No. 33

A story that can be shared

Ewa Łączyńska-Widz talks to Krzysztof Maniak

Ewa Łączyńska-Widz: What work have you done recently?

Krzysztof Maniak: As the year is coming to a close, I am slowly taking stock of it and finishing up my backlog of work. Some of them were started last year. This was the case with one of my recent works, which features empty escargot shells. It consisted in finding a thousand empty shells, which, contrary to my original intuition, turned out to be not an easy task, especially because I narrowed down the search area to Tuchów, where I live. Once I had found a thousand shells — and it took me nearly two months filled with intense walking — I selected and cleaned them. Prepared this way, they stayed with me for a year. During this time, however, I set myself the further task of inventing a thousand different instructions, scenarios for works relating more or less literally to my peculiar collection. After just a few dozen ideas, things got tough. Nevertheless, I managed to get to my intended thousand and, importantly, none of the ideas were repeated.

What were these ideas?

It’s hard to recall the exact wording of these instructions. They were things like grinding a thousand empty snail shells into dust. Bathing in a bathtub in the company of a thousand empty snail shells, arranging them in a straight line at metre intervals, filling them with marmalade, making them into the shape of a human silhouette — this is a nod to the work of Ana Mendieta. There were also the more improbable ones, such as returning all the shells to the exact same places I had found them, and the more complicated ones, which were like social activities: find a town in Poland with a thousand inhabitants and give each of these people an empty snail shell.

Which of these have you carried out?

The most mundane one, probably one of the first that came to mind. One September Sunday, my friend Bartek and I simply dumped these shells in the woods near my house. A white mound was created and can now be visited. Recently my dad found it when he was out mushrooming and took a picture. The shells have scattered a bit, but they are still there.

So you decided to give the shells back to nature.

Yes, it is common for me to return organic matter, which is a temporary prop in my work, to its original place of origin. It’s a kind of game, a confabulation about what we have come to call nature. In the forest where I left the shells, there are hardly any snails at all!

I made a similar gesture of return in my work with a found skeleton of a roe deer, an almost 80-year-old beech trunk, or field plants I dried for a whole year in order to place them, flattened like sheets of paper, in the original rural space and photograph them the following year.

In the case of the latter, I used a strategy referred to by Sebastian Cichocki in the context of my work, namely Robert Smithson’s 1968 A Provisional Theory of Non-Site, which deals, among other things, with the categories of ‘site’ — ‘non-site’ — ‘displacement’).

Which of these have you carried out?

The most mundane one, probably one of the first that came to mind. One September Sunday, my friend Bartek and I simply dumped these shells in the woods near my house. A white mound was created and can now be visited. Recently my dad found it when he was out mushrooming and took a picture. The shells have scattered a bit, but they are still there.

A fundamental practice in your work is walking. When did they appear and what are they to you?

Walking as the medium I currently use came naturally to me. For most of us, walking is our first and primary means of movement. I have always enjoyed walking, I didn’t use my driving licence for a long time, and my bicycle, although faster, has often been a handicap in exploring non-urban wilderness. A walk has a magic to it that is based on a fairly simple mechanism. We usually move at our own pace, adapting our walking speed to our condition or the difficulty of the terrain we’re moving through. The objectives, if there are any, do not appear suddenly — they get closer depending on our pace. They are assimilated by sight together with their background. In this way we get to know our surroundings, we involuntarily study them. We synchronise our thoughts with them, we enter into their successive layers and planes — sound, smell, etc. But back to your question — for me, walking is an adventure that I can treat myself to at any spare moment. Later on, you can set yourself some random goal — if only by spinning a bottle. That is best.

How long does this way of making art last?

I realised the importance of walks as a suitable — to put it in an ugly way — platform for creation a few years ago, while still at university. Even then I had met a whole plethora of artists who were coming out of this tradition. It was also influenced by books on walking that I came across during my study period, including Frédéric Gros’ A Philosophy of Walking, Henri David Thoreau’s essay ‘Walking’, Rebecca Solnit’s Wanderlust, as well as Lucius Burckhardt’s Why is Landscape Beautiful? and by Lucy L. Lippard’s The Lure of the Local, which I am currently working my way through. Although I mention these examples, in my case, the inclusion of walking in the vague framework of the creative activity I practice was not a preconceived plan. It’s just that on my walks, I practically always had my photography equipment with me. I like to capture rapidly changing places, moments, situations. For several years, I have been creating a series called Walks. In it, I explore the sculptural potential hidden in the actions of natural or non-human forces — decaying trees, rotting hay, sliding slopes, mysterious holes and trenches in the ground, all in an area narrowed down to the municipality of Tuchów.

And what limits do you impose on yourself other than that you move within a certain area?

For example, time — I usually apply the rule that the walk has to be closed in a unit of time, which is a day. Another rule is that at the end you I should go back to where I started. Using mechanised transport is not allowed — no rides. I often write down specific instructions or even walking scores that I test during my trips. I have quite a large collection of them.

You are focused in your walks and actions, which is the opposite of the modern day affliction of being quickly bored with everything. You are able to work on something for a long time and consistently finish it. Maybe Tuchów is no longer enough for most people, but for you it is still inspiring.

I draw on what is closest to me, what I have at hand. Although Tuchów and its outskirts cover only 22 km², I find everything here. I simply set myself challenges appropriate to the scale of the location. For example, I want to know all the streets in Tuchów, of which there are just over seventy. However, I already know that it will take me dozens of days to go through them all from start to finish, which will probably stretch over several years of walking. In addition, there are traditions and people here that I do not know but would like to know. I would like to give the proverbial high-five to every resident. Recently — and I must boast — I deciphered a riddle involving the name of a street patron. The street was named after Piotrowski, unknown even by his initials. I searched for information about him for a very long time, mainly online, but found nothing. The locals didn’t have much either. I was helped by my further cousin Wiktor, who is currently the vice mayor of the city. At my request, he found the full name of the street and the reasoning accompanying the request in the City Council resolutions. It was Stefan Piotrowski, an astronomer. This discovery has given me much joy.

Let’s go back to the Tuchów landscape for a moment. How would you describe it to people who have not yet been there?

Tuchów and its surroundings have very varied terrain — the city is located in the so-called Tuchów Depression, through which the Biała River flows. The valley is surrounded by hills and forests. The highest peak is Brzanka in Jodłówka Tuchowska, measuring 534 metres above sea level. It belongs to a whole range of hills that are part of the Outer, or Flysch Carpathians. I have a sense of a certain backdrop to this landscape, and it is also important that I can take it in with my gaze, which gives me a feeling of security and a certain cosiness.

You walk alone, you also do your own documentation of your activities in the field. Do you need an audience?

The audience constitutes the experience of art. It would be difficult to make things exclusively for the trunk— such strategies are possible, but then the viewer has no opportunity to get to know the creator during their lifetime. Therefore, I answer that yes, although my relationship with my audience is not easy, which I am aware of. In exhibitions, you can only see second-hand quotations from my performances, accessible live only to clouds, trees or other species. I go for walks alone — I need the solitude. But it happens that I invite other people to share my experience and I appreciate more and more the opportunity to pass on my discoveries on Tuchów routes.

When working on your exhibition, which was first shown at BWA Tarnów, then at BWA Bielska Gallery (curator: Sebastian Cichocki), we wondered whether it would be possible to transfer your experiences of close contact with nature to the gallery. The fears were unfounded. The public often recalls this exhibition as one of the most unique, emphasising that it allowed them to experience nature in a very close way. Many people add that after encountering your work, they learn to look anew at what surrounds us.

Indeed, presenting my practice in a gallery space is difficult. Both curators and gallerists know this. My works, which have a twisted status of work/not-work, are often created in long, repetitive or slowly evolving, incomplete series. This is because what is most important to me is the creative process itself, along with activating and contextualising. For example, the works with hay — which are the main parts of the exhibitions in Tarnów and Bielsko-Biała — began with hay from a meadow that I own. I remember when you were preparing for the exhibition, you came with Sebastian and Anna to my allotment, and you sat in the hay composition I had prepared — that’s how the idea was born. Every year since then, I have created a sculpture from this material. These works/not-works have a non-obvious form, reminiscent of strange furniture and sometimes humanoid-animalistic phantoms. On the other hand, it is a tribute to haystacks disappearing from the landscape of the Polish countryside.

This practice encourages the creation of new rituals. We gave some of the hay to animals after the exhibition in Tarnów, but we used some of it to create Christmas bunting for the gallery audience’s Christmas tables. We repeated this last year when you once again made hay works for us. Each bundle is accompanied by a photograph documenting the sculpture from which the hay came. A small but very beautiful custom of Christmas gifts for the public was created.

This idea was born thanks to you and perfectly sums up the ideas behind my work, that artistic gestures permeate everyday life in different, non-obvious ways, eventually becoming part of it. This year, you will also get hay. As far as I know, the package has already reached you — the only thing missing is the photo I have to choose. Maybe I will do it now because I know that our conversation is to be illustrated.

A lot of your work could be considered a kind of spatial poetry, but you also write. How do you treat the written word?

A photo alone is often not enough, and a solid background is needed to understand the intention of the creator. Text can explain this. It is perhaps the eternal dilemma of what is more important — the image, the sign, the symbol, some other pictorial form — or the word. What, for example, is better evidence/commentary: a photograph documenting a crime scene — what’s more, taken with a film camera — or the story of a witness. Besides, text stimulates the imagination in a different way, and although as a medium it is one of the most demanding, it is at the same time probably the most egalitarian means of expression — anyone who can read a language has a tool to explore it. In the near future, I would like to publish all my short stories and instructions for works or scenarios for walks. I think taking them out of the context of the visual arts will do them good. Writing characterises and complements what I do well.

In your work Difficult Terrain, you documented how you cut through dense blackthorn. Later you planted blackthorn bushes in your field.

This bush is very characteristic for the Tarnów area, and the town takes its name from it — if Jan Długosz is to be believed. These bushes usually grow on sunny slopes. On the one hand, they are very striking to the eye — especially around late April/early May when they bloom white — on the other they are hostile to humans, thorny, injurious and highly expansive. But the blackthorn’s root system ties up the soil, preventing it from sliding, and the thickets themselves make great hiding places for wild birds and animals. That is why, a few years ago, I decided to plant a thousand saplings of this shrub on my plot, making it unsuitable for humans in the long term and friendly to other species. I write about this in the story “The Field”, as it is precisely one of those works that elude photographic or film documentation.

This might be a good time to mention the art you make for other genres.

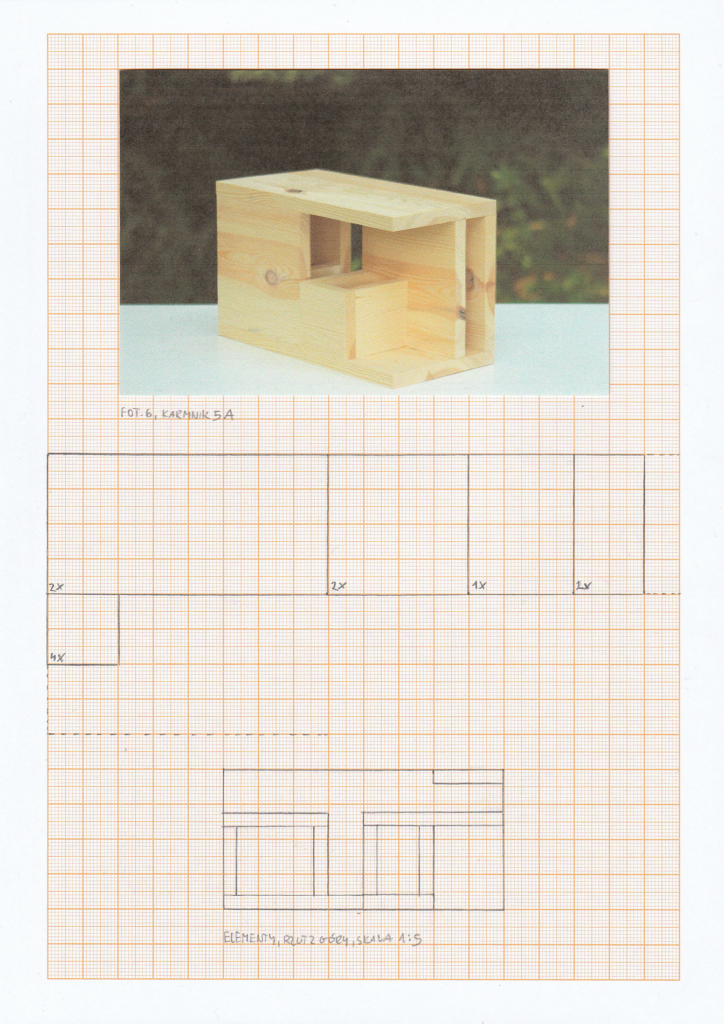

These are mainly sculptures-feeders for insects; trenches — I hope that in the future animals will make their own holes and burrows in them; feeders of very modern minimalist forms, which are in a way a formal experiment addressing the issue of whether contemporary ‘human’ aesthetics resulting from things like modernist traditions can satisfy the needs of birds; welded constructions for plants and snow, serving as ‘holders’ for branches, ‘shelves’, prostheses, etc.

In Tarnów’s Strzelce Park, you buried a tree trunk you bought from a sawmill, estimated to be around 80 years old. Monika Weychert wrote interestingly about this, comparing your gesture to a burial. On the one hand you have given the park’s soil new nourishment, on the other you have made a funereal gesture to honour and mourn nature that is dying before our eyes. Your actions and gestures are often placed precisely in the context of a climate catastrophe.

This is another work that we can include in the collection of those dedicated to other species — this time living underground. The theme you mention is important to me. My work can be traced back to earth art and conceptualism of the 1960s and 1970s, but what is important to me above all is the context of the spectre of climate catastrophe, of the irreversible damage to the planet’s ecosystem that we are currently witnessing. This is where my attitude comes from, as well as my vigilance and sensitivity to every little detail that is a representation of a bigger problem. Like the trunk you mentioned, which I gave to the earth in a mourning ritual. It is partly a synecdoche for the forest we are losing, which is why it has become such an important figure in this work. With the concept of synecdoche comes a change of scale — if we take care of our own backyard, others will do the same, as in a chain reaction. It may be a naive approach, but I believe that change must start with ourselves. I make material objects less and less, I don’t even really want to anymore. I am thinking of reducing my artistic activity even further to reduce my carbon footprint. I am annoyed by the cardboard boxes and bubble wrap in which the works going to the exhibition are packed. Therefore, I want to do only what is necessary, placing more emphasis on observation than on action itself.

We are talking about a change of scale. How do you see yourself and the perspective of a person’s lifetime?

The perspective and scale of humanity’s time on earth is very vividly depicted by the artist Ilana Halperin in the description of her work from the Nomadic Landmass (Pompeii of the North) series. In it, the artist mentions a volcano that emerged from an eruption on the Icelandic island of Heimay exactly in the year of her birth. She discovered this through an archival interview with Robert Smithson. Halperin established a relationship with this volcanic mountain, visiting it for while each year on her birthday, among other things. She knows that she will share her life with the volcano for a very short time. She writes of how the volcano will continue to exist after her death, and its age will move over time on a geological scale measured in hundreds of millions, if not billions, of years.

Some time ago, I calculated how much free time a person has, living on average 75 years.

Subtracting the time for sleep and regular work, this leaves about 350 thousand hours of free time, from birth to death. This year, at the exhibition at the BWA in Warsaw, I showed my most time- and labour-intensive work. The labour consisted of manual grinding of a nearly fifty-kilogram chunk of rock. I set myself the goal of getting to its middle and achieving a perfectly even surface. I used only files and collected the dust in jars. This work took me over 500 hours of strenuous effort, one of the greatest in my life — and I might add that working out at the gym was a breeze in comparison. I had to carve this time out from my daily routine, my work at the university, as well as other projects and responsibilities, which meant the process was spread over more than two years. After this time, I reached the inside of the chunk of rock, to the particles hidden inside it, millions of years old. I could smell them: dry, sweet, creamy. 500 hours is a lot. By my calculations, it’s 1/700th of the time we have to spend on our own in life.

What is art to you?

It may sound like a cliché, but it is something that will make the world a better place — not necessarily through art. Perhaps there will be a story to share.

Tarnów, October 2021

Ewa Łączyńska-Widz — art historian, curator, author of texts on art, director of the Biuro Wystaw Artystycznych in Tarnów. Together with Jadwiga Sawicka she curated the competition exhibition Views 2013. She is interested in combining contemporary art with local contexts. She lives in Tarnów, which is in the neighbourhood of Tuchów, where Krzysztof Maniak lives and works.