had been gone for three days. Vodka kept them warm, and then they tried to climb down. When Jerzy got on the train, they stamped “passenger lost in the mountains” on his ticket. And so he returned to his monthly’s office, or “Współczesność.”

It is a pity that Jerzy is no longer with us. If he could see the selections of our award committee (Stajuda Prize), I’m not sure how he would evaluate some of these texts.

He brought various circles together.

Yes, for example, he was friends with Anne Duruflé, attaché of the French Embassy, later wife of Marcel Łoziński (they have a son, Tomasz)32. Then she went back abroad again, to France. But she was here for two decades, during martial law she helped Polish artists, most of them associated with film and theatre. It was then that Andrzej Wajda went to France, as well as Andrzej Seweryn, Krystyna Zachwatowicz, and Daniel Olbrychski. She helped them find work there for two or three years. Some returned quickly, others stayed longer. Some were better off thanks it, others worse. She was a very frequent guest at our place. The secret police punctured the tyres in her car.

What was the genesis of the first home exhibition?

It wasn’t not my idea, I won’t definitely usurp it. It was Stajuda’s idea to gather friends and show his works. They weren’t exhibited in any galleries, as they had to be opposed after all.

This was at the time of the [artists’] boycott [of state galleries during marshall law].

Exactly! Some exhibited their works in churches, others at home. I don’t know if they did it in many homes.

In quite a handful actually. It was a phenomenon typical of the 1980s.

[parrot whistling]

You mentioned that a lot of musicians would drop by. Did Stajuda have musical education?

He was the son of a teacher, headmaster of a school in Falenica, on the outskirts of Warsaw. Somehow, they managed to survive the war there. During the expulsion of Jews from Falenica, Świder, Wawer (by the way, there is a huge stone monument commemorating Jews there), and from Otwock, the wind reportedly carried waves of burnt papers in the sky, as they were people who read books. And it all went up in smoke, with only scraps of paper flying around. Jerzy said it was one of his worst war memories. So it happened that they neither landed in any camp nor took part in the Warsaw uprising, because they weren’t fit for it, and Jerzyk was a little boy. He was born in 1936. They somehow survived in Falenica, but, of course, there was no school anymore. And then his father Kazimierz became the headmaster of the school again, and his mum was a teacher playing the piano, a bit crazy. Jerzy’s mom taught him the notes and to play the piano. She played him Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata.

This was the beginning of his love of music.

Music followed him throughout his entire life. In the last two years, he only played the piano and glued model airplanes together with his younger son Jan.

His mother’s name was Barbara. She loved Jerzy, who had a younger, very wise sister, Tereska (she became an Arabist). Recently, she has married a professor who built ships.

Like Stajuda.

Exactly! These ships are still there, after all. He built them according to, what he called, morphology of ships. Everything was carefully measured, masts etc. From matchsticks, needles, and pins. And he built them on the porch in Brok, where he spent a very boring holiday with the boys. He wrote such a beautiful text when the USSR invaded Czechoslovakia in 196833. And then he built another ship. At Jerzy’s place, there were always planes on the grand piano with a lid, and ships in a huge drawer.

What happened to his models?

Jan has them all!

Has anyone showed them?

Yes! At an exhibition at the Centre for Contemporary Art. Grześ Kowalski created a project titled Would you like to go back to your mother’s womb. He then interviewed many important artists. This exhibition also features a photo of Jerzy in a bathtub. He believed it was a good idea to return to the mother’s womb.34 I’d never want to!

Warsaw, Ola Semenowicz’s flat, 17 April 2021

Ola Semenowicz – born on 2 December 1941 in Clermont-Ferrand (France). She is a painter and stage designer. In 1966, she graduated from the Faculty of Painting and Graphics at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw and ten years later she completed her postgraduate studies at the Academy’s Faculty of Stage Design. At the end of the 1970s, she became involved with the theatre. She collaborated, among others with Krystyna Meissner, Antoni Libera, Janusz Nyczak, Tadeusz Łomnicki, and Bogdan Tosia. A long-time partner of Jerzy Stajuda, curator of his legacy, and standing member of the Jury of the Jerzy Stajuda Art Criticism Award.

1 Elżbieta Szańkowska – art historian, wife of sculptor Maciej Szańkowski (b.1938).

2 ZMP – an organization fashioned after the Soviet Komsomol, operating in the years 1948–1957. It served to indoctrinate youth in order to build a communist society.

3 Jerzy Stajuda (1936–1992) studied at the Faculty of Architecture of the Warsaw University of Technology (graduated in 1959).

4 Tadeusz Nyczek, Anioł w norze, „Gazeta Wyborcza” 1993, no. 218 (17 September); Tadeusz Nyczek, Jerzyk, „Znak” 1994, no. 11, pp. 57–66.

5 Piotr Morawski, Popołudnie słoneczne chodziłem jak po śmierci, documentary film, 1993.

6 Popołudnie słoneczne chodziłem jak po śmierci: STAJUDA. Obrazy, akwarele i rysunki. Fragmenty zapisków. Aneks: sprzęty z Wiejskiej 15, exhibition catalogue, Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, Warsaw, 17 September – 7 October, 1993. Exhibition curator: Aleksandra Semenowicz, cooperation: Ewa Gorządek, catalogue editor: Waldemar Baraniewski, exhibition design: Grzegorz Kowalski. Authors of the texts: Wojciech Krukowski, Joanna Pollakówna, Waldemar Baraniewski, Katarzyna Kasprzak, Marek Nowakowski, Władysław Terlecki, Włodzimierz Odojewski, Jacek Sempoliński, Aleksandra Semenowicz, Witold Lutosławski, Dorota Szwarcman. Musical pieces dedicated to Jerzy Stajuda: Paweł Szymański, Krzysztof Meyer, selection of Jerzy Stajuda’s texts: Waldemar Baraniewski, graphic design of the catalogue: Grzegorz Kowalski, photos from home exhibitions: Jeremi Stajuda.

7 Tadeusz Łomnicki (1927–1992) – theatre and film actor, theatre director; Janusz Nyczak (1943–1990) – theatre director; Krystyna Meissner (b. 1933) – theatre director.

8 Julia Hartwig (1921–2017) – poet and essayist; Artur Adam Międzyrzecki (1922–1996) – poet, translator of French and English language literature; Jerzy Grzegorzewski (1939 – 2005) – director and stage designer; Władysław Lech Terlecki (1933–1999) – writer and screenwriter; Rajmund Kalicki (b. 1944) – writer, translator, expert in Latin American literature and the works of Witold Gombrowicz; Marek Nowakowski (1935–2014) – writer, publicist, screenwriter.

9 Paweł Szymański (b. 1954) – contemporary composer; Tadeusz Wielecki (b. 1954) – composer, bass player, long-term director of the “Warsaw Autumn” International Festival of Contemporary Music.

10 Witold Lutosławski, Grave: metamorphoses for cello and piano – a composition written to commemorate Stefan Jarociński, first performed at the National Museum in Warsaw on 22 April 1981.

11 Jerzy Stajuda. Obrazy, akwarele, rysunki, 1 December 1988 — 2 January 1989. Photo documentation of the exhibition: https://zasoby.msl.org.pl/mobjects/view/467 (access 2 September 2021).

12 The painting in question is titled Zone (1990). See http://www.lutoslawski.org.pl/pl/person,68.html (access 2 September 2021).

13 Obraz. Pocztówka urodzinowa dla Samuela Becketta, 1986, oil on canvas, Museum of Art in Łódź. See https://zasoby.msl.org.pl/arts/view/4600 (access 2 September 2021).

14 The person in question was Fr. Prelate Antoni Stajuda (1910–1995).

15 Aleksander Wojciechowski (1922–2006) – art critic and art historian. In 1950–1991, he was head of the centre for research and documentation of contemporary art, in 1979–1998 he was president of the Polish Section of AICA.

16 International Association of Art Critics (AICA) – an organization founded in 1950 under the patronage of UNESCO.

17 Ryszard Stanisławski (1921–2000) – art historian and critic, director of the Museum of Art in Łódź in 1966–1990.

18 Grzegorz Kowalski (b. 1942) – sculptor, performer, installation artist, university teacher, and art critic.

19 Katarzyna Kozyra (b. 1963) – studied at the Faculty of Sculpture of the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw in 1988–1993.

20 Dorota Szwarcman (b. 1952) – music critic.

21 Katarzyna Kozyra. Casting, ed. Maryla Sitkowska and Hanna Wróblewska, exhibition catalogue, Zachęta National Gallery of Art, Warsaw 2010–2011, pp. 25.

22 Miesięcznik Literacki was published between 1966 and 1990. The monthly’s editor-in-chief was Włodzimierz Sokorski (1908–1999), in 1952–1956 minister of culture and art, one of the main figures responsible for introducing socialist realism in Poland.

23 Jerzy Kalina (b. 1944) – installation artist, performer, stage designer.

24 Maciej Gutowski (1931–1908) – historian and art critic; Danuta Lutosławska (1911–1994); Edward Wende (1936–2002) – lawyer, in the 1970s and 1980s defence counsel for illegal opposition members in political trials; Andrzej Dłużniewski (1939–2012) – painter, graphic designer, poster artist, installation artist, writer; Józef Patkowski (1929–2005) – founder of the Polish Radio Experimental Studio.

25 Krzysztof Kelm (b. 1947) – director and stage designer.

26 Wojciech Freudenreich (b. 1939) – painter and graphic artist.

27 Michał Kwieciński (b. 1951) – Polish screenwriter and director.

28 Jacek Baszkowski (1935–2004).

29 The premiere of the play took place on 12 July 1987 at the Wilam Horzyca Theatre in Toruń.

30 Stanisław Grochowiak (1934–1976) – poet, playwright, columnist, and film screenwriter.

31 Jerzy Stajuda, Rozmowa z Tadeuszem Brzozowskim, „Współczesność” 1966, no 3, p. 5 (reprinted in: Jerzy Stajuda, O obrazach i innych takich, eds.: Jola Gola i Maryla Sitkowska, Muzeum Akademii Sztuk Pięknych, Warszawa 2000, pp. 239–241).

32 Marcel Łoziński (b. 1940) – film director and documentary film-maker.

33 See Jerzy Stajuda, List do Grzegorza Kowalskiego w odpowiedzi na zaproszenie do udziału w wystawie „Magowie i mistycy” [c. 1990], in: idem, O obrazach i innych takich, op. cit., p. 466–467. The letter includes text from 1968.

34 Stajuda’s answer to Kowalski’s question Would you like to return to your mother’s womb? was first shown by Emilia and Andrzej Dłużniewskis at their Galeria Piwna 20/26 in 1988.