No. 35

Between Collectivism and Individualism —

Japanese Avant-garde in the 1950s and 1960s

Maria Brewińska

The exhibition of Japanese avant-garde art of the 1950s and 1960s organized at Zachęta is particularly important to me. The beginning of its story is my long stay in Tokyo, combined with my studies, in the mid-1990s. I remember experiencing culture shock in my first few months in the city, enhanced by intensive Japanese language learning. I had previously only known Japan from classic films seen in arthouse cinemas. From the perspective of a newcomer from Poland just after the fall of communism, this country seemed so different as to be unreal. I remember well my first trip to Tokyo; I had to get a connecting flight in Frankfurt, where already at the airport there were a lot of Japanese people (in those days there were far fewer foreigners traveling to Japan). The long flight was an intense experience, not the least because of the passengers smoking on the plane. Then there was the long drive from Narita airport through Tokyo, during which I saw the chaotic structure of the city crammed with mid-sized architecture from the level of the flyovers, ending in my room with a view of Mount Fuji. In the years that followed, I traveled to Japan many times. The inconveniences of the long journeys were compensated for on arrival by the sights of kanji in the space, the sounds of the language, the smells of kare raisu (transliteration from “curry rice”) and all of the “Japaneseness,” particularly affecting the senses, so unique and different from the rest of the world. In this empire of signs, I studied everything: ancient art, modern art, architecture old and new, and even representations of Buddha in sculpture. I saw numerous exhibitions of Japanese art from every period, Asian art, sometimes hit Western exhibitions. It was a cognitive shock and a kind of cultural awakening.

In 2000, thanks to the support of Wojciech Krukowski, director of the Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art in Warsaw, and in cooperation with the Japan Foundation, the exhibition Gendai — Between the Body and Space. Japanese Comtemporary Art was realized. I remember that warm September morning, the Hasenkamp transport truck standing in front of the castle, and the accompanying extreme emotions. In the following years, also at the Ujazdowski Castle, we organized an exhibition by Tadashi Kawamata (2001) and his site-specific project of an archaeological nature, which consisted in reconstructing the historic cellars of the castle (2002). In 2004, Yayoi Kusama’s psychedelic installations were exhibited for the first time in Poland, at the Zachęta gallery. Studying in Japan helped me become familiar with art from other parts of Asia, which, due to its cultural and geographical proximity, is still often shown there today.1 Presentations of Japanese and, more broadly, Asian art coincided with the worldwide interest of institutions and the art market, as well as large biennial-type exhibitions in the region; in the case of Japan, the first exhibitions were held as early as the 1960s. Undoubtedly, however, Japanese art was embedded into the mainstream narrative of art history, reflected in the large-scale presentations of Japanese art.2 By the early 1990s, Japan already had a significant art scene and could boast a sophisticated tradition of avant-garde art, the elaboration of which continues in various research communities. Among the groups active in postwar Japan, the Gutai Art Association is the most popular collective, being particularly popular in Western museums and galleries. In the last decade, Reiko Tomii,3 a leading scholar of post-war Japanese art and author of many insightful texts and publications, has expanded her research to include other collectives such as Hi Red Center, The Play, and GUN (Group Ultra Niigata). In Japan, Raiji Kuroda is one of the experts on artist collectives in Japanese post-war art.4 We should also mention Reiko Kokatsu’s research and her ground-breaking exhibitions and publications on the involvement of women artists in post-war Japanese avant-garde movements.5

This exhibition was organized at a special moment. Firstly, it was developed in the difficult time of the pandemic and its fate was uncertain until the last moment. Secondly, it appears at the beginning of decade which has already seen (after many trials and tribulations) the Tokyo Summer Olympics (2021) and will see Expo 2025 in Osaka. In the 1960s, Japan also witnessed similar global events that can be considered landmarks in the country’s postwar history: the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, the 1970 Osaka World, and Expo’70. With these spectacular events, which were the result of rapid economic growth, Japanese society entered a new phase, which after Expo’70 took on yet another dimension. Since the early 1950s, transformations in Japan had taken place in every dimension of political, social, and cultural life—including the art world. Postwar avant-garde artists felt liberated from their former ideologies and built new foundations for art far removed from conventional forms and hierarchical organizations. The works of the participants of groups such as Democrato Artists’ Association, Jikken Kōbō, Gutai, and Kyūshū-ha (Kyushu School) were presented at independent exhibitions such as Japan Independent and the Yomiuri Independent Exhibitions, among others. The 1960s can be considered revolutionary due to the increased use of performance in public space, led by the collectives Neo Dada, Hi Red Center, Zero Jigen (Zero Dimension) and Banpaku Hakai Kyōtō-ha (Expo’70 Destruction Joint-Struggle Group). At the end of this decade, when The Play, GUN, or Bikyōtō (Bijutsuka Kyōtō Kaigi, Artists Joint-Struggle Council) formed—groups that operated in an intimate way, sometimes in retreat from civilization—the revolutionary drive was dying out, and new energy was accumulating in the material-focused minimalist trend called mono-ha.

The title of the exhibition touches on issues often raised in the study of Japanese art and culture, as well as in the description of social behavior in Japan. In terms of the traditional division between individual and collective cultures, Japanese culture is seen as the latter, because within it there are certain expectations of the individual functioning in a group. These relate to issues of socialization, obedience, alignment with the collective for the common interest, and cooperation motivated by a sense of duty. Undoubtedly, in Japanese society, unlike in Western culture, the individual is seen as part of the collective, and often the creativity of the group proves more important than the potential of its members. In postwar Japan, as modernization and westernization progressed, European and American customs influenced the traditional models of its society. They contributed to the individualization of the Japanese environment, though it remained far from the Western model. It is assumed that one reason for this is the long-established collectivism, as well as the lack of individualistic traditions in Japanese culture, which are considered to be contrary to traditional norms and values.

It is important to look at whether the collective nature of Japanese culture influences artistic practice. Individualism in the field of artistic creation seems to be an obvious attitude, just like the fact of the existence of various group formations since the beginning of modernity in art and the collectivism widely practiced in the globalized and postmodern world in various environments and cultures. Collective actions are almost always the result of breaking down the conventional principles of art production and distribution. They offer alternative possibilities for new art practices and to forge a new relationship between art and social forces through engaged and communal actions (especially in today’s times). Reiko Tomii sees collectivism as a tool that can be used to trace the development of modernism in Japanese art. Her essays offer comprehensive explanations of the sometimes convoluted organizational structures of the art world in Japan (partly because of language), as well as terminology and distinctions between various linguistic entities and their counterparts. The primary terms refer to art created in the period since before the war: these are kindai bijutsu (modern art before the Second World War), gendai bijutsu (modern art after the Second World War until the 1970s), and kontenporari ato (contemporary art, from the 1980s to the present). Other useful terms relate to the group activity conducted by numerous bijutsu dantai (abbreviated dantai) art associations. Active from at least the mid-nineteenth century to the present, these groups are hierarchical and conservative in their structure, stage art salons and competitions, and their members adopt similar techniques and aesthetics. Since the post-war period, smaller groups (shūdan), marginal and less formalized, have also been active. Dantai dominated the prewar art world, and the government-run Bunten Salon (organized by the Ministry of Education since 1907) set the tone for the rest. As a side note, the 100th anniversary of Bunten’s first exhibition was celebrated at the National Art Center in Tokyo in 2007. Bunten has evolved over the years, renamed Teiten (Exhibition of the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts), Shin Bunten (New Bunten), and after the Second World War, Nitten (Japanese Art Exhibition). It is still held today and showcases works in nihonga (Japanese-style painting) and yoga (Western-style painting) types, sculpture, crafts, calligraphy, and more. This highlights how strong the tradition of groups—or rather artistic associations, whose members practice a similar type of art—persist in Japan despite the transformation. They still coexist today with contemporary forms shaped by the worldwide evolution of language and art practices, and their long persistence can be considered a global phenomenon. Much of society is still attached to the Japanese-style “academic” creativity associated with dantai, which, let us emphasize, is not based on progress and novelty, but rather on the maintenance and improvement of established genres and forms of expression. Tomii writes of it as an inherently “non-evolutionary” artistic expression typical of dantai; interestingly, she sees the entire dantai system as a partly positive and socially important phenomenon, particularly in the early twentieth century (until the outbreak of the Second World War), which allowed modernism to embed itself in Japanese art devoid of its inherent tradition, and to evolve separately from it. The extended period of assimilation and development of modernism within dantai allowed the Japanese community to become accustomed to the new language of art. The critic writes:

In the global study of collectivism, Japan presents a particularly challenging case of constructing its local history, for the phenomenal proliferation of artists’ collectives makes it at once a “land of collectivism” and a “museum of collectivism.” Japan is a land of collectivism because it has produced literally hundreds of artists’ groups since the late nineteenth century, which as a whole constitute a main engine to propel the evolution of its art practices and institutions in the past century. If twentieth-century Japan was a land of collectivism, twenty-first-century Japan is a veritable living museum of collectivism, in which assorted modern modes of collectivism that historically arose can still be found in active operation.6

Collectivism, Tomii argues, is inherent in the DNA of Japanese art and early modernism, and this DNA has its own unique structure, marked by a kind of dualism. Probably the most important event in the transformation of Japanese art after the war was this split in creative practices, which took place during and was reinforced by the radical changes shaping a completely new society, forcing the search for forms and strategies of artistic expression adequate to the times.

The late 1940s marked a radical transformation in Japan: the country was first under U.S. occupation (until 1952), and then suffered the consequences of the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security Between the United States and Japan (signed in 1951; known as Anpo for short). The treaty cemented the military alliance between the two countries and laid the foundation for Japan’s economic growth in the following years, but it also sparked a wave of protests that lasted more than a decade. Although some progressive reforms initiated the transformation of Japanese society, soon a confluence of events such as the American Cold War strategy, the Korean War (1950–1953), and the establishment of military bases throughout Japan led to it slowing down. It was a tumultuous decade, with memories and traumas of Hiroshima and Nagasaki surfacing in addition to ongoing conflicts. Post-war artists who continued pre-war traditions produced work that was not only incompatible with the trends of international art, but also distant from the reality of a physically destroyed country and a nation exhausted by war. In contrast, painters who had their roots in the avant-garde movements of the pre-war period, such as Masao Tsuruoka and Nobuya Abe, conveyed the heavy post-war mood in portraits of traumatized people. Tsuruoki’s Heavy Hand (1949) depicts a male figure whose exaggerated arms obscure his entire body, shown against a background of overwhelming, cubic structures. Inspired by an encounter with a homeless man living in the underground of Ueno Station (a district of Tokyo devastated by air raids during the war) and considered pivotal for its time, the painting shows a deformed body symbolizing the spiritual oppression of the Japanese in the post-war era. Tsuruoka served in the Imperial Japanese Army during the Nanjing Massacre (1937). Throughout his years of poverty, he never gave up painting, and as part of his rebellion against wartime control of artists, he co-founded the Shinjinga-kai group (New Artists Painting Association, 1943). He later belonged to Jiyū Bijutsu Kyōkai (Free Artists Association, 1937–1951) established by Ei-Q (founder of the Demokurāto Bijutsuka Kyōkai (Democratic Artists Association in Osaka, 1951). Abe Nobuya came to attention at an early age through his 1937 collaboration with the influential critic and writer Shūzō Takiguchi. In the prewar years, he was a member of the Bijutsu Bunka Kyoka (Art Culture Association). While he experimented with surrealism he was also a photographer who belonged to the Association of Avant-Garde Photographers. The image of human skeletons in the painting Myth A (1951) from the Hunger series is in keeping with the style of martyrological figuration in painting of the time, in which surrealist distortions illustrate postwar poverty and the psychological condition of society. His experiences of war also informed his work; he began writing Hunger after spending six years in the Philippines during the war, where he worked as a reporter for the Japanese military. Among post-war Japanese graphic artists, it is worth mentioning the name of Hamada Chimei and his series Elegy for a New Conscript (1951–1960), which is regarded as the most demonic and cruel depiction of wartime experiences and post-war trauma, based on the artist’s experiences of military service during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945). Critics point out that Chimei’s copperplates—including the harrowing Sentinel (1954), in which a soldier aims a rifle at his own throat, and Landscape (1952), with an impaled figure—are like medieval representations of torture.

The period of 1946–1950 saw the “Realism Controversy,” a lively debate about the role of the artist in society, art forms, and the social significance of art in a recovering culture. The participants in the debate were representatives of different groups of artists and intellectuals: social realism (Fumio Hayashi and Kiyoshi Nagai), modernist realism (Hijikata Teiichi), and avant-garde realism (Takachiyo Uemura, Tarō Okamoto, and Kiyoteru Hanada). They discussed art world reforms, value systems, and sought new aesthetic theories and practices to connect art and society at such an important time.7 There was a call for new forms of realism, and this need was met by reportage painters. This informal group of left-wing artists painted canvases with similar themes (in a kind of interventionist painting) inspired by social, political, or military events. The Annual Japan Exhibition (Nippon-ten, 1953–1959), co-organized by Seinen Bijutsuka Rengō (Youth Artists Alliance) and Zen’ei Bijutsu-kai (Avant-Garde Art Association), became an important platform for the work of this movement. The reportage painters used a style of grotesquely distorted figuration to reproduce images of dead or tormented bodies that was popular in Japanese art (as well as in European art) of the period, reflecting human vulnerability during and after the war. In the early 1950s, Socialist Realism was practiced all over the world, and images in this style were easily understood by everyone. A variation of it also appeared in Japan, combined with surreal styling and grotesque deformation. The Tale of Akebono Village (1953) by Kikuji Yamashita, another former soldier struggling with the traumas of war, is an iconic example of the trend. The painting is an account of a trip to an impoverished village in the remote Yamanashi Prefecture (where the artist traveled at the behest of the Cultural Brigade of the Japanese Communist Party in 1952) and depicts the inhuman conflicts in post-war society. Some reportage painters saw these conflicts as a state of civil war, including Shigeo Ihii, author of the painting State of Martial Law (1956), who was regarded as a creator of allegorical works exploring his country’s difficult and troubled subconscious. They reveal the humiliations of occupation, political and military entrapment, and social inequality. His works are abstract labyrinths characterized by emptiness and resignation, with an atmosphere like that of the novels of Jean-Paul Sartre or Albert Camus, Japanese translations of which reportedly filled the shelves of the artist’s apartment.

Cartoonist Tatsuo Ikeda was just fifteen years old when he became a kamikaze pilot. Japan’s defeat spared him a suicide mission, but the American occupation policy forced him out of teacher training school. Ikeda created a series of drawings depicting bombs, beasts, and monsters—deformed human-like creatures. His 1953 work was inspired by protests in the coastal town of Uchinada, where the U.S. military had turned the beaches into an artillery range. In 1954, he created a well-known series of works relating to a fishing boat irradiated by fallout from a U.S. thermonuclear bomb at Bikini Atoll (1954), alluding indirectly to the toxic effects of Japan’s rapid industrialization. In his paintings, distorted figures are depicted in a barren post-nuclear landscape. Together with Shigeo Ishi and On Kawara, Ikeda formed the Seisakusha Kondankai (Producers Discussion Group), which pursued a new formula for realism. Nakamura Hiroshi, trained as a reportage painter by the Japan Art Alliance (a post-war art group advocating realist painting with political themes), developed innovative formal strategies and constructed chaotic, futuristic spaces that reflected the transformative dynamics of Japan at the time. Beginning in 1960, he painted a series of paintings in stark red as a record of the bombing in his hometown of Hamamatsu, and in 1964—the year of the Olympics and the launch of the shinkansen (a bullet train that helped Japan seem futuristic)—he created the work Sacred Fire Relay (1964) for an Olympic-themed exhibition sponsored by Mainichi Shimbun.

The grotesque figuration of disfigured and dismembered bodies in reportage painting depicted the doom-laden post-war reality. At the same time, other artists attempted to capture the paradoxes of reality in paintings that were conceptual and somehow “indifferent” to the general atmosphere. On Kawara, who made his debut at this time, became famous for his series of twenty-eight drawings, Bathroom (1953), shown at the 1st Japan Exhibition (1953). His works depicted the atmosphere of the 1950s and met the demands that emerged from the debates of the time, but their character was distinctly different from the conventional processes of figurative painting, and the dense representations that came from the brush of the “reporters.” This series, intriguing compared to other works of the time, shows figures that resemble embryos or bacterial forms, whole and dismembered, in various configurations, in a cramped bathroom space. The drawings have been interpreted as depictions of the “mental numbness,” trauma, and anxiety experienced by Japanese society as a result of socio-political upheaval.

Tarō Okamoto, a versatile artist, art theorist, and writer known for his avant-garde paintings, public space sculptures, and murals, as well as for his theoretical writing on traditional Japanese culture and avant-garde artistic practices, participated from the beginning in the discussions about what type of realism was preferable—whether that be a variety of Socialist Realism, which dogmatically negated all avant-garde movements since impressionism, or an avant-garde realism that could better capture an uncertain reality, or another form altogether. Okamoto lived in Paris for ten years before the Second World War, where he was inspired by the work of Pablo Picasso, was interested in abstract art, and was a member of the international group Abstraction-Création from 1933 to 1937. After returning to Japan in 1940, he co-organized, among others, the group Yoru No Kai (The Night Society, together with Kiyoteru Hanada, 1947), aiming to integrate avant-garde art and literature. While in Paris, he painted in both an abstract style (to reflect the external world) and a surrealist style (to express the internal world), but soon came to believe that the two movements were incompatible. In 1947, he introduced the concept of polarism (taikyoku-ism), in which he proposed an acceptance of opposites and an aesthetic that directly opposed the visual unity and harmony of Japanese wartime painting. He also designed the Tower of the Sun (1970) as a symbol of Expo’70, representing on a monumental scale the past, present, and future of the human race.

The debate over realism set the stage for discourse in the following two decades, with an emphasis on new art disciplines and openness to experimentation. Leading the way were a fresh generation of critics that included Nakahara Yūsuke, Hariu Ichirō, and Tōno Yoshiaki, who published in newly established art magazines. Hand in hand with the renewed art discourse came the inauguration of more art museums: Museum of Modern Art in Kamakura (1951), National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo (1952), Bridgestone Museum of Art in Tokyo (1952), National Museum of Modern Art in Kyoto (1963), and the Niigata Prefectural Museum of Modern Art in Nagaoka (1964–1979), which organized exhibitions and reviews of current art as a response to the needs of the new democratic exhibition system. The emergence of new museum infrastructure influenced an unprecedented development of Japanese architecture in the following decades. The inevitable processes of change triggered support for the new creative communities, independent of the hierarchy of associations and the artistic establishment, and independent from the sponsorship of print media (the dailies Asahi, Mainichi and Yomiuri) and large department stores (a Japanese specificity). In the post-war period of the Shōwa era (1926–1989), specifically in the early 1950s, the emancipation of the younger generation of artists, and sometimes the older generation, began in a new way in parallel with intense political and social changes. There was a kind of explosion of non-traditional artistic phenomena—popular culture penetrated the sphere of art, technological innovations awakened the passion for multimedia experiments, there were performative actions or happenings, interventions in public space, installation art, new painting or conceptual tendencies that sought to make the object of art disappear. At the same time, a mass audience was emerging. While these phenomena prompted a departure from traditional values and skills, pre-existing systems did not disappear. These fundamental changes led to the emergence of the modern artist who was far from creating sophisticated objectifying visions of the world. A new era began in Japan: that of gendai bijutsu—contemporary art8.

The exhibition at the Zachęta gallery builds a narrative based on works and artists who broke with the conventional understanding of art in post-war Japan, focusing primarily on the phenomenon of avant-garde art groups. Among these modern, often radical groups, other relationships based on independence were already being formed, and individualism and the free pursuit of self-identification were emphasized. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, a variety of collectives emerged in Japan, with varying degrees of formality and with varying lifespans. The 1950s saw the birth of such experimental groups as Jikken Kōbō (Experimental Workshop, 1951–1957, Tokyo) co-founded by Kitadai Shōzō and Katsuhiro Yamaguchi, and the aforementioned Gutai (Gutai Bijutsu Kyōkai, Gutai Art Association, 1954–1972, Osaka and Kobe) with Jirō Yoshihara as its leader. Although Gutai artists were primarily painters, they questioned the conventional understanding of the medium, which led them to expressive performances in which they used their bodies, confronting them with the material and expressive method of work. In Fukuoka on the island of Kyushu, the Kyūshū-ha (Kyushu School) was active, which shows that avant-garde activities had a wide reach beyond Tokyo. In the rhythm of the transformations of the 1950s, the revitalization and democratization of the rules of art making and making art available, the aforementioned Democratic Artists Association was established (1951–1957, Tokyo, Osaka and Miyazaki), whose members included Ay-O, Eikyū, On Kawara, Kōjin Toneyama, among others. Ay-o’s painting Pastoral (1953), with a marching crowd of captive mannequins, in the style of 1950s painting, is a commentary on the changes taking place in Japan, but also around the world.

The precursors of the post-war avant-garde sought expression beyond the traditional categories of painting and sculpture. Some creative practices initiated at the time as part of collective experiments foreshadowed future activities, such as the early multimedia research done by members of the Jikken Kōbō that gave rise to intermedia art. The group operated through a fusion of different disciplines. It consisted of young artists gathered around Shūzō Takiguchi, who believed that art must start from experimentation. Since 1951 the artists and composers who made up the group, among them Yamaguchi Katsuhiro, Shōzō Kitadai, and Tōru Takemitsu, combined various media (such as photography, music, theater, ballet, light, film) to create a total work that blurs the boundaries between genres. The group members sought to produce performance with synchronized sound, image, and movement, utilizing automatic slide projection. This improvisational technique produced one of the first audiovisual performances. The multimedia Jikken Kōbō group played a key role in the development of concrete and electronic music. In their style and way of working they resembled the realizations of the Bauhaus workshops, especially the collages and constructions of László Moholy-Nagy. In 1953 and 1954, they created the APN series, consisting of photographs (mainly by Kiyoji Ōtsuji) and sculptures and designs by Shōzō Kitadai commissioned by the weekly Asahi Graph.

The individualism of artists working within collective structures stemmed from a desire to transcend the framework of conventional modernism, as well as previously existing formulas for group coexistence. Gutai (active the longest until 1972), emphasized the individual’s creativity and subjective “autonomy” (Kazuo Shiraga). Known primarily for paintings, the group also produced outdoor events enriched with objects for play and interaction, as well as stage actions—performances using music, smoke, steam, etc. This activity culminated in a large multimedia program prepared for Expo’70 in Osaka. In the 1950s, Gutai artists began with concrete painting combined with uncontrolled gesture and performance. Kazuo Shiraga painted with his feet, rolling in the mud, questioning the limits of painting (Challenging Mud, 1955). Saburo Murakami did the same in his iconic performance during the first Gutai exhibition (Ohara Kaikan, Tokyo), which consisted in tearing several screens covered with paper using his own body (At One Moment Opening Six Holes, 1955). While Shiraga, Murakami, and Atsuko Tanaka—in her dress composed of hundreds of glowing lights (Electric Dress, 1956)—used the body as a medium, Akira Kanayama created automatic drawings and paintings with a device that spread paint on canvas, and Shōzō Shimamoto threw paint bottles at canvas. Zdzisław Jurkiewicz, a Polish theorist and artist, formulated a reflection on the conceptual meanings of such Gutai activities:

For action painting painters—we emphasize—it was not just a dispute over the finished product, over the painting: the coming time, like it or not, belonged to them. It was they who—for the first time in the thousand-year history of painting—had the courage to declare that what was most important above all was the spontaneous impulse, deciding HOW to manifest one’s presence in a painting, and not what was “made visible” in it. This prophetic lesson—as we know it—was taken almost to the brink of insanity by the Japanese Gutai group, and one of the paths leading to the happening led from it.9

Yirō Yoshihara advocated avoiding imitation and seeking an autonomous art language. In the eighteen years Gutai was active many artists passed through, employing a variety of heterogeneous practices which resonated individually within the community, developing its diversity and enriching the dialog around the “collective spirit of individualism.”10

Local transformations in the arts were accompanied by the formation of both group and individual practice and the development of gendai bijutsu consciousness. Kyūshū-ha,11 a group that was part of the underground and anarchist art of the 1960s (including Mitsuko Tabe, Mokuma Kikuhata, and Osamu Ochi), held independent exhibitions in Fukuoka, Kiuiu, and introduced avant-garde art to the region, but in public spaces and outside institutions. The group created installations, performances, burned canvases, used found materials such as amber, put together assemblages from garbage, and used tar. Exhibitions of its main representatives were also held in Tokyo, in two important galleries, Ginza and Minami, under the slogan “attack on Tokyo.”

The Neo Dada and Hi Red Center groups are part of the so-called “anti-art” movement—a term that emerged around 1960 to describe revolutionary experiments that, through the negation of traditional concepts, free art from constraints by bringing it into real life. Neo Dada (Neo Dadaism Organizer[s], 1960–1962, Tokyo) had been active since the 12th Yomiuri Independent Exhibition (March 1960). The associated artists held shows at Yoshimura’s studio, the White House, one of the first buildings designed by architect Arata Isozaki. Tetsumi Kudō and Tomio Miki participated in the group’s activities but never officially joined. Along with Yayoi Kusama, they were described as “obsessive artists”: Kudō, known for his obsession with phalluses, created subversive works exploring the subconscious, while Miki replicated the ear motif in every work. In April 1960, the Neo Dada exhibition was held at the Ginza Gallery in Tokyo, at which a manifesto edited by Shinohara was announced. Most of the group’s events and exhibitions were covered by the media, whose curiosity was aroused by anarchic, obscene, and destructive happenings not always associated with art. Shūsaku Arakawa, who created coffin-like objects with cement blocks inside, was eliminated from the show for alleged aestheticism. His work stood apart from the spontaneous actions organized by Ushio Shinohara boxing his canvases (painting with his hands) in public places (Boxing Paintings, 1960). Later, Shinohara created works in the pop art style, including Coca-Cola Plan (1964), a sculpture that echoes Robert Rauschenberg’s work Reproduction of Coca-Cola Plan (1962), an act of appropriation art. In the spirit of pop art, he processed well-known ukiyo-e prints from the Edo period (Doll Festival, 1969). The imitation of other artists was the turning point that prompted the artist to move away from anti-art toward creating art objects. Tetsumi Kudō (who moved to Paris in 1962), a Neo Dada sympathizer who was never affiliated with the group, created sculptures, installations and performances using readymade objects and the motif of cages, phalluses, flowers or his own portraits (Mother Complex Paradise, 1980), which were examples of the so-called abject art. His assemblages were characterized by a grim humor that referred to the condition of life (Votre Portrait [Your portrait], 1963). In the late 1960s, he became famous for his bimorphic assemblages alluding to the problem of environmental degradation. He came across as a critic of consumerism and political conformity.

Many works of the Japanese avant-garde have not survived. Some were reconstructed during the artists’ lifetimes for exhibitions (e.g., Tanaka’s Electric Dress, reproduced in 1986) or the art market. Actions, happenings, exhibitions, and other events are known from the documentation of photographers such as Mitsutoshi Hanaga, Minoru Hirata, Kiyoji Otsuji, Shigeo Anzai, Murai Tokuji, or through anonymous materials (including Gutai’s extensive documentation). Hanaga recorded, among other things, the action of Genpei Akasegawa wandering down the street with a large printout of a thousand-yen bill (Morphology of Revenge, 1963). By the end of his life, Akasegawa was already regarded as an icon of Japanese modern art. Early on, he was involved with two groups, Neo Dada and then the Hi Red Center. From the period of his membership in the former comes the giant-sized Sheets of Vagina (1951/1994)—a vagina made from crushed car tires. It was shown at one of the last editions of the Yomiuri Independent Exhibition (1961), which was soon closed for fear of controversial works and content in view of the upcoming Olympics. Akasegawa came into the public spotlight precisely because of his work The Thousand-Yen Note Incident, in which he used a replica of the obverse of a banknote on a solo exhibition announcement he sent to friends by mail. Over the following months, he made several thousand reproductions of the work, burning some as part of the performance and using others to wrap various objects. In 1964, charges were brought against him for violating a currency and securities imitation control law. The case went to court and the artist received a three-month suspended sentence. The story provoked a high-profile debate about censorship and free speech in the arts.

In 1963, along with Jirō Takamatsu and Natsuyuki Nakanishi, Genpei founded the Hi Red Center group. The artists acted collectively as a limited liability company, using a red exclamation point as their logo. They organized several high-profile happenings in urban spaces, making the public sphere a place of permanent presence of art. In 1962, they performed actions on the Yamanote Line city train (Yamanote Line Incident) using Nakanishi’s so-called compact objects, Takamatsu’s looped ropes, eggs, and chicken feet etc. Absurd activities in response to the flurry of changes at the time broke up common behavior and boredom. Another famous action involving street cleaning (Be Clean! and Campaign to Promote Cleanliness and Order in the Metropolitan Area, 1964) ironically referred to the cleaning of the city space in preparation for the Summer Olympics in Tokyo. The Dropping Event—dropping everyday items from the roof of a building—could be interpreted as a critique of the increasing consumerism. In 1963, HRC members organized a campaign called Shelter Plan (1964)—they rented a room at the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo and invited selected people to organize one-man nuclear shelters. The participants, including Yoko Ono and Nam June Paik, were photographed from all sides (including the top of their heads and the bottoms of their feet) to create foldable models of their figures; medical cards with detailed physical data were also created. The seemingly nonsensical action was a reference to the traumatic experience of war.

Actions and happenings organized collectively in public places became the mark of Neo Dada, Hi Red Center, but also Zero Jigen and Japan Kobe Zero. This was an entirely new element, bringing a radical change from the collective actions of the dantai associations. The new strategies stemmed both from the need to demonstrate their views in a direct way, which was a novelty at the time, but they were also derived from a critique of institutions and exhibition systems, although all the newly formed groups also functioned in official and institutional circuits. Intimate forms of action were realized by Naoyoshi Hikosaka and Michio Horikawa, while others created happenings surrounded by nature, far from urban spaces (Tadashi Maeyama, Horikawa). Hikosaka co-founded Bikyōtō (Bijutsuka Kyōtō Kaigi, Artists Joint-Struggle Council), a radical art and political group, and from 1970, he was active in institutional criticism. He launched the series Floor Events (1970–1975), in which he covered the tatami mat floor in his apartment with white latex, and the process of the paint drying—about a week—became a kind of exhibition. These activities continued until 1975, when the artist’s participation in the Paris Youth Biennale ended with the tatami mats being confiscated and burned by Japanese customs while attempting to ship them back home. The conceptual Mail Art by Sending Stones series (1969–1972) by Michio Horikawa, co-creator of GUN (1967–1975) was influenced by mail art. The Shinano River Plan: 11 (1969), one of the first projects in the series inspired by the Apollo 11 moon landing (1969). Horikawa’s action referred to the space race and anti-war protests. Michio Horikawa and Tadashi Maeyama as the GUN group were also, among others, the authors of the landscape happening Event to Change the Image of Snow (1970) on the Shinano River.

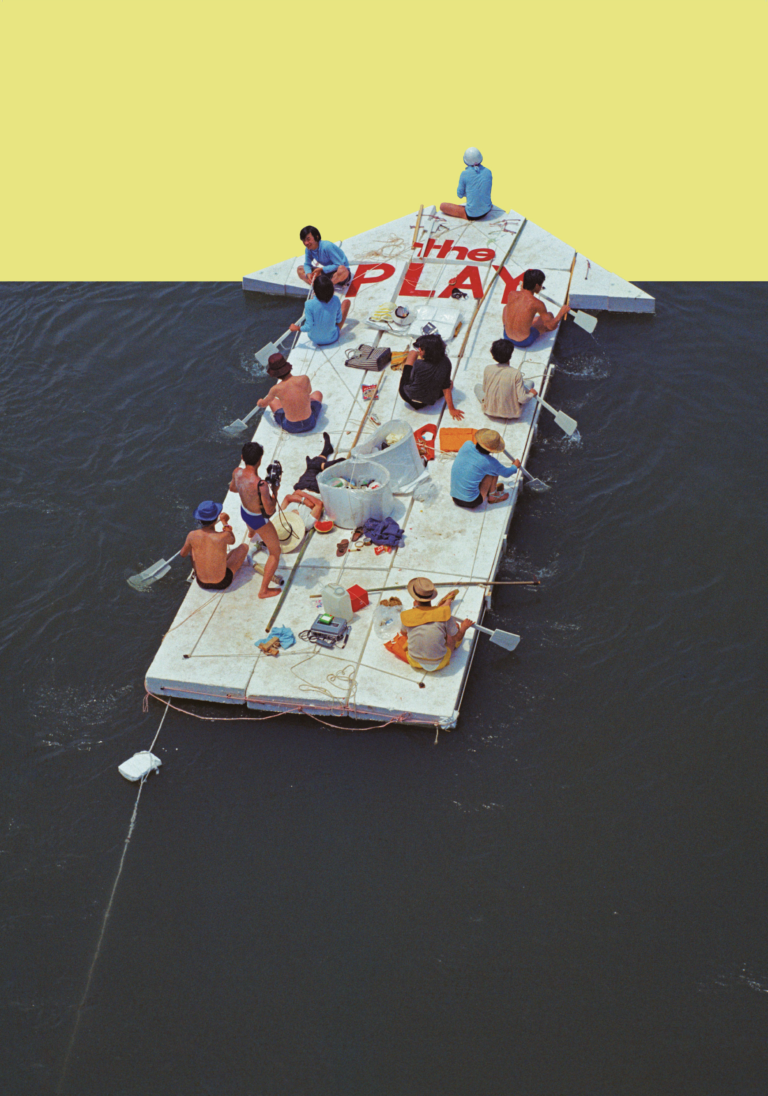

The Play Group, led by Ikemizu Keiichi, is still active today. Unlike other groups, it functions as a commune that strives to maintain its existence as a community. Its first action was Voyage: A Happening in an Egg (1968)—the dropping of a huge egg into the Pacific Ocean near Shionomisaki in Wakayama Kansai Prefecture, the southernmost point of Japan’s main island. “The egg carries the image of liberation from all the material and mental limitations imposed on us living in modern times.” In the project Current of Contemporary Art (1969), the group members made a twelve-hour journey from Kyoto to Osaka on a raft shaped like a giant arrow. Play created many projects in the following decades, and in fact this group was the only one that managed to realize and maintain a form of social collective based on community action over a long period of time.

For more than two decades after the end of the Second World War, Japanese culture struggled with political and social transformation to finally meet the rapid pace of global artistic change, although its assimilation and development proceeded in the country on its own terms. The dynamic changes resulted partly from political circumstances and partly from the desire to catch up with Western culture, while at the same time there was an ongoing debate about preserving cultural distinctiveness. The Japanese avant-garde took various forms: from modern and pro-local (specific only to Japan), through imitative, to more universal, developing new transcultural attitudes. It was the two eponymous decades, although still anchored in the experiences of war and post-war political ferment, that became the period in which Japanese culture was redefined. This was also done thanks to the great creativity and innovation of artists from different generations. The resurgent prewar establishment and the young artists expressing themselves outside of it set the specifics of 1950s art with little reliance on Western influence, a fact that changed in the following decade, a boom of national economic prosperity and flourishing international exchange. At the same time, there was a parallel process of moving away from international versions of modernism and formalism and a move towards local sources. Moving beyond modernism, the avant-garde increasingly created art that was, so to speak, post-Western. Although the end of the 1960s was still marked by protests against Expo’70 and the rapid modernization of the country, as well as by individual gestures of protest against the abandonment of Japanese traditions (the most characteristic expression of which were the suicides of Yuko Mishima in 1970 and of Yasunari Kawabata two years later, as a protest against and an expression of longing for the old, idealized image of Japan), another phase of social change soon came, beginning a new stage of Japanese art that focused on the autonomy of the individual, the exploration of private experience, and questions of identity. In both decades, a distinctiveness emerged that still characterizes Japanese culture today.

By the end of the 1960s, avant-garde movements were losing relevance and the energy of collective activism was burning out, although a few groups were still active by the end of the following decade. The longed-for revolution did not happen. With the 1964 Tokyo Olympics and the Osaka World Exposition (which brought a corporate culture to Japan that had been previously unknown), a highly consumerist society was taking shape. The turn of the 1960s and 1970s thus marks the boundary between the artistic experiments of the postwar era and the artistic culture of capitalist conformity that had taken root in Japanese society and against which anti-modernist movements protested. This is brilliantly demonstrated by the photographic work of the authors of the legendary magazine Provoke from 1968–1969, which challenged the popular practices of 1960s photography. With their rough and blurry photographs, they wanted to penetrate the crevices of authentic reality, as opposed to “commodified” commercial photography, behind which stood only consumerism. The style of Provoke was quickly appropriated by the visual language of capitalism, but the importance of the creators the magazine brought together still cannot be overstated in the history of the medium.

In Japan, the desire to be reborn from the ashes of war created an unprecedented dynamic of change. The 1950s and 1960s, although socially and existentially challenging, became the arena of unprecedented fundamental action and change and influenced the entire gendai bijutsu movement.

1 Zachęta Gallery presented successive exhibitions: New Zone — Chinese Art, Kim Sooja (both 2003), the Red Flag explosion and the exhibition Paradise by Cai Guo-Qiang (2005), all curated by Maria Brewińska.

2 Reconstructions: Avant-Garde Art in Japan 1945–1965, Museum of Modern Art, Oxford, 1985–1986; Japon des avant-gardes, 1910–1970, Musée national d’art moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, 1986–1987; Japanese Art After 1945: Scream Against the Sky, Yokohama Museum of Art, 1994, and more recently: Art, Anti-Art, Non-Art, Getty Center, Los Angeles, 2007.

3 Reiko Tomii, an art historian and curator based in New York, studied in Osaka and in the United States, and collaborated on the exhibition Yayoi Kusama: A Retrospective, Center for International Contemporary Arts, New York, 1989, and on the publication Japanese Art after 1945: Scream Against the Sky (1994); author of exhibitions, among others: Century City: Tokyo 1967–73 (Tate Modern, London, 2001), Art, Anti-Art, Non-Art (Getty Center, Los Angeles, 2007), Radicalism in the Wilderness: Japanese Artists in the Global 1960s (Japan Society, New York, 2019), Yutaka Matsuzawa: Towards Quantum Art (John Young Museum of Art, Honolulu, 2020).

4 Raiji Kuroda, Anarchy of the Body: Undercurrents of Performance Art in 1960s Japan (Tokyo: Grambooks, 2010).

5 Japanese Woman Artists Before and After World War II, 1930s–1950s, 2001; Japanese Woman Artists in Avant-garde Movements, 1950–1975, 2005, both Tochigi Prefectural Museum of Fine Arts, curated by Reiko Kokatsu.

6 Reiko Tomii, “Introduction: Collectivism in Twentieth-Century Japanese Art with a Focus on Operational Aspects of Dantai, positions 21, no. 2 (Spring 2013) (Durham: Duke University Press), p. 228.

7 See Justin Jesty, “The Realism Debate and the Politics of Modern Art in Early Post-war Japan,” Japan Forum 2014, vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 508–529.

8 Reiko Tomii exhaustively discusses the term gendai bijutsu in “‘International Contemporaneity’ in the 1960s: Discoursing on Art in Japan and Beyond,” Japan Review, 2009, pp. 123–147, www.academia.edu/8321491, accessed: 7.10.2021.

9 Zdzisław Jurkiewicz, “Sztuka w poszukiwaniu istotnego,” 1970, pp. 122–130, in Refleksja konceptualna w sztuce polskiej. Doświadczenia dyskursu 1965–1975, exh. cat., ed. Paweł Polit and Piotr Woźniakiewicz, (Warsaw: Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, 2000).

10 See Ming Tiampo, “Gutai Chain: The Collective Spirit of Individualism,” positions, Spring 2013, vol. 21, no. 2 (Durham: Duke University Press), pp. 383–415; idem, Gutai Decentring Modernism (Chicago: University of Chicago, 2011).

11 Raiji Kuroda, “Kyūshū-ha as a Movement: Descending to the Undersides of Art,” Review of Japanese Culture and Society, Josai University, December 2005.